JFK and the Two Joe Russos

If you want to become a Member of Congress in the United States, chances are you need to first get lucky. Incumbent officeholders tend to get re-elected quite easily, particularly in districts where one of the major parties holds a big, built-in advantage. If the incumbent wishes to run again, you — the outsider — therefore doesn’t have much of a chance. And when the incumbent decided not to run for some reason, you need to get lucky, again; you’ll often need to get a plurality of the vote in a primary race with three or more candidates. If you fail to win, there may not be a second chance for a long, long time — the newly-elected person becomes the incumbent for the next election, and again, you’d find yourself running against someone with a perhaps insurmountable head start.

Which is why JFK’s dad probably paid a janitor to run for Congress.

In 1945, a Democrat named James Curley represented parts of Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the United States House of Representatives. But he wasn’t long for the job. Curley — a longstanding politician in the area — decided to run for Mayor of Boston, and he won rather easily. He took office in January of 1946 and, as a result, had to vacate his House seat. A number of local Democrats entered the primary hoping to be their party’s nominee for the House and, presumptively in a very Democratic-leaning district, the next House member from the area. The four favorites were Michael J. Neville, a Cambridge politician who would go on to be the mayor of that city; John Cotter, Curley’s campaign manager in the successful Boston mayorial campaign; Joe Russo, a city councilmember; and John F. Kennedy, the scion of a wealthy, politically-connected family and a decorated patrol torpedo boat commander during World War II.

Kennedy won, as you probably guessed, given that only 14 years later, he’d be elected the 35th President of the United States. But his election to the House in 1946 was hardly a lock. In a 1-versus-1 race against any of the other three major candidates, JFK was probably a clear favorite; by virtue of his familial connections, he was well-known throughout the Boston area and well-financed. But in a multi-way race, anything could happen. Neville was well-liked in Cambridge and Cotter could have ended up with the backing of Curley. But it was Russo that gave JFK’s father, Joseph Kennedy, the most pause. As Real Clear Politics notes, “There was only one Italian American on the ballot, Joseph Russo. The Kennedy circle believed Russo might win all of the district’s Italian American votes,” which — if Neville or Cotter could siphon enough votes for John, could give Russo the victory.

Russo, for his part, probably saw this as well. His campaign focused on Kennedy and his lack of qualifications — and Kennedy’s perceived effort to buy himself the election. According to the West End Museum (which focuses on the history of one of the relevant Boston neighborhoods), “Russo put an advertisement in the East Boston Leader that read, ‘Congress seat for sale. No experience necessary. Applicant must live in New York or Florida. Only millionaires need apply.'” It was somewhat unfair — Kennedy was a Bostonite — but instead of getting too involved in that debate, the Kennedy campaign tried a different tactic: they hired a janitor to clean up the mess. A janitor named Joseph Russo.

According to CommonWealth Magazine, he “scoured the Boston voter list until he found another Joseph M. Russo,” ultimately landing a Joe Russo who was more concerned with making ends meet sweeping floors than sweeping election victories. But the Kennedy family wasn’t looking for a favor; they were willing to pay. Per the West End Museum, the second Russo would later tell reporters that “’some wise guys’ asked him to enter the race in exchange for compensation, ‘they gave me favors. Whatever I wanted. I could of [sic] gone in the housing project if I wanted. If I wanted an apartment, I could have got the favor.'”

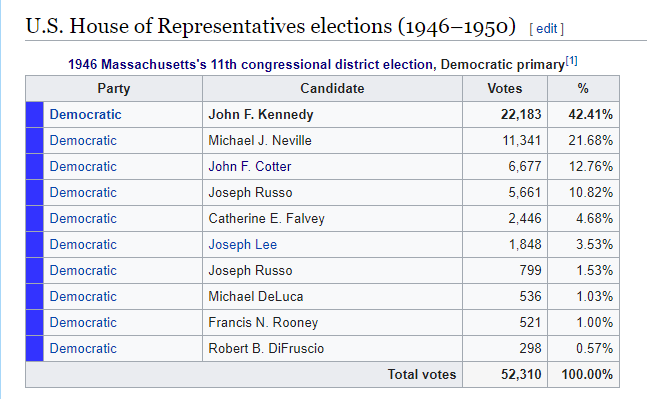

As a result, two Joseph Russos were on that Democratic primary ballot that year. The ploy turned out to be unnecessary — JFK won the election, as seen above, taking 42.4% of the vote to Neville’s 21.7. Cotter came in third with 12.8% and the two Russos had 18.8 and 1.5% respectively. Councilman Russo, for his part, decided to stay above the fray even after the election. After losing the primary, he immediately endorsed JFK for the House. Similarly, nearly two decades later, in an interview for the JFK Presidential Library in 1964, Russo was asked who he thought put the other Russo up for election. He stated simply “I’m not to say who put it in” and declined to blame the Kennedy family.

Bonus fact: James Curley’s term as Mayor of Boston in 1946 was its own adventure. About a year-and-a-half into his term, Curley was found guilty of mail fraud and sentenced to 6-18 months in a federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut; he ended up serving five months before President Truman commuted his sentence. But Curley didn’t resign as mayor upon his conviction; he simply took a leave of absence, and the City Clerk, John Hynes, was the acting mayor during Curley’s time behind bars. When Curley returned to Boston, he did so as mayor and claimed Hynes had done nothing, telling the press “I have accomplished more in one day than has been done in the five months of my absence.” Hynes, who was Curley’s political ally previously, took offense to the remark and ran against him for mayor in 1949 — and won.

From the Archives: Blame Cuba: How JFK stopped a crazy Cold War plan.