Please Be Quiet, We Can’t Hear the Martians

Today, the news cycle never ends. Websites, cable news, social media and the like — the world never sleeps, and we rarely unplug. It’s nearly impossible to imagine a world where that wasn’t true. But a century ago, that wasn’t the case. Newspapers typically came only once or twice a day, a nightly TV news broadcast was still decades away, and computers? Forget it. Radio dominated the news industry around the clock.

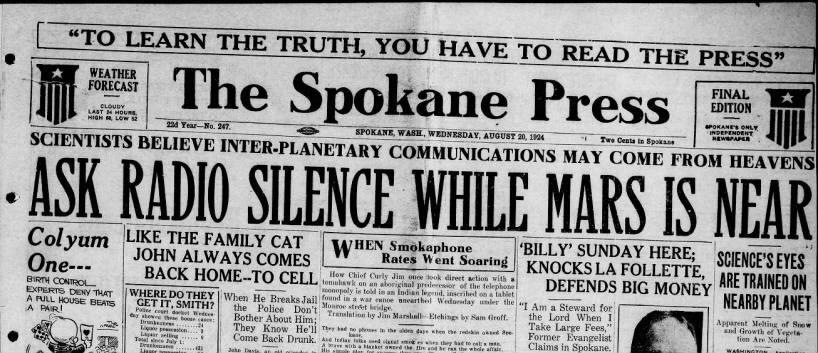

Except for 36 hours from August 21 through August 23, 1924. On that day an a half radio stations across the United States went silent for five minutes every hour.

Why? Because some scientists thought that radio signals would interfere with our ability to hear from little green spacemen.

From the end of the 1800s through most of the first half of the 20th century, many Americans were fascinated by the idea of life on Mars. (Atlas Obscura has a deep dive into the subject, if you’re interested.) The idea of intelligent life outside of Earth captured the public’s attention.

And for those interested in that potential, August 22, 1924 was a magical date — Mars was only 55.78 million kilometers (34.66 million miles) from Earth. It was the first time that the Earth and Mars were that close since 1845, and it would be the last time the two planets were so nearby until 2003. (If you’re curious, we’ll be roughly that close to Mars on August 14-15, 2050, so set your calendars now.) And while that’s not a reason for a momentous occasion today, at the time, it brought hope of contact from another world — assuming, that is, if we were listening.

In preparation for the Mars flyby, David Todd, a professor and the chair of the Amherst College astronomy department, started a public campaign to help us listen for sounds from the great beyond. The prevailing theory at the time was that our best hope of hearing Martian sounds was to pick up radio signals, and if that were the case — and we had radios tuned in to the right frequency — we could hear them. But, Todd observed, there was a problem. Our own radio stations could interfere with sounds from Mars.

So Todd began a campaign to get radio stations to stop broadcasting for a few minutes every hour while Mars was near the Earth — and he mostly succeeded. As seen above, newspapers nationwide put out the word asking broadcasters to get on board, and while there aren’t accessible records about whether radio stations complied, it’s generally believed that many did. The airwaves were clear in case aliens wanted to phone home (or, I guess, phone us).

The American military took up the mantle to listen for that call. Admiral Edward W. Eberle, then the Chief of Naval Operations for the United States, issued a memo to all Navy monitoring stations, asking them to “note and report any electrical phenomenon [of] unusual character” and to monitor “as [many] wide band frequencies as possible” during the period. The United States Naval Observatory also hoisted a special radio receiver about 8-10 km (5-6 miles) toward the sky in hopes of getting a clear signal.

But alas, no Martian music was detected that day or since. A century later, there’s little reason to think there ever will be.

Bonus fact: The most famous fictional Martian is probably Marvin the Martian from Looney Tunes, but that almost wasn’t the case. Spock, from Star Trek, almost came from there, too. Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek, “conceived [Spock] as a red-hued Martian” according to the book “Star Trek Creator: The Authorized Biography of Gene Roddenberry,” but he ultimately thought better of it — because he had hoped Star Trek would lead to more space exploration, and, perhaps, the discovery of life on Mars. The book continues: “Gene decided that if the show were a success, explores might actually land on Mars during its run, so Spock’s origin was moved to another, un-named planet.”

From the Archives: The Last Exit on the Information Superhighway: The place where there’s no radio.