A Berry Loopy Lawsuit

In 1963, the Quaker Oats Company introduced the world to Cap’n Crunch, a sugar cereal and its illustrated mascot of the same name. In development, it was a brand in search of a product. The Quaker team came up with the name and marketing plan, but nothing yet to put into the boxes they were ready to make. A researcher named Pam Lowe came up with the coating that gave these corn/oat puffs its enticing flavor, and the Quaker company liked it so much they gave it the Cap’n Crunch name they were so highly interested in. Quaker’s bet was that the public would like it, too.

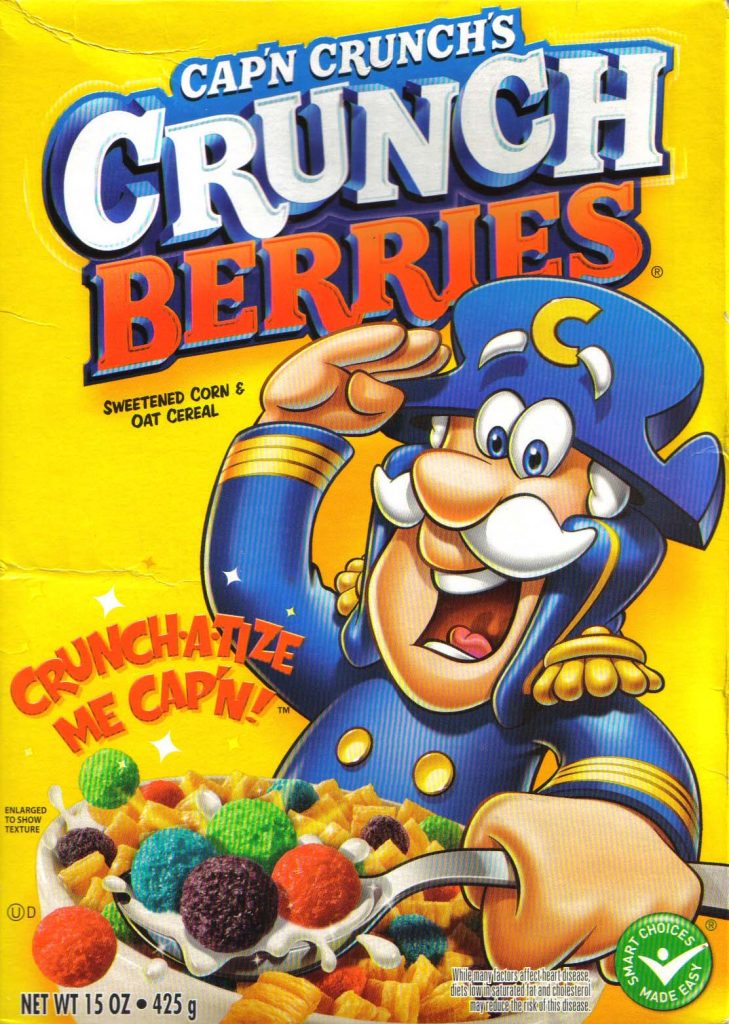

They were right. The product was so popular that it quickly rose toward the top of the charts, being outsold only by Tony the Tiger’s Frosted Flakes. Quaker had a winner on its hands, so they expanded. In 1967, they came out with Cap’n Crunch’s Crunchberries, as see below:

It’s the same thing, basically — flavor-coated corn/oat concoctions — but with color spheres in addition. The spheres, called Crunchberries, are vaguely, fruit-flavored — there’s some strawberry juice concentrate in there — but they most certainly do not grow on trees or vines. Crunchberries, like snozzberries, aren’t berries or fruits or anything like that. They’re just marketing fluff.

But not everyone was convinced.

In the summer of 2008, a plaintiff whose name is easily Google-able, but I’m omitting because her lawyer had a habit of sending nasty letters to publishers who discussed the lawsuit as it could embarrass her, filed a lawsuit. A California law disallows misleading advertising, and courts have interpreted the law to apply if “members of the public are likely to be deceived” by the ads (and “ads” includes cereal boxes). And the plaintiff, according to Lowering the Bar, claimed that “she was misled by the Crunchberries packaging, specifically (1) the word ‘berry’ in the name of the product, (2) the picture of ‘pieces of cereal in bright fruit colors, shaped to resemble berries,’ and (3) ‘the product’s namesake, ‘Cap’n Crunch,’ thrusting a spoonful of ‘Crunchberries’ at the prospective buyer.'” In other words: The lawsuit argued that the way PepsiCo (who by this time owned the Quaker Oats Company) marketed the cereal was deceptive; members of the public were likely to think that there was real fruit involved in its making.

In essence, she was arguing that crunchberries were a real fruit.

That’s how the court saw it, at least — and thankfully, she lost her case. The court ruled that it “is not aware of, nor has plaintiff alleged the existence of, any actual fruit referred to as a ‘crunchberry,’” and “so far as this court has been made aware, there is no such fruit growing in the wild or occurring naturally in any part of the world.” As such, the court dismissed the claim.

But before the court was done dispensing with the Case of the Fruitless Crunchberries, the judge noted that the attorneys representing this plaintiff weren’t new to cereal litigation. Previously, as another Lowering the Bar post notes, the firm had taken aim at Froot Loops, arguing that it, too, deceived purchasers into thinking it contained real fruit. That case, also, failed.

Bonus fact: Not all truth-in-advertising cereal lawsuits end up with a plaintiff being embarrassed by bad press. In some cases, the plaintiffs win. In 2009, Kellogg, makers of Rice Krispies, claimed that Rice Krispies “was fortified with nutrients and antioxidants to help support human immune systems,” according to Law360. No one would have likely cared about this claim, but it coincided with the 2009 swine flu (H1N1) pandemic, and many people were annoyed that Rice Krispies claimed to help kids and others fight disease during a period of panic. The Krispie claim wasn’t substantiated by any of the research, of course, so Kellogg lost the case. Kellogg agreed to pay $5 million in various penalties to settle lawsuits against it arising from their unwarranted claim.

From the Archives: The Curious History of Graham Crackers and Corn Flakes: They were created for reasons not listed on the packaging.

Related: Nordic Berries. They’re gummy vitamins and no, they aren’t real berries. But so far, they haven’t be sued for claiming otherwise.