Gutting One Out

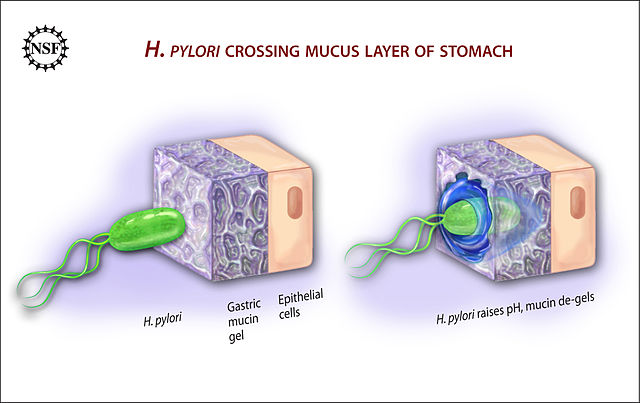

Peptic ulcers, which form in the stomach or opening to the small intestine called the duodenum, are most often caused by the bacteria Helicobacter pylori. H. pylori thrives in areas of high acidity, such as the stomach and duodenum. Some people can tolerate the presence of this type of bacteria in these areas are asymptomatic. But for others, the bacteria wins, creating a small breakage in the stomach or intestinal lining. Due in part to the highly acidic nature of these areas of our bodies, this ulcer can be particularly painful.

Proving it was painful, too.

In 1954, a doctor of gastroenterology named E.D. Palmer published a paper called “Investigation of the gastric mucosa spirochetes of the human,” which concluded that the human stomach contained no bacteria (spirochetes are a type of bacterium). Previous research, starting in the late 1870s, had been split on the issue. Some suggested that excess stomach acid caused the ulcers, while others believed that ulcers were caused by bacteria. But Palmer’s findings (which concluded that any bacteria found by other studies was the result of contamination) carried the day. Due to Palmer’s research, for decades, the medical community believed, collectively, that nothing could survive in the stomach’s acid. In 1957, for example, a pair of researchers concluded that antibiotics could help sufferers of peptic ulcers. But when the researchers presented their findings to the World Congress of Gastroenterology a year later, the other experts there, by and large, assumed that the findings were flawed — in large part because it conflicted with Palmer’s.

Around the same time, a Greek doctor named John Lykoudis developed a peptic ulcer of his own, and, skeptical of Palmer’s findings, treated it with antibiotics. It worked. Over the course of the next decade, he’d champion the cause any way he could. He obtained a patent for his treatment in 1960 and started giving it to patients. In 1962, he presented the treatment to a medical society in Greece. And a few years later, he submitted a manuscript about the treatment to the Journal of the American Medical Association. But all of those things were for naught. His presentation was not well received. The AMA Journal rejected the paper. And the Greek medical board fined him for his way of treating peptic ulcers — and Greek courts indicted him for a corresponding criminal act. (He was never incarcerated, though.)

In the early 1980s, two other researchers, Australians Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, took up the mantle left vacant by Lykoudis. But to get the attention — and, perhaps, the respect — of their fellow scientists, they needed to take bold action. The pair cultivated some colonies of H. pylori in Petri dishes for the better part of a week and then, Marshall drank a beaker full of the culture. Over the next few days, he developed gastritis, a condition which often leads to peptic ulcers. The pair tested Marshall to see if he had the bacteria in his system and, of course, he did. Soon after, Marshall took antibiotics — and of course, was cured.

Unlike Lykoudis’ work, Marshall’s and Warren’s was well received. In 1994, the U.S. National Institutes of Health concluded that “nearly all patients with duodenal ulcers have H. pylori gastritis” and “80 percent of patients with non-NSAID-induced gastric ulcers [that is, stomach ulcers which are not caused by too much stuff like Advil] are infected [with H. pylori.]” In 2005, Marshall and Warren were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their research.

Bonus fact: One side effect of the research into ulcers? Aspartame. The artificial sweetener used ubiquitously today was originally developed by a chemist looking to create an anti-ulcer medication. He accidentally spilled it on his hand, licked his finger, and realized that it was very sweet. It (probably) has no value to those suffering from ulcers, though.

From the Archives: Bacteriotherapy: A gross way bacteria can help cure things. Really, it’s gross — you may not want to click that.

Related: A plush Helicobacter pylori toy. Yes, you read that right.