@Jaws

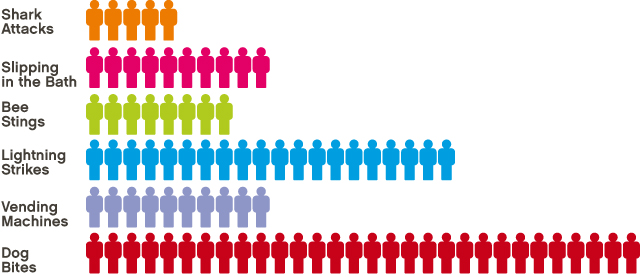

If you were to make a chart showing the relative likelihood of dying from a shark attack, it would look something like this:

The graph, via the Wake Project, tells a pretty clear story when it comes to human deaths attributable to person-eating sharks. Fatal shark attacks don’t happen very often, to say the least, but we tend to think otherwise — who among us is struck with overwhelming fear when buying a candy bar or a pack of gum from a vending machine? And besides, as another infographic demonstrates (click the link), people kill a lot more sharks than vice versa. But shark attacks do happen, and when they do, people tend to demand swift, decisive action.

Unless the sharks start tweeting. That is, unless they somehow start to use Twitter.

That’s what happened in Western Australia, at least. In November of 2012, a 35-year-old man was killed by a shark while surfing; he became the sixth person in the region fatally attacked by a shark since 2011. (Here’s an up-to-date tracker of such attacks, if you’re curious. There’s been an uptick this year.) At first, the authorities came up with a dramatically heavy-handed plan: kill a whole lot of sharks, specifically those “lingering near the southwest coast” per the Guardian. A dead shark, after all, isn’t all that likely to kill anyone.

There’s another way to prevent shark attacks, though — don’t let people swim or fish or otherwise go near the sharks. (Just to be on the safe side.) That was the method urged by environmental groups who believed that the “kill the sharks” strategy was misguided. The government agreed to explore alternatives, but to do that, you need surfers to know where the sharks are. The good news: Australian authorities had already accomplished about half that task. A government organization called the Fisheries Shark Response Unit had placed locator tags on 338 sharks by that point, so the sharks’ locations were already known — at least to officials.

The bad news? The Shark Response Unit needed a way to communicate the sharks’ whereabouts to the public, but building an alert system was expensive and unworkable. The work around was a Twitter account, as NPR explained. The Twitter account automatically published the location of a tagged shark once detected, as seen in the tweet below.

The program was expanded to include helicopters, which hover over the coast in search of untagged sharks. The location of those swimming dangers is also tweeted out.

While the “tweeting sharks” program may save a few human lives, it also has so far saved the lives of the tagged sharks, many of which would have been sentenced to death otherwise. And as a bonus, if you really need someone else to follow on Twitter, you can keep tabs on the sharks — even if you’re nowhere near Western Australia. Just follow @SLSWA.

As for vending machines? Just be careful out there — that menace is still left unaddressed. However, many of them tweet, too.

Bonus Fact: You wouldn’t surf there anyway, but it’s best to not dip into the waters between Baja California and Hawaii. This remote section of the Pacific is known colloquially as the “White Shark Cafe” because every winter and spring, a large number of great white sharks migrate there. As Wikipedia notes, no one knows why. The area doesn’t have a lot of food and there’s reason to believe the sharks do not use it as a mating area, either. To make the “Cafe” even stranger: while there, sharks have a habit of diving to depths of 1,000 feet as often as every ten minutes or so, and, again, we have no idea why. (It probably has nothing to do with Twitter and hopefully has nothing to do with vending machines.)

From the Archives: In Utero Fight Club: Sharks that fight — to the death! — before they’re born.

Related: A bag of sharks. Tweet-creating tagging system not included.