Floating Away On a Raft of Disappointment

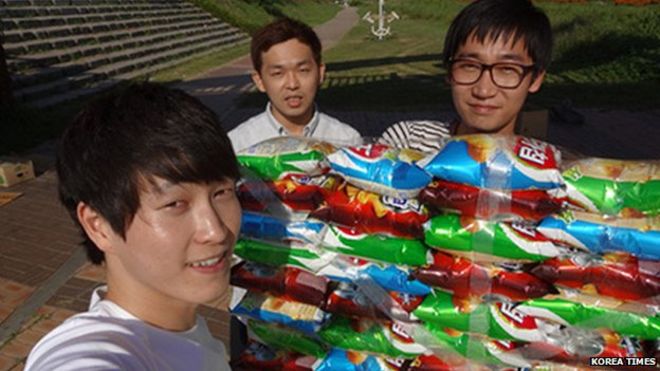

Pictured above is a pair of Korean college students rafting down the Han River, the major interior waterway in the nation. If you look carefully, you’ll see that the students not on a boat, though, or at least not a typical one. Here’s a view of them and a collaborator holding their seacraft.

If that looks more like a lot of taped-together potato chip bags than it does a boat, that’s because it is a lot of potato chip bags taped together — and it’s what they used as a raft. The students above are protesting against the amount of air in potato chip bags.

And it’s not as ridiculous as you think — because in Korea, snack food packaging is out of control.

Potato chips are packaged in air-filled bags by necessity — the air inside the bag acts as a cushion, keeping the chips from turning into crumbs, while also preserving their freshness. (The air is nitrogen, by the way; that’s something I discussed briefly in a bonus item, here.) But there’s an unspoken-of understanding between chip eaters and chip makers — we tolerate the somewhat-misleading volume of the package and they agree not to abuse the situation by over-inflating bags.

But in Korea, that agreement has broken down. Take a look at this bag of chips, below. It’s unconscionable.

Too few chips, too much space — and by a lot. And chips aren’t the end of the problem. Overpackaging has become a widespread problem in the world of Korean snack food, extending to cookies, brownies, and most everything else. Here is a gallery of some examples with the internal packaging discarded, showing the snacks relative to the amount of space in the otherwise empty box or bag. These “nitrogen snacks,” as they were often called, were out of control. There’s a law which requires containers to be at least 65% snack, but manufacturers have found lots of loopholes, resulting in the above.

And in 2014, some college students wanted to make a statement, which brings us back to the raft above. The Korean Times caught up with one of the students, who told the press that “we often feel ripped off when we find out how small the amounts are inside the inflated containers” — and this was their awareness campaign way of doing something about it. It worked, too; prompted by these students’ efforts, the Times interviewed a number of Koreans about the snack food packaging issue and found consensus across the board: it was a problem. One self-described housewife summarized the issue for the Times: “when I open a pack of snacks, I am often surprised to see only one third is filled with food,” while pointing out that “compared to imported products, Korean snack products have too much air and too few snacks.”

As for the raft itself, it worked, too, from a seafaring perspective. Gizmodo reported that the duo “were able to successfully navigate their vessel across the 0.8-mile width of the Han river in eastern Seoul, a testament to their boat-building prowess—and the relative emptiness of the snack bags they used.” And stunt certainly grabbed a lot of attention, getting press pickup from the BBC, the Wall Street Journal, and dozens of other outlets around the world.

But did it have an impact on the runaway packaging culture in the Korean world of snacks? Probably not. As cool as a raft of potato chips is, the profits from selling mostly-empty containers of snack foods is probably cooler. There hasn’t been much, if any, immediate change in Korean snack food packaging since the potato chip bag raft set out on its maiden voyage.

Bonus fact: Pringles are packed without a ton of air in their containers, and for that matter, aren’t packed in bags at all. But not all chips can be packaged that way. Pringles are special because they’re all the same shape and size, allowing them to be packed in a hard tube which requires no protective nitrogen bubble. How does this happen? Pringles aren’t sliced potatoes — they’re more like a weird science experiment. Here’s how io9 explains the process: “Instead of shaving bits off of a potato and deep frying them, the company starts with a slurry of rice, wheat, corn, and potato flakes and presses them into shape. So these potato chips aren’t really potato at all. The snack-dough is then rolled out like a sheet of ultra-thin cookie dough and cut into chip-cookies by a machine. The cut is complete enough that the chips are fully free of the extra dough, which is lifted away from the chips by a machine.”

From the Archives: Why Once You Pop, You Can’t Stop: Why you can’t stop eating potato chips once you start.