Dueling Shields

In the late 1830s, Lincoln, then a member of the Whig Party, and Shields, a Democrat, were both members of the Illinois state legislature. While the two often did not see eye to eye politically, at times they were the key players in resolving inter-party differences and moving the state government forward. But whatever mutual admiration they had for one another waned shortly after Shields was named State Auditor.

In the early part of 1842, the state bank defaulted and the governor and treasurer wanted tax collectors to only accept gold and silver — and not paper money. Shields agreed, and, shortly thereafter, found himself mocked in the press. Seemingly random people were writing letters to the editor of a local paper criticizing Shields, with the first two — “Jeff” and “Rebecca” — calling him a fool and a liar but in relatively tame ways. Shortly thereafter, other letter writers under different pseudonyms aired their grievances with Shields in the paper, but this time with a much more hostile tone. Finally, Shields had enough and pressured the newspaper editor to reveal the true identities of the letter writers. The editor told him that “Jeff” and “Rebecca” were actually Abraham Lincoln, and Shields concluded that Lincoln wrote the other letters as well.

Shields wrote a note to Lincoln in response, one the Civil War Times called “menacing,” and demanded that Lincoln print a retraction. Lincoln took issue with Shields’ tone and refused, expecting Shields to reconsider his tone and then make the same request, but in a less threatening manner. Shields, though, was uninterested in tempering his words. Instead, he decided to escalate the matter. Shields challenged Lincoln to a duel, and given the culture of the times, Lincoln had no choice but to accept, even though the future President had no desire to actually fight Shields.

But as the challenger, Lincoln had the right to pick the terms of the duel. He proposed a curious and unique manner of battle: a clash of broad swords in a 12-foot deep pit, with two sides separated by a piece of plywood that neither combatant could cross. These rules were designed to make it all but certain that Lincoln would prevail, as Lincoln was at least a half-foot taller than his irate foe. Shields, nevertheless, accepted the terms. The two were scheduled to duel on September 22, 1842.

Before the duel began, Lincoln found a way to get Shields to back down. Lincoln cut down a tree branch above Shield’s head, demonstrating his height advantage and the certainty of his victory. Lincoln’s and Shield’s “seconds” — friends who could negotiate a truce on the behalf of the duelists — called off the duel. Not only was it going to be an unfair fight, but it turned out that Shields didn’t know the full story around the nasty letters in the newspaper; while Lincoln wrote the relatively tame letters from “Jeff” and “Rebecca,” he did not author the more insidious follow-up missives to which Shields took umbrage. (Those were written by two friends of Lincoln, one of which, Mary Todd, would become his wife just six weeks after the would-be duel.)

Lincoln and Shields reconciled soon after the non-duel. When the Civil War broke out two decades later, Shields served as a brigadier general for the Union Army, an appointment that had to be approved by the sitting President — Abraham Lincoln.

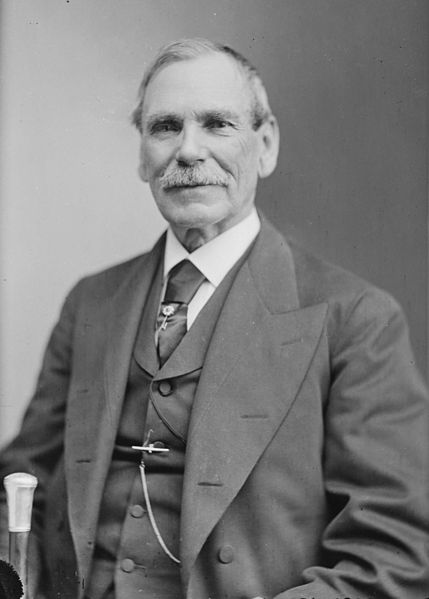

Bonus fact: Shields has another claim to fame: he is the only person in American history to serve as a United States Senator from three different states. He served a full term as one from Illinois, and, after failing to win re-election, moved to Minnesota, and became one of the first two Senators from that state. After the Civil War, he moved to Missouri (via Mexico and Wisconsin) and won a special election to replace a recently deceased Senator.

Double bonus!: Shields also is one of the few people to win a Senate election but then not be allowed to take office, at least not without winning again. Shields was elected to the Senate (from Illinois) in 1848, but that election was voided because Shield was ineligible for the seat. Born in Ireland, Shields became a U.S. citizen on October 21, 1840, and the Constitution requires that Senators be citizens for at least nine years. Shields didn’t take office and, in 1849, Illinois held a special election to fill the seat left vacant by Shields’ constitutional miscue. Shields, now eligible, ran again — and, again, won.

From the Archives: John Wilkes Booth’s Heroic Brother: Another odd tale from Lincoln’s life.

Related: “Speeches and Letters of Abraham Lincoln, 1832-1865,” free on Kindle. For those without a Kindle, there’s this hardcover book, but it only covers 1859-1865, and is $22 new (but $6 used). For everyone else, there’s an Abraham Lincoln Chia Pet.

Leave a comment