How to Claim Antarctica

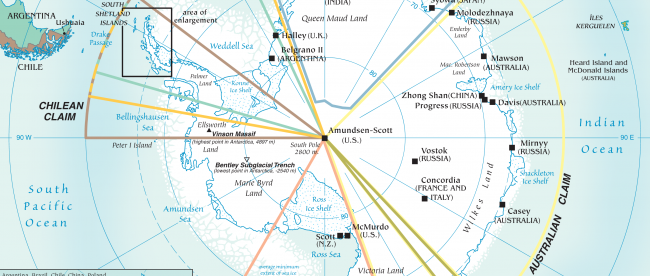

Antarctica is unlike any other place on Earth. You can’t grow much of anything there, it’s really cold, it’s not so easy to get to, the vast majority of it is covered in a mile-thick layer of ice, and no one lives there permanently. All told, it doesn’t have a government, per se, but it does have about 5,000 temporary residents and a lot of different research bases. In total, this makes Antarctica a complicated place, at least politically speaking. Here’s a map of all of the odd territorial claims, and while it’s a bit hard to read, that’s kind of the point. Antarctic governance is a mess.

You’ll note, though, that there are a lot of different nations making a lot of different claims. The basis for these claims are numerous and often in debate but, by and large, are symbolic anyway. Since 1959, there’s been an international treaty in place — the Antarctic Treaty System — which governs the icy landmass as far as the treaties’ 53 signatory nations are concerned. As are many international compacts, the details of the treaties are complicated, but here are two important ones: nations with pre-existing claims were allowed to assert them, and any signatory nation could set up a research base. Regarding that second point, take, for example, the Antarctic Peninsula, depicted in the inset above. Zooming in, we’ll see eight different bases in the region, run by five different nations (excluding those on King George Island):

That’s where we are now, at least, but even under the Treaty System, the early years of Antarctic governance were messy. Some of those nations grandfathered in under the Treaty still wanted to claim Antarctica for themselves, but there wasn’t a generally agreed-upon mechanism for determining sovereignty. As Colorado State University professor Adrian Howkins wrote in a doctoral dissertation on Antarctic claims (via Atlas Obscura), “all of the countries involved in the issue of Antarctic sovereignty are kind of making up the rules as they go along. In terms of international law, at that time and in the 1940s and ’50s, it was much more of an emotional argument than a legal argument.”

So countries got creative. And that creativity survived for a few more decades. So, let’s fast forward a bit — to 1977. At the time, Argentina took its territorial claims very seriously — it just needed a way to cement them.

Enter an Argentine woman named Silvia Morella de Palma. For her, the year 1977 was a special one — she was pregnant for most of it. And she was about to earn a free vacation. When she was seven months pregnant, the Argentinian government convinced her to be a pioneer of sorts — Argentina airlifted her to Esperanza Base in Antarctica. (It’s near the tip of the peninsula in the inset above.) And on January 7, 1978, her son, Emilio Palma, was born — the first child born on the continent.

The idea was straightforward (albeit weird): Young Emilio, by virtue of having two Argentine parents, was an Argentinian citizen. But, by virtue of his birth on Antarctic lands, he was a citizen of Antarctica — and the only citizen of Antarctica, for that matter. Emilio, a citizen of both lands, could then lay claim to his birth home for that of his parents.

Legally, the ploy didn’t matter much. The nations with the competing claims were under no obligation to recognize Emilio Palma’s claims, and of course, didn’t. But no one disputes that he was the first child born on mainland Antarctica — for a pretty odd reason.

Bonus fact: The United States doesn’t have a territorial claim on any part of Antarctica (despite having bases there), but under the Treaty System, it does have the right to make one later if it so desires. The basis for such a claim, though, won’t be related to Metallica — even though it could be, maybe. On December 8, 2013, the rock band became the first musical group to play a concert on all seven continents when it gave a concert to researchers stationed on Antarctica. (In case you were wondering: Denmark, by virtue of the fact that Metallica’s drummer Lars Ulrich was born there, can’t make a claim on Antarctica because Denmark isn’t one of the nations grandfathered into doing so under the Treaty System.)

From the Archives: The Queen of Suite 212: The baby born in the part of Yugoslavia formerly and currently known as London. (That’s not a typo.)

Related: Antarctica: A Year On Ice, a documentary on the few year-round residents of the last continent. 120 reviews averaging 4.6 stars.