Frederick Douglass Is Not Amused

ictured above is Frederick Douglass, one of the most pivotal people in American history. Born a slave in Maryland, presumptively in February of 1818 (more on that later), Douglass managed to escape to the north in September of 1838. Within a decade, he became a prominent voice in the abolitionist movement. His 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, was a best-seller. Over the course of 11 chapters, Douglass detailed the experience of an American slave, putting to words the hell that generations of Black Americans were subject to. And perhaps more important than the historical record Douglass thereby provided, the book was evidence that ex-slaves were, in fact, capable of intellectual pursuits. His career as a persuasive orator further demonstrated this truth. To the millions of Americans of his time, Frederick Douglass was proof that slaves were, indeed, people.

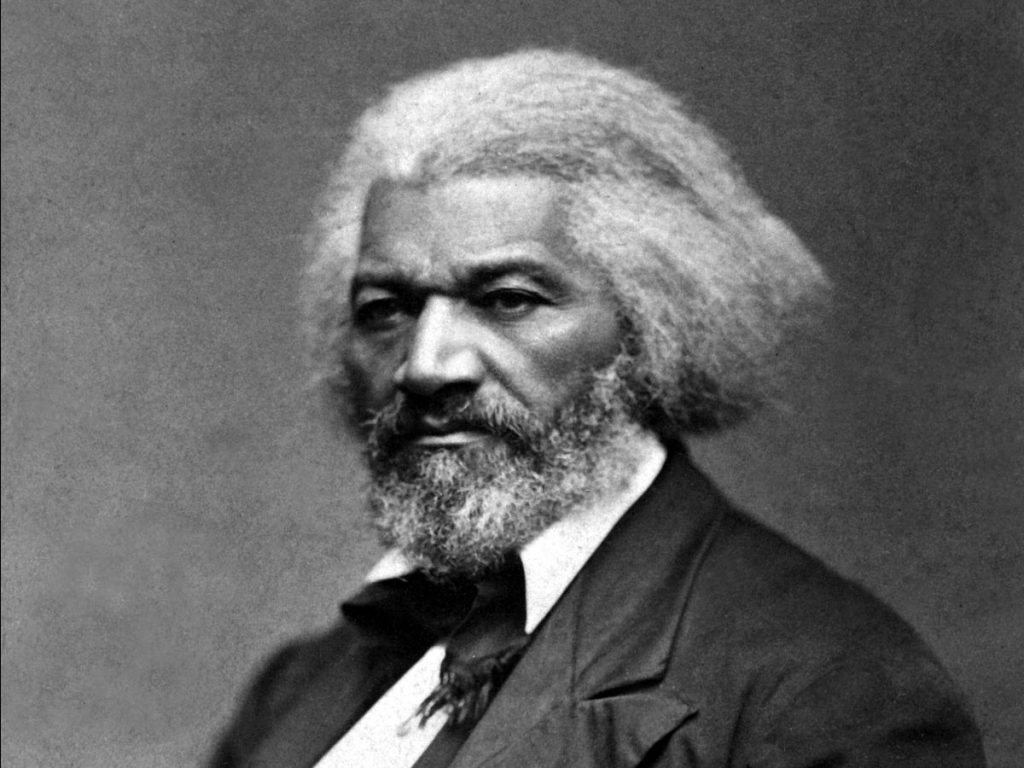

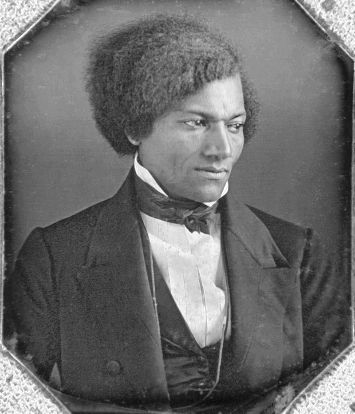

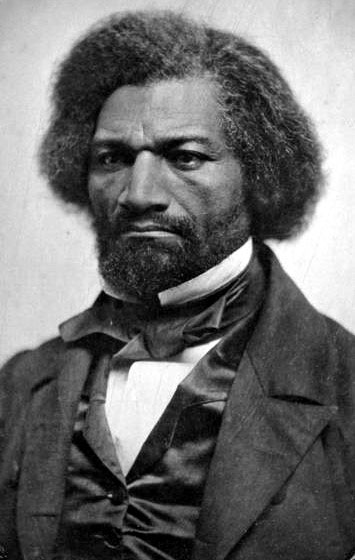

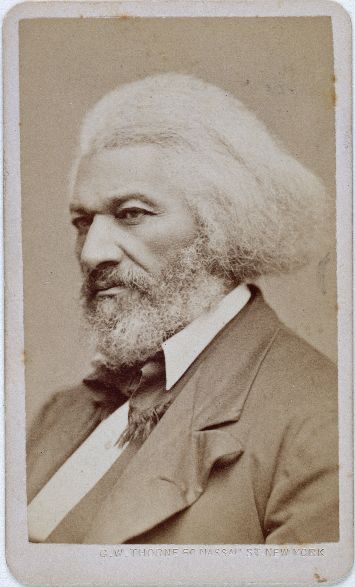

At around the same time, portrait photograph became increasingly common, especially for those people of public importance. And for Douglass, this became an opportunity. As Artsy notes, over the course of his life, Douglass sat for 160 portraits, a number high enough to “earn [him] the distinction of being the most photographed American of his time. Army officer George Custer came close with 155; Abraham Lincoln only made it to 126. Worldwide, only a handful of British celebrities and royals would top him.” Here are a few selections, from the 1840s, 1850s, and 1870s. (The image at the top is from around 1879.)

Four photos — here’s more if you need them — across almost forty years. And what you may notice is that Fredrick Douglass isn’t smiling in any of them.

That’s not an accident. While some of the early photos were daguerreotypes and had long exposure times, even then, smiling would have been an option, albeit a difficult thing to hold for so long. For Douglass, how he appeared was paramount to his effort to end slavery and racial discrimination. At the time, if there were images of Blacks in the newspapers, they were almost always cartoons or the like. And these illustrations were hardly positive or even fair representations of the people that they depicted. Rather, in the words of NBC News, Black men were often depicted as “laughable caricatures and menacing drawings,”

Douglass wanted to combat this — and photography was a way for him to do so. In a 2015 interview with NPR, John Stauffer, a professor of English and African-American Studies at Harvard, explained Douglass’s strategy in front of the lense:

It wasn’t necessarily a convention, but Douglass specifically – in print, he said that he did not want – he did not want to be portrayed as a happy slave. The smiling black was to play into the racist caricature. And his cause of ending slavery and ending racism had the gravity that required a stern look.

Coming off aloof, unserious, or even happy. could give the advocates of slavery and discrimination the wrong idea. So, he made sure to remain serious, almost never cracking even the faintest of grins. According to the Pocono Record, among those 160 photographs, there is only one — most likely this one, taken late in his life (1884) with his wife and sister-in-law — in which he smiled.

Bonus fact: Frederick Douglass celebrated his birthday on February 14th, which you probably immediately recognize as Valentine’s Day. That’s not a coincidence. Douglass never knew what his true birthday or age was — keeping accurate birth records for slaves wasn’t important to those who denied them basic human decency. Douglass adopted Valentine’s Day as his own birthday because his mother referred to him as her “Little Valentine.” His birthday and that of Abraham Lincoln’s (February 12th) led to the establishment of “Negro History Week” in 1926, which, starting in 1970, expanded into a February-long celebration of Black History Month in the United States.

From the Archives: The Slave Who Shipped Himself to Freedom: In a box. Literally.