How To Save a Sinking Church

Pictured above is Winchester Cathedral, a massive church in Winchester, England. (Here’s a map.) The cathedral was constructed over the course of five centuries — builders broke ground in the year 1079 and generations thereafter kept building expansions through 1532. It’s an incredible architectural site and if you want to visit, you won’t be alone; more than 350,000 tourists stop by each year.

But a bit more than a century ago, visiting Winchester Cathedral was a fool’s errand. It was, literally, falling apart. There were cracks developing in the walls, some sort large that owls could roost in them. Chunks of masonry were falling onto the floor. Some pillars were beginning to tilt inward. Something was wrong.

And the only person who could save it was the man pictured below, William Walker.

No, he’s not in some sort of Halloween costume. He’s wearing an early 20th-century diving suit.

It may seem odd that you’d need a diver to help repair a church; as you can plainly see in the image at the top, the cathedral is built on land and water. But in this case, the cathedral may as well have been built on a river, because it was built close enough to one for the waterway to have an impact. Not too far from the building is the River Itchen, and the groundwater system associated with that river runs right under the church. The soil beneath the church, as a result, is rather soggy and requires a solid, water-resistant foundation. And unfortunately for those of us who appreciate the architectural value of Medieval churches, the builders of a millennium ago used beech logs for that foundation. And, being made of wood, those logs began to rot over time. The church slowly began to sink into the ground below. It took a while, but by 1905, the building was in such bad shape that its administration feared collapse could be imminent.

The good news for fans of the cathedral was that the solution, in theory, was simple: replace the foundation with something more resilient. As Amusing Planet summarizes, “an architect Thomas Jackson and a civil engineer named Francis Fox were swiftly brought in. Fox and Jackson’s solution was to dig narrow trenches underneath the walls of the building, remove the decaying beech logs and fill them with concrete to firm up the foundations.” It was straightforward enough — until they put the plan into action. Amusing Planet continues: “when workers dug below the water table, the trenches filled up with water quickly and even a steam pump couldn’t hold it back long enough.”

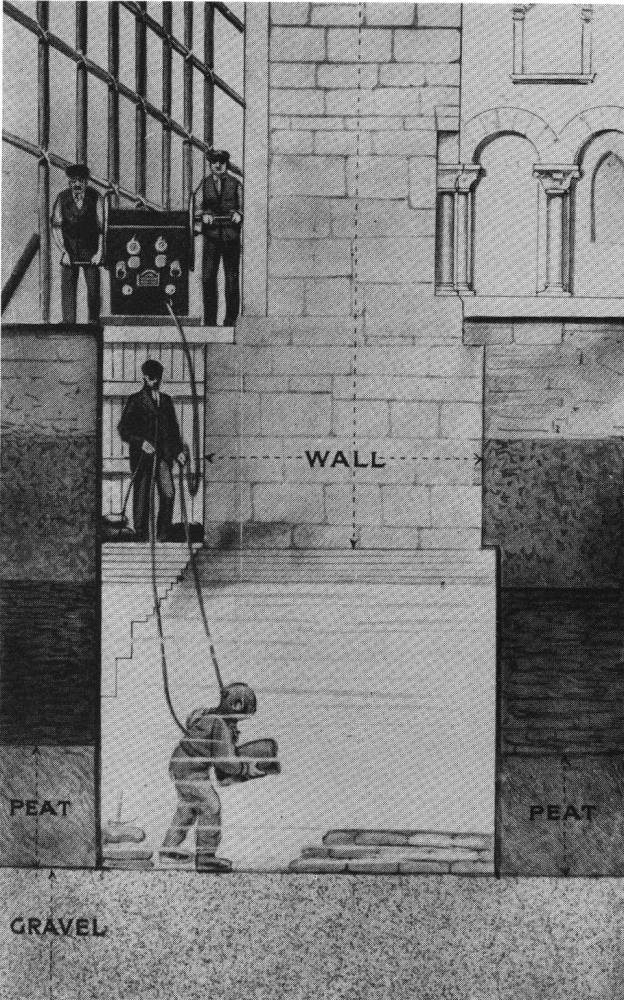

And that’s where William Walker comes in. Fox and Jackson hired Walker, a well-regarded Navy diver, to remove the logs and put in the concrete, as demonstrated by the illustration below.

The task was an arduous one. Per the BBC, Walker “worked in almost complete darkness in the peaty water 13 feet above his head which was filled with sediment.” The diving suit weighed 200 pounds — per another BBC report, “because it took him so long to put on and take off his heavy diving suit, when he stopped for a break he would just take off his helmet in order to eat his lunch and smoke his pipe.” And while the image above suggests that the amount of space that needed to be filled wasn’t enormous, it understates the task by a lot — builders dug 235 such trenches, and Walker filled all of them. In total, per the BBC, Walker installed “more than 25,000 bags of concrete, 115,000 concrete blocks, and 900,000 bricks.”

The process took six years.

Walker completed the job in 1911 but didn’t live much longer; his life was claimed by the Spanish Flu epidemic in 1918. Today, he is honored at the cathedral with a statue, seen here — which, like the cathedral itself — you can visit today, due to his efforts.

Bonus fact: The Spanish Flu didn’t originate in Spain, and the misattribution of the disease can be fairly blamed on World War I. Because of the war, most European nations were censoring news that could suggest that their citizens were in peril; these nations didn’t want other nations to sense potential weakness. Spain, though, was neutral in World War I and, as Wikipedia’s editors explain, were “unconcerned with appearances of combat readiness [ . . . ] so its newspapers freely reported epidemic effects, including King Alfonso XIII’s illness.” As only Spain reported on cases, Spanish citizens and those in neighboring countries alike thought that, at first, only Spain was impacted, suggesting — incorrectly — that the virus got its start there. (The actual origin of the disease is still debated today, but there’s no reason to think it started in Spain.)

From the Archives: Underwater Repair Men: When the pipes from a reservoir break, how do you fix them?