When Baseball Players Left it on the Field

At a very early age, our parents, teachers, and caregivers tell us to clean up after ourselves. Put away the toys, clear your dishes, throw away that dirty tissue because, no, mom and dad don’t want to touch your boogers either.

What’s good for preschoolers is good for baseball players, to the point where there’s even a rule about it. Major League Baseball’s rule number 3.10 states:

Members of the offensive team shall carry all gloves and other equipment off the field and to the dugout while their team is at bat. No equipment shall be left lying on the field, either in fair or foul territory.

Today, we take it for granted that, when you leave the field, your glove comes with you. But that wasn’t always the case — and wasn’t the norm, either. Before 1954, when that rule was added, it was customary for players to leave their gloves on the field — outfielders would drop them where they stood, shortstops and second basement would typically throw them onto the infield grass just off the dirt, and the first and third baseman would toss their gloves into foul territory. (The pitcher and catcher typically put their gloves on top of the dugout.) It’s unclear where the custom comes from or whether there was some superstition about bringing your glove into the dugout, but the tradition — for decades — was to leave the equipment behind.

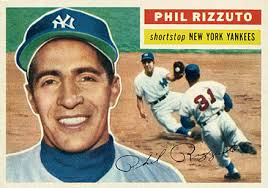

One thing is for sure, though: the habit of leaving your glove behind wasn’t all that convenient, in large part because opposing teams had few qualms screwing with each other’s gloves, even though retribution was easily achieved the next inning. Players would steal gloves or hide them, causing panicked fielders and delayed games. As an article from Sports Illustrated in 1984 recounts, “It became commonplace for players to stuff an opponent’s mitt with grass or sand or rocks” — and worse. The Sports Illustrated story further informs us that if “word got around that a certain player had a particular aversion to certain creatures,” that player “immediately became a target.” Famed Yankee manager Ralph Houk told SI that shortstop Phil Rizzuto was one of those targets: “they’d put dead mice in his glove—rats, frogs, lizards, all kinds of things. That really upset him.” (It probably upset the lizards, too.)

But rule 3.10 isn’t in place to stop practical jokers. What ultimately did the tradition in was how unsafe it is to have a foreign object on the baseball field, and how likely it was for an idly-lying glove to change the outcome of a game. You can pretty easily imagine a player trying to line up under a popup and instead tumbling over the opposing shortstop’s glove; that can lead to an injury and an error, both of which are best avoided. While the rule was a bit controversial when enacted — like many other rule changes, tradition weighed heavy — it gained acceptance shortly thereafter, and today, is taken for granted.

Bonus fact: Major League Baseball pitchers, per rule 3.01, can’t use foreign substances to “intentionally discolor or damage the ball.” The rule specifically references a few such substances — soil, sandpaper, emery paper, and. . . licorice. It’s not as absurd as it sounds — black licorice was once commonly used to mark up a ball, rendering it harder to see and therefore, harder to hit.

From the Archives: One Spud, You’re Out: The best trick play ever pulled in a professional baseball game.

Related: The rules of Major League Baseball, if you care to check my work. If not, black licorice.