Before Jackie

For the almost the entire first half of the 20th century, African-Americans were barred from playing for Major League Baseball (MLB) teams. But on April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking the color barrier. Despite a lot of skepticism and hate, even from other players, Robinson was an immediate success on the field, winning the league’s Rookie of the Year honors that year. That success continued throughout his career: he took the league’s Most Valuable Player honors two years later, made the All-Star team six times, and in 1962, was enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1997, due to his contributions to the game — on and off the field — Major League Baseball retired his uniform number (42) league-wide.

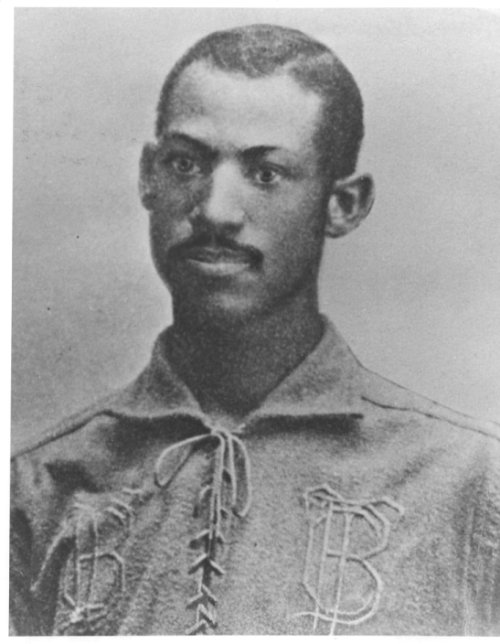

But he wasn’t Major League Baseball’s first African-American player. That distinction goes to a man named Moses Fleetwood (“Fleet”) Walker, pictured below.

Major League Baseball dates back to 1869, with the founding of the Cincinnati Red Stockings, the first pro baseball team. The two modern halves of MLB — the National League and American League — were founded, respectively, in 1876 and 1901. But there were some other leagues which, during the late 1800s, were considered part of the Majors. One of those, the American Association, existed from 1882 to 1891. When it folded, four of its teams joined the National League, and those four franchises are still around today. (In case you’re wondering, they’re the Reds, Cardinals, Dodgers, and Pirates.)

By modern standards, the American Association (AA) was hardly stable — teams joined and exited the league pretty regularly. One of those teams was Toledo Blue Stockings, which joined the AA in 1884, just a year after the team’s founding as a minor league squad. The Blue Stockings’ inaugural season in the AA wasn’t very good. They won just 46 of their 104 games and finished in eighth place. They were hit by so many injuries that at one point, the team hired the brother of one of its players to join their outfield. After the 1884 season, the team returned to the minors and, after that season, disbanded.

But for that one 1884 season, the Blue Stockings were a Major League team. And Fleet Walker was their catcher. He was, by some measures, an above-average hitter (for those who know what this means, his OPS+ was 107 — 100 is said to be “average”), and at least one of his teammates noted that he was a good defensive player. He was respected enough by some of his colleagues that his brother, Weldy Walker, was the outfielder hired mid-season to take over for one of the injured players; Weldy came to the plate 18 times over five games.

But Fleet Walker, despite his talent, had a hard time finding teams which would hire African-American ballplayers after that 1884 season. Many other players, including Hall of Famer Cap Anson, specifically refused to play with Walker; in 1883, when the Blue Stockings were still a minor league team, Anson threatened to sit out an exhibition game versus Toledo if Walker took the field, and only backed down after Walker’s manager threatened to withhold gate receipts if Anson skipped the game. Similarly, one of Walker’s Toledo teammates, despite thinking highly of Fleet as a player, reportedly didn’t like playing with him due to his race: “he was the best catcher I ever worked with,” said the teammate, “but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals.” Walker bounced around on various minor league rosters after 1885, and was out of baseball entirely after the 1888 season. According to a biography on the Society for American Baseball Researcher’s site, he ended up returning to Ohio after being acquitted of murder — in 1891, he killed a man during a racially-charged knife fight in Syracuse — and ran an opera house until his death in 1924.

By 1889, both the American Association and National League began excluding African-Americans as a matter of (unwritten) policy, which lasted until Robinson’s debut in the spring of 1947.

Bonus Fact: Before his baseball career, Jackie Robinson was in the U.S. military. In 1944, he was court-martialed for being insubordinate. Much like Rosa Parks more than a decade later, Robinson refused to move to the back of a bus and give up his seat to a white person. Even though the Army bus lines weren’t segregated, the bus driver demanded that Robinson move to the back of the bus so that a white person could take the closer-to-front seat Robinson was occupying. Robinson refused and the driver backed down, but before Robinson could disembark, the driver called military police. Robinson was charged with two counts of insubordination but was acquitted.

Take the Quiz!: Jackie Robinson — and for that matter, Fleet Walker — played their entire MLB careers for only one franchise. This quiz has 26 guys who did the same — all batters, ranked by number of plate appearances. Name them. (Caveat: this is as of 2011, when that quiz was written, and the asterisked player is very close to no longer qualifying.)

From the Archives: Swing and a Miss: The back story to baseball’s gender barrier. (And the title is one of my favorites.)

Related: “The Court Martial of Jackie Robinson” a made-for-TV movie from 1990 which, apparently, was pretty good.