D-Day’s Doomed Dry Run

On June 6, 1944 — D-Day — the fate of World War II hung in the balance as Allied forces attempted to liberate Nazi-occupied France. Over 150,000 troops crossed the English Channel that day, aboard nearly 7,000 ships supported by 12,000 planes, landing on a series of beaches in Normandy, France. By the end of August, there were more than three million Allied troops in France. D-Day and the larger Battle of Normandy was a decisive victory for the Allies and on August 25, 1944, the Germans surrendered control of Paris back to the French.

But D-Day almost never happened.

American General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the commander of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force and led the US and UK troops in northwest Europe. In this role, he assumed command of the planned D-Day invasion. And he wanted to do everything possible to make sure it would work. So he ordered a practice called Exercise Tiger. A beach in the south of Great Britain, then called Slapton (here is a map showing its approximate location) was to be the staging ground for a faux invasion, with the assault coming from across Lyme Bay directly to Slapton’s east. The roughly 3,000 people living in the area were evacuated and on the evening of April 26, 1944, Allied troops began their “assault” on the beach. It did not go so well.

The plan was to make the dry run “invasion” as realistic as possible, so gunships were to shell the test beach starting at 6:30 a.m. on the 27th for thirty minutes. At 7:30 a.m., landing ships would drop off the soldiers and tanks. At that point, the artillery would fire live ammunition well over the heads of the troops landing, much like they would be during an actual invasion. However, some of the landing ships were delayed, which in turn delayed the artillery fire. The battle cruiser received the orders to wait until 7:30, but some of the landing parties were not similarly instructed to wait until 8:30 to disembark. Some Marines lost their lives as they raided the beach at 7:30, just as the cruiser opened fire.

And then it got worse. The next day, nine German E-boats happened upon Lyme Bay. British sentries detected these enemy fast assault ships but opted to let them through rather than give away the location and size of Allied fortifications in the area. Instead, the British commanders radioed ahead to the HMS Azalea, a warship escorting a convoy of nine American LSTs (landing ships carrying tanks) through the bay. But the American and British forces were using different radio frequencies. The HMS Azalea believed that the LSTs knew about the E-boats, but they didn’t. The LSTs’ lone escort was insufficient to repel the attack and the LSTs were, colloquially, sitting ducks. Two of the nine LSTs were sunk and another two were damaged before the other LSTs could effectively return fire and force the E-boats to retreat. Many soldiers jumped into the water but put on their life jackets incorrectly, which as a result worked more like anchors than floatation devices. Decades later, Steve Sadlon, a radio operator from the first LST attacked, described the carnage to MSNBC. He jumped off his ship, aflame, into the English Channel. He spent four hours in the cold water until he was rescued, unconscious from hypothermia. His memories of the day are harrowing:

It was an inferno [. . .] The fire was circling the ship. It was terrible. Guys were burning to death and screaming. Even to this day I remember it. Every time I go to bed, it pops into my head. I can’t forget it. [. . .] Guys were grabbing hold of us and we had to fight them off. Guys were screaming, ‘Help, help, help’ and then you wouldn’t hear their voices anymore.

All told, nearly 1,000 men were killed. And beyond the cost of the lives lost, the death toll caused a massive strategic problem. The actual D-Day invasion was supposed to be a surprise, but mow, the military had to figure out how to keep the deaths of nearly 1,000 soldiers under wraps. This was done via threat of court-martial. Subordinate soldiers were informed that families were being told that the dead were simply missing in action, and any discussion of the tragic two days prior were patently disallowed. But even this was not enough. Ten of the men who went missing due to the E-boat attacks knew details of the D-Day invasion plans. Initially, Eisenhower and the rest of Allied leadership decided to delay the actual invasion, fearing that if any of those ten men were captured by the Germans, the enemy could have therefore obtained intel about the otherwise secret plan. Not until their bodies were discovered did the D-Day plan go back into action — with improved life jacket training and a singular radio frequency for both American and British forces. And unlike the dress rehearsal, the actual D-Day invasion, as we all know, was a success.

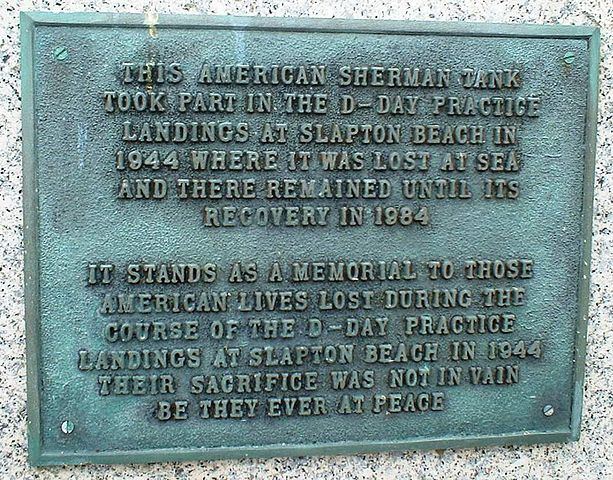

For decades after Exercise Tiger, the story went mostly untold. Before D-Day it was a secret; after D-Day it was old news. But in 1984, a resident of the Slapton Beach area managed to raise a sunken tank from Lyme Bay and turn it into a war memorial, pictured above with the plaque describing the tragedy.

Bonus fact: The only general to land at Normandy, by sea, with the first wave of troops was Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., the son of former president Teddy Roosevelt. He was also the only American to fight at Normandy alongside his son — Theodore Jr. was 56, and his fourth child, Quentin Roosevelt II (named after his late uncle), was a 24 year-old captain at the invasion.

From the Archives: The Phantom Menace: How the Allies used fake tanks and other such diversions to help win World War II. Also, Eisenhower had a speech written in case the D-Day invasion failed; here it is.

Take the Quiz: How well do you know your D-Day facts?

Related: “Exercise Tiger: The Dramatic True Story of a Hidden Tragedy of World War II” by Nigel Lewis (no relation). It’s out of print but used copies can be found for a few dollars. One review, five stars.

Leave a comment