Everybody Was Kung Fu Panda Fighting

Pictured above is Po Ping, the protagonist character of DreamWorks Animation’s 2008 film “Kung Fu Panda. If you’re not familiar with the character, Po is, as the title suggests, a panda that knows kung fu. His back story is more complex, but you don’t really need to know anything about it for our purposes today — he could have been a karate chicken or a boxing buffalo, it really wouldn’t matter. What does matter is that the initial Kung Fu Panda movie was a smashing success, no pun intended. It brought in more than $600 million at the box office, and gave liftoff to an expansive franchise. To date, there have been two Kung Fu Panda sequel movies, each bringing in north of $500 million, with a fourth movie slated for March. And that’s just the theatrical part of the franchise. The Kung Fu Panda universe also includes three short films, three mutli-season animated TV shows, a holiday special, and five video games. Po is a billion-dollar bear.

Which may be why a guy named Jamye Gordon thought he could get $12 million off of Po.

The creators of successful fiction franchises often find themselves accused of plagiarism, for good reason and bad. First, most new creations are inspired by their predecessors; Star Wars, for example, has a lot of similarities to Dune (as outlined here). In turn, Harry Potter features an orphaned kid with magical powers who is sent to live with his aunt and uncle, in part to hide him from the bad guys; that could also be said for Luke Skywalker. No one would claim that Star Wars is a Dune ripoff or that Harry Potter is a Star Wars copy, though; inspiration isn’t imitation. And second, there’s the law of large numbers. With billions of people in the world, it’s unlikely that the people at DreamWorks were the first to come up with the idea of a panda trained in the martial arts.

But people get upset when they think big movie studios stole their ideas, and even if the studios did no such thing, you can’t blame artists for feeling victimized. Usually, lawyers for the studios will reply to such complaints with a quick note explaining that this was a coincidence or something to that effect, and move on. So when DreamWorks Animation found themselves being sued by the above-mentioned Jamye Gordon, a self-described artist, they probably were more annoyed than anything else. As the Hollywood Reporter explained in February of 2011, Gordon’s attorneys “filed a colorfully illustrated 28-page complaint [on his behalf] alleging that Dreamworks and distributor Paramount copied the film from Gordon’s copyrighted works, collectively titled ‘Kung Fu Panda Power.'” He was seeking $12 million in damages.

The two sides battled over the next two-plus years, but right before the case was supposed to go to trial, Gordon withdrew his complaint with prejudice — that’s a legal term meaning he also gave up the right to sue on the issue in the future. And in exchange, the Hollywood Reporter relayed in a follow-up story, Gordon received absolutely nothing. You don’t need to be a lawyer to know that’s rare. But Gordon’s case came with a major flaw: it was all a lie.

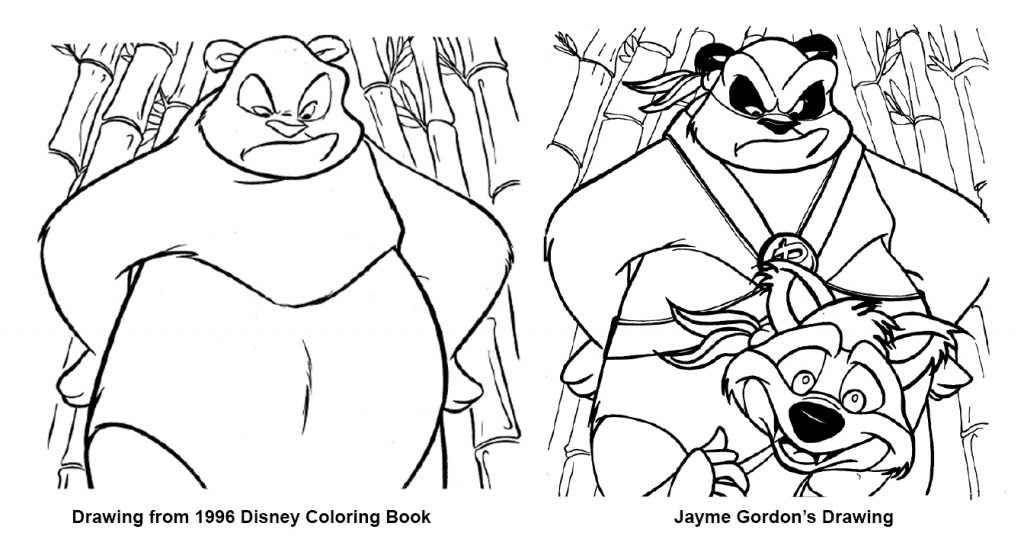

Part of the evidence that Gordon offered were sketches he made of a kung fu panda, dated 1992 or 1993. But during the course of discovery, DreamWorks’ lawyers found proof that the drawings weren’t from the early 1990s — or, for that matter, original works by Gordon at all. As seen below, via the FBI’s website (we’ll get to why in a moment!), the images were traced from a 1996 Lion King-themed coloring book published by Disney.

So, yeah, Gordon dropped his case. But the legal issues were just starting. DreamWorks had run up a $3 million legal bill fighting the suit, and they didn’t take kindly to Gordon’s claim. And neither did the Department of Justice, which prosecuted Gordon for wire fraud and perjury.

Gordon pled not guilty and went to trial. During the trial, according to the DOJ, ” Gordon testified that he had not traced his drawings from the coloring book. Instead, he claimed, Disney, like DreamWorks, had apparently copied his drawings and based characters in the Lion King on his work.” The government, per the FBI, offered evidence that was not true; on the contrary, “investigators learned that months before the release of Kung Fu Panda, Gordon saw a trailer for the movie. He had previously created drawings and a story about pandas—which he called ‘Panda Power’—that bore little resemblance to the movie characters. He proceeded to revise his ‘Panda Power’ drawings and story, and renamed it ‘Kung Fu Panda Power.’

The jury did not believe Gordon’s story and found him guilty. He was sentenced to two years in prison and had to repay $3 million in restitution.

Bonus fact: The success of the first Kung Fu Panda movie caused some consternation in China. As the Washington Post reported, the movie was “set in ancient China, highlights Chinese culture, mythology and architecture,” but wasn’t made in China — and many Chinese filmmakers weren’t happy about that. Their objection, though, wasn’t with the American studios that made the movie; it was with their own government. At the beginning of the movie, for example, Po is seen as lazy and uninspired, which isn’t a positive way to show a cultural icon like a panda. That would probably have been enough to doom the project, had it been produced in China. Per the Post, “many here [in China] blame a lack of imagination that comes as a result of tight government controls over the film industry and hypersensitivity over how China is portrayed to the outside world.”

From the Archives: Bearly Pregnant: The panda bear that lied about its pregnancy. (Probably.)