Guest Post: How a Vice President Changed the English Language

This is a guest post by Liesl Johnson, as part of Now I Know’s Patreon program. For more information about the Patreon program and how you can support Now I Know, click here.

If you’ve ever wondered how many words are in the English language, only to Google it and find a baffling range of estimates, you can blame English’s constant state of flux. New words emerge; meanings morph. When the latter happens, there’s often a long, drawn-out battle between those who want to preserve the “right” meaning and those who want to go with the flow and let the words mean what the speaker intends, with plenty of vocal supporters on both sides.

Case in point: “literally,” whose newer meaning of “not literally” has been recognized by the Oxford English Dictionary since 2011 yet still regularly raises a ruckus. In cases like these, the sheer prevalence of a word’s new usage eventually overpowers the resistance, and the conflict fizzles out.

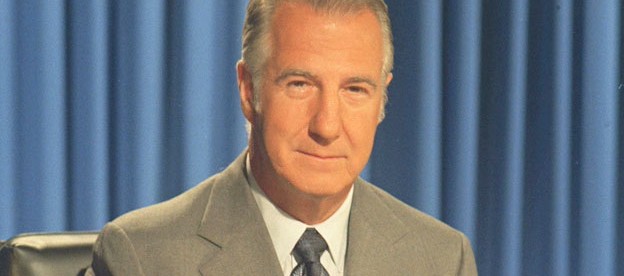

But here’s a story about a word whose meaning changed practically overnight, with little to no resistance, thanks to just one guy: Spiro Agnew, the Vietnam-era vice president to Richard Nixon.

Agnew always spoke in a low, sedate tone, according to Life Magazine, yet he had a real gift for zingers. (Or at least, he was great at delivering the ones prepared for him by talented speechwriters like William Safire.) On the receiving end of his ire were war protesters and the liberal media that supported them. Agnew accused these folks of “pusillanimous pussyfooting” and called them “nattering nabobs of negativism.” He even stated, in so many words, that liberal newspapers are only useful for birds to poop on. (Really.)

So as you can imagine, all this heavy-handed criticism really ruffled some feathers. If you happen to know people who spoke out against the Vietnam War, or people who supported the free press during that time, there’s a good chance they’re still feeling the burn from one particular comment Agnew made about them.

The word he wielded was “effete,” which means “worn out; ineffective.” Or at least it did until October of 1969, when Agnew publicly accused the anti-war media of being “an effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals.”

At the time, his statement met with applause from the likeminded audience he was addressing—some Republican fundraisers way down south— but for those receiving the vitriol, it really stung. It issued such a stentorian smackdown that it got lodged in the mind of the whole country. “Effete snobs” as a catchphrase almost instantly rose to YOLO-like heights of popularity. But there was a problem with it.

People incorrectly inferred the meaning of “effete” from the context of Agnew’s insult. They assumed, logically but erroneously, that “effete” meant “girly and weak” or “snobby,” so that’s how they started using the word themselves.

And of course, as the language expert Charles Elster has pointed out, it didn’t help matters any that “effete” kind of sounds like both “effeminate” and “elite”—the new, popular meanings.

To this day, when people say “effete,” odds are they mean “effeminate” or “snobby” rather than “worn out” or “ineffective.” For example, earlier this year, when Ian Buruma at The New Yorker described the “effete culture” of eleventh-century Japanese aristocracy, which placed value on poetry and perfumes, he definitely meant “effeminate,” not “worn out.” And when Brian Moylan at The Guardian mentioned the effete TV characters played by Kelsey Grammer, the meaning was clearly “snobby, intellectual, upper-class” and not “worn out.”

If there’s a lesson to be learned here, it’s probably not that we can make “fetch” happen if we roll it into a memorable insult but rather that the context surrounding a word can’t be depended on to make the correct meaning obvious. But let’s return to the alliteration-adoring Agnew: he ended up resigning from the vice presidency after being brought up for tax evasion. The Maryland Court of Appeals called him “morally obtuse”—a zinger that nobody misinterpreted.

This post was written by Liesl Johnson (M.Ed.), a word lover, learning enthusiast, and private tutor of reading and writing. She shares her zeal for vocabulary in a daily email called “Make Your Point.” Learn more at www.MakeYourPoint.us.