Behold the Power of Dried Plums

“Say cheese.”

If you’re posing for a picture in an English-speaking area, you are very likely going to hear those two words. Outside of the deli counter, though, it’s rare that you’ll see any cheese in photographs, and in any event, people rarely say “cheese” as a stand-alone word in any other context. But there’s no secret as to why we do this when taking pictures: we want pictures our pictures to have big, toothy smiles, and the long E sound in the word forces our mouths to make a smile-like shape.

We didn’t always, say cheese, though. As recently as the 1950s, photographers had a different command: “say prunes.”

Why? Because they didn’t want you to smile.

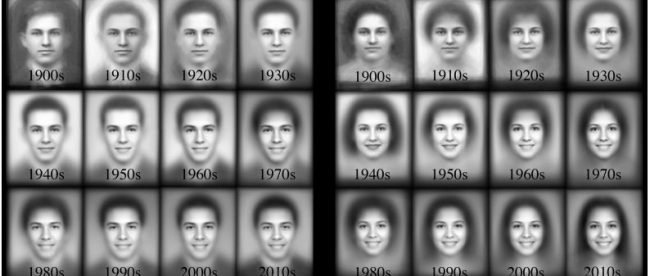

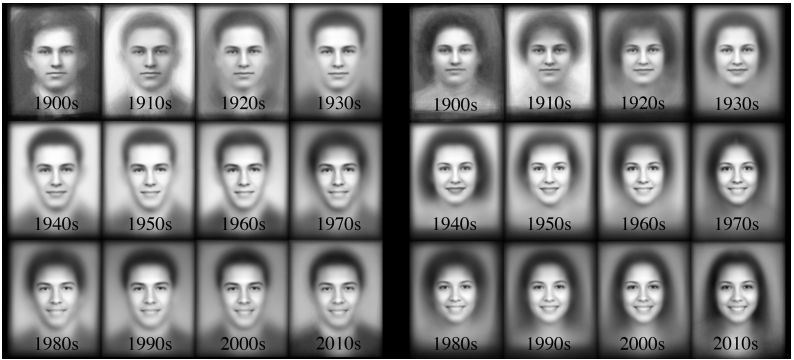

The image above (larger version here) comes from a 2015 paper titled “A Century of Portraits: A Visual Historical Record of American High School Yearbooks.” In the paper, according to TechXplore, researchers from the University of California Berkeley and Brown used “a dataset of 37,921 frontal-facing American high school yearbook photos” to create “average images of students by decade.” And as you can see, the modern “smile for the camera” edict only dates back to the 1960s or so, and as you go back further, the smile trend hasn’t yet emerged.

Were people more serious a century ago? Maybe, but that’s probably not why the average high school portrait from the early 1900s had such a stern face. More likely, technical limitations were responsible for precluding early smiles, and then cultural inertia took over. Or, as to the above-linked paper summarizes, “in the late 19th century people posing for photographs still followed the habits of painted portraiture subjects. These included keeping a serious expression since a smile was hard to maintain for as long as it took to paint a portrait.”

So instead of eliciting smiles, photographers from a century ago tried to get their subjects to show a stern seriousness. Prunes were an early solution. Like cheese today, the prunes weren’t eaten or, for that matter, even present. The mere utterance of the word did the job. The Washington Post reports that “shooting in the 1840s, British portrait photographer Richard Beard told his subjects to say ‘prunes’ as a cue to keep their mouths prim, according to historian Robert Leggat.”

The trend lasted more than a century; as recently as 1958, there are newspaper reports citing photographers’ use of the prune tactic. But ultimately, cheese — and smiles — won out.

Bonus fact: Prunes, as a food, are known for their laxative effect, which makes them a decent home remedy for certain ailments but hurt their marketability as a tasty snack. As the 20th century came to a close, the prune industry found that their sales were slumping, and many attributed the soft market to this stool-softening reputation. The solution? A prune business consortium asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration if they could label the products using a different name: “dried plums.” The FDA agreed, which makes sense — prunes, after all, really are just dried plums.

From the Archives: Why do our fingers prune up when they get wet?