Stealing Back the Stone of Destiny

For centuries, Scottish monarchs were crowned while sitting or standing on a large, rectangular slab of red sandstone kept in (the long gone) Scone Abbey near Perth. The stone, called the Stone of Scone or the Stone of Destiny, is legendary. As with most legends, many parts of its early history are probably fictional. But the importance it plays in Scottish history and lore is undisputed. It is a national symbol dating back over a millenium.

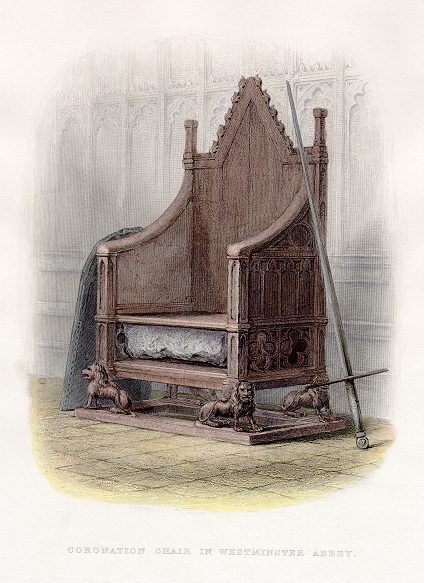

The fact that, for centuries, it was not in Scotland, is also mostly agreed upon. In 1296, English King Edward I invaded Scotland in the Battle of Dunbar and, as a spoil of war, took the stone with him back to London. Upon his return, he ordered the commission of King Edward’s Chair, pictured above (and also known as the Coronation Chair), which contained a slot specifically created to house the stone. The chair, which has been used for coronations since, was designed to send a not-so-subtle messaged that Edward hereafter ruled over Scotland.

As one could imagine, Scottish nationalists since have wanted the stone returned.

In 1328, the Scots almost got their way. England and Scotland entered into a peace treaty — the Treaty of Northampton — in 1328, and one of the terms in a concurrent agreement had England returning the stone. But due to unruly crowds, the stone could not be removed from Westminster Abbey safely. And it would sit there for another six hundred years, until Christmas Day, 1950.

Sometime that day, four Scottish nationals — all students — surreptitiously made their way to the Coronation Chair and managed to remove the stone while avoiding detection. They did so successfully but with one casualty: the stone itself. During the transport out of the Abbey, the stone broke into two pieces, one much larger than the other. Nevertheless, the quartet — now aided by an Englishman (who happened to be a direct descendant of Edward I) who supported the Scottish Nationalism movement — made their escape, the two pieces of the Stone in tow. They returned it, broken, to Glasgow.

Back in Scotland, a stonemason repaired the damage. The stone’s caretakers hid it from British officials who ordered a search and recapture of it. Believing that obtaining a prolonged hiding place would be difficult, its possessors left the stone at Arbroath Abbey, entrusted with the Church of Scotland to keep it from the Crown. But on April 11, 1951, the Church gave it up. British authorities took possession of the stone and returned it to Westminster.

But the students’ efforts were not a total loss. In 1996, Parliament decided to return the stone to Scotland, with one condition — it is to return to Westminster for coronations. Today, the stone is on display at Edinburgh Castle alongside the Scottish Crown Jewels.

Bonus fact: One of the students involved in the Christmas Day stone heist was Ian Hamilton, who three years later, would go on to become a lawyer. In 1953, he sat for admission to the bar, but when asked to swear his allegiance to Queen Elizabeth II, refused. Hamilton’s objection was that Queen Elizabeth I reigned in the late 1500s (and briefly into the early 1600s), before Scotland was part of the (present-day) United Kingdom — and therefore, he could only swear allegiance to “Queen Elizabeth,” without the regnal numbers after her name. He ended up bringing suit to defend that “right” and, as one would expect, lost. The Scottish court ruled that the monarch has the prerogative to choose his or her own name.

From the Archives: Representation Without Taxation: How a weird curiosity of law gives Scotland a bit of power over England. Also, Wine and Cheese with the Queen: The story of a guy who broke into Buckingham Palace to grab a snack with Queen Elizabeth II — twice.

Related: Stone of Destiny, a movie about the Stone. 27 reviews, 4.5 stars.

Leave a comment