Do Cheering Fans Help Us Do Better? Let’s Ask Some Roaches

Imagine a world-class sprinter running in an empty stadium with nothing but the cameras quietly broadcasting his dash down the track. Now, imagine the same sprinter, but this time with a roaring crowd and seven other competitors. If your gut tells you that the sprinter is going to perform better in the latter situation, you’re probably right. In the 1890s, Norman Triplett, a professor of psychology at Indiana University, ran a series of experiments (summarized here) to test the theory. He found that when we’re alone in such situations, we don’t perform as well as we do when we’re with other competitors or spectators — a theory later coined as “social facilitation.”

But let’s take a look at a second situation — one overused in action movies. With just seconds to go, an explosive device is about to go off and an amateur bomb squad-wannabe has to figure out the intricate systems of wires and fuses before it’s too late. In this case, a cheering audience is probably not a useful addition, but rather an unwelcome distraction. We’ve all experienced something similar — that uneasy feeling when you’re doing something complicated with someone hovering over your shoulder. Social facilitation? Hardly — more likely than not, the spectator is making things more difficult.

Sometimes, an audience makes us better — but othertimes, not so much. What gives? The science community is confident it has an answer, but only due to the hard work of a lot of cockroaches.

Yes, cockroaches.

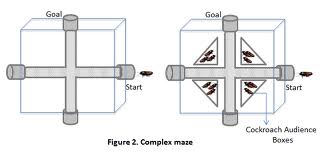

In 1969, University of Michigan professor named Robert Zajonc wondered about this disconnect in the social facilitation space — and had a fascination with cockroaches, too. As explained in the book “Invisible Influence” by Jonah Berger, Zajonc set up a stadium of sorts for cockroach maze runners with room for some cockroach-fans to watch. The field of competition, per Berger, featured “a large Plexiglass cube.” One side had “a small, dark starting box where the cockroach waited for the race to start, separated from the track by a thin metal door. On another side of the cube was the finish -line, another small, dark box separated from the track by a similar metal door.” But the cockroach-racers weren’t alone. Again, per Berger, “Zajonc also built cockroach stands next to the track [with] a clear wall separat[ing] them from the racetrack.”

Zajonc then had the cockroaches run in a straight line through the cube. (Cockroaches, Berger explains, hate light; Zajonc turned on a floodlight behind the roaches and which in turn scurried for safety.) Some of the trials featured the racers alone, other races came with a full house in the stands. In the experiments with “fans,” the roaches moved faster.

Then, Zajonc tried a second set of experiments — another race, but this time, the cockroaches had to turn right or left (it varied) in order to get to safety. (Here’s a small diagram.) This time, the fans had a negative effect on cockroach performance — “the audience led the roaches to run slower, increasing their time by almost a third,” per Berger.

Zajonc concluded that the easier, almost reflexive tasks were facilitated by having a crowd, but complex ones — which require thought and care — were made more difficult by the audience. And if that sounds like something true for us humans, too, that’s because it probably is.

Bonus fact: Cockroaches are even more social that the above story notes. In 2006, a professor named José Halloy demonstrated that groups of cockroaches can work together to make collective decisions. The roaches, through what Halloy deemed “chemical and tactile communication” (cockroaches don’t speak), were able to coordinate. Discovery News provided one specific example: “if 50 insects were placed in a dish with three shelters, each with a capacity for 40 bugs, 25 roaches huddled together in the first shelter, 25 gathered in the second shelter, and the third was left vacant

From the Archives: RoboRoach: How technology turns cockroaches’ socialization into a weapon against them.

Related: “Invisible Influences: The Hidden Forces that Shape Behavior:” by Jonah Berger. 4.2 stars on 49 reviews.