All’s Unfair

On February 5, 2012, the New York Giants and New England Patriots took to the gridiron in Super Bowl XLVI, a rematch of sorts from the big game contested just four years earlier. In one of the stranger plays in NFL history, the Giants took the lead, 21-17, with 57 seconds left in the game. The Patriots, then leading 17-15, realized that the Giants were almost certain to regain the lead (a field goal would have given the Giants an 18-17 lead) given that they had roughly a minute to score and were already on the Patriots’ six yard line. Wanting to preserve time on the clock, the Patriots engaged in a little bit of gamesmanship, and allowed Giants running back Ahmad Bradshaw to stumble into the end zone (despite his best efforts to fall down on the 1). The Giants took the lead, but the Patriots were going to receive the ball back with enough time to put up a meaningful drive of their own.

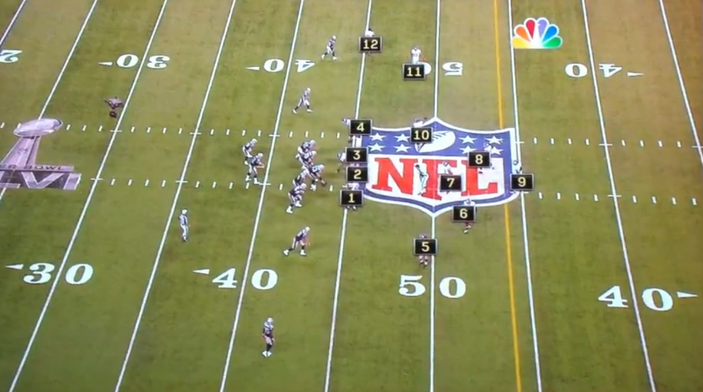

The Patriots started their drive on their own 20 yard line and, as seen above, they made it to their own 44 with 17 seconds left to play. Given the rules of the game, the Patriots had probably two plays left, and needed to get the ball into the end zone in order to win. Anything less would hand the Giants their second Super Bowl victory in five years. But something went wrong. The Giants had 12 players on the field, one more than is allowed. The play went on as usual, and the Patriots failed to connect on a pass, but the Giants’ infraction erased the play. Instead, the Patriots were awarded five yards, putting them on their own 49.

But this penalty came at a further cost — not for the Giants, but for the Patriots. The voided play took eight seconds off the game clock, leaving the Patriots with only nine remaining, and still needing a touchdown. Some wondered (example here) if the Giants did this on purpose — after all, having an extra man on the field would make it harder for the Patriots to score, and the five yard penalty was a more than fair price to pay to get the massive advantage from cutting the time remaining in the game in half. This turned out to not be the case. The extra player, labeled 12 above, was defensive end Justin Tuck, who was not only not the player you’d want on the field (you’d want a cornerback or a safety) but, more to the point, he was running off the field with his helmet off, hoping to exit the playing field before the Patriots snapped the ball.

Still, just because the Giants didn’t do this did not mean they couldn’t. What would prevent a team from intentionally breaking the rules in order to prevent an outcome demonstrably worse than the penalty they’d incur? The NFL has a rule, 12-3-3, which allows referees to award the other team a touchdown in order to account for actions which are “palpably unfair.” Thankfully, that’s rarely if ever been used in the NFL.

College football has a similar rule, and that one actually has been used — on New Year’s Day, 1954, in college football’s Cotton Bowl Classic. The Rice University Owls and Alabama Crimson Tide faced off and Alabama got on the scoreboard first when running back Tommy Lewis scored on a 2-yard touchdown run in the first quarter. (Alabama missed the extra point.) Rice’s own running back, Dicky Maegle, answered early in the second quarter, with a 79-yard touchdown run, giving Rice a 7-6 lead.

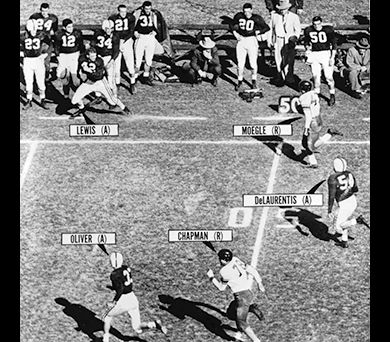

Maegle stuck again a few minutes later. He took off from his own five yard line and broke past the line of scrimmage, making his way down the right sideline. He had a mostly clear path to the end zone, and another seven points seemed inevitable, as seen above. But Lewis — on the sidelines, with his helmet off — took action. At around the Alabama 40 yard line, Lewis sprung from the sidelines and tackled Maegle, preventing him from scoring. Lewis’s gambit failed, however; the referees awarded Rice a touchdown.

As for Super Bowl XLVI? The Patriots failed to score on their final play and the Giants won, 21-17.

Bonus fact: The image above says Moegle, not Maegle, and it’s not a typographical error. Maegle was born Richard Lee Moegle, but his last name was pronounced in a way closer to “Maegle” than “Moegle,” and people kept mispronouncing it. He changed the spelling of his name to make it phonetically match the pronunciation.

From the Archives: Teddy Versus the Pigskin: How Theodore Roosevelt tried to take on another palpably unfair college football act.

Related: A handwritten note, to a fan, from Dicky Maegle, explaining that he changed the spelling of his last name when his children were born. The fan had sent Maegle a photo from a magazine and requested that the former college star (“Mr. Moegle”) sign it; Maegle, apparently, sent back a note correcting the fan’s error.