A Star Spangled Snafu

On September 12, 1814, the United Kingdom began an invasion of the American city of Baltimore, Maryland. For the next four days, the two sides battled for control of the port city, with the Americans ultimately winning and forcing the British to withdraw. The Battle of Baltimore, as the event would later be known, isn’t much discussed in American history classes today, but almost every American knows the details of one part of the battle. On September 14th, an amateur poet named Francis Scott Key was present for the bombardment of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, and he wrote a poem recounting the defense of the fort. Today, his poem serves as the lyrics for the Star Spangled Banner, the national anthem of the United States.

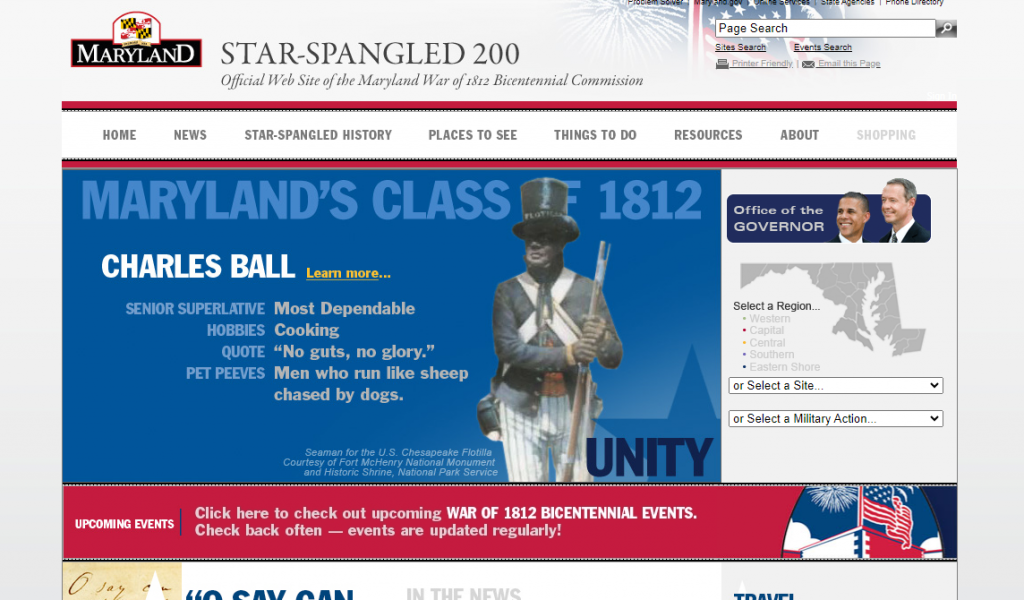

In June of 2010, Maryland decided to honor the bicentennial of the poem. In anticipation of that round-numbered anniversary, they issued the license plate above. The plate specifically mentions the War of 1812, shows a historically accurate flag over a building representing Fort McHenry, and bombs bursting in air. And there’s also a URL, pointing to www.StarSpangled200.org. It was, as you’d expect, an official website from the state of Maryland about the War of 1812 and the upcoming bicentennial, as archived here and seen below.

Maryland continued to issue the Star Spangled license plate through September 2016, and over the course of that six-plus year period, updated the website a few times (for example, here’s what it looked like in June 2016). But after the license plates were replaced by today’s version — something without reference to either the War of 1812 or the website — the website went away as well. As of 2019, as seen here, the National Park Service — that is, the Federal government — operated the website, redirecting the StarSpangled200.org URL to its page about the American flag during the war, Keys’ poem, and the origins of the United States’s national anthem.

But in February 2020, the National Park Service apparently failed to renew its ownership of that now redirecting URL. An unknown fan of the Star-Spangled Banner National Historic Trail — or maybe someone who figured out to make a quick buck off the domain name — set up a blog on that URL, as seen here. As a result, the roughly 800,000 drivers with Star Spangled plates were advertising the website, but no one seemed to care; while there wasn’t a lot of content on this new site, at least the site was pretending to be relevant.

That changed in late 2022. Someone else took over the URL that winter, and the new website, available here and as seen below, had nothing to do with America’s national anthem, or for that matter, America at all.

Yes, that’s an advertisement for a Philippines-based online casino — no stars, no banner, and definitely, not at all related to the War of 1812. And hundreds of thousands of Maryland license plates were, unintentionally, directing people to this website.

Apparently, those license plates weren’t the most effective way to spread awareness of the website because, even though the Philippines gambling ad was available through that URL as of late 2022, no one notable seemed to notice for months. In May of 2023, though, a Reddit member noticed the silliness and shared their discovery. News spread from there. On the last day of May, Vice wrote a story headlined “Maryland License Plates Now Inadvertently Advertising Filipino Online Casino,” in which the Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration (“MVA”) disavowed any connection to the then-active website (as if that needed to be pointed out).

Incredibly, the Maryland government resolved the problem in less than two weeks. On June 9, 2023, the Washington Post reported that, according to state officials, “the MVA engaged the services of a reputable domain broker and was able to successfully recover the URL.” As seen here, StarSpangled200.org now points to the MVA’s website.

Bonus fact: As noted above, the flag on Maryland’s Star Spangled license plates is historically accurate. If you look carefully, though, that flag has 15 stripes — two more than the current American flag’s design. That’s not a mistake. As the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian notes, the modern flag “has 13 stripes to represent the 13 original colonies.” But during the War of 1812, the flag had 15 stars and 15 stripes, each representing one of the then-15 American states. Per the museum elsewhere on its website, “It wasn’t until the Third Flag Act of 1818 that the country decided to stick with 13 stripes—one for each colony—and a star for each state.”

From the Archives: Star Spangled Ad Banner: How the American flag helped some Olympic athletes block a sponsorship message.