The $2.56 Trophy

If you work or dabble in programming languages, there’s a good chance you know the name Donald Knuth. He earned his PhD in mathematics from Cal Tech in 1963, but pivotally took a side gig as a student a year prior, accepting an invitation to write a book about computer programming language compilers. (If you don’t know what that means, don’t worry — it’s not important for our purposes today). He realized he couldn’t do that book justice. Computer programming was very, very new at the time and no one had put together a resource that outlined the landscape of that endeavor. So Knuth took it upon himself to do just that. He published the first seminal treatise volume, “The Art of Computer Programming,” in 1968 — and he’s been revising and adding to it ever since. He made a name for himself along the way — he’s widely considered a leading expert in his field.

Of course, he made a lot of mistakes, too. And his biggest fans couldn’t be happier, because he pays them for finding them. But most don’t accept his money.

Writing books can be a perilous task. No matter how hard you and your editors try, mistakes happen. Sometimes a typo slips through. Other times, a fact that isn’t a fact gets passed off as one. (As far as I know, none of my books suffer from that second problem, but alas, I am aware of at least one typo that made it to print.) And even if you’re perfect, paper-and-ink is permanent, but times change, and sometimes, what was true when the books went to print is no longer accurate.

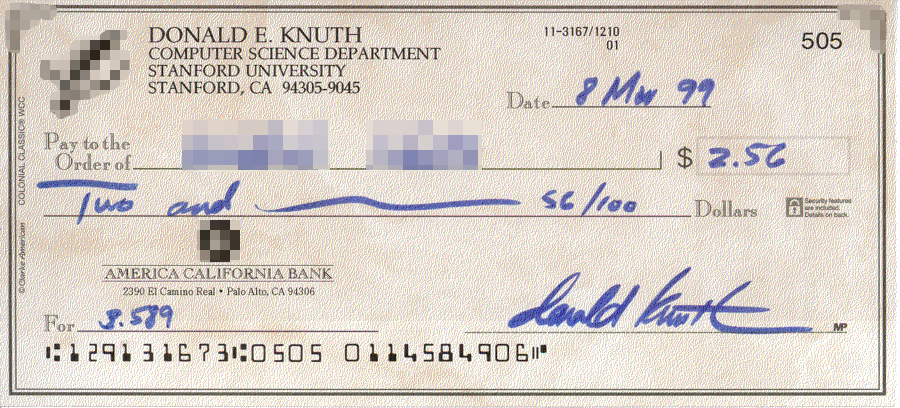

For most authors, this isn’t a huge problem — few get second or third print runs, and even fewer have multiple editions of their work published over the years. But for Knuth, the Art of Computer Programming is constantly being revised. (Its Wikipedia entry states that “the book is still incomplete” despite running more than 3,000 pages.) In order to make his books as accurate as possible, he offered a bounty for every mistake found — one hexadecimal dollar, or, in the base-10 world we’re all familiar with, $2.56. And, as promised, he sent people checks like the one below (via Wikipedia).

As he told a publication of the American Mathematical Society in 2002 (pdf), “There’s one man who lives near Frankfurt who would probably have more than $1,000 if he cashed all the checks I’ve sent him. There’s a man in Los Gatos, California, whom I’ve never met, who cashes a check for $2.56 about once a month, and that’s been going on for some years now. Altogether I’ve written more than 2,000 checks over the years, and the average amount exceeds $8.00 per check.” But Knuth wasn’t out $16,000 and change — far from it. It turns out that most of the check recipients are like the Frankfurt fan. In 2008, he noted in a blog post that “it turns out that only 9 of the first 275 checks that I’ve sent out since the beginning of 2006 have actually been cashed” (and jokes that “the others have apparently been cached). The checks are valued as collectors items well in excess of their ten quarters, nickel, and a penny face value.

Unfortunately, in that 2008 blog post, Knuth announced that the bounty program was coming to an end — kind of. As he noted in the above-linked blog post, sending checks to strangers (who put those checks on display) opened him to identity theft — his name, address, back account number, and routing number are all on those checks. (The one above is an old check, not reflective of his current information.) Instead, he started issuing fake checks from a fake financial institution, the Bank of San Serriffe, as seen here. (The location is a reference to an April Fools prank by The Guardian from 1977.) The end result was, roughly, the same: fans are still eager to get the collectible (fake) checks — and share such victories online regularly. And while you can’t cash those checks, if you really want the $2.56, don’t worry: Knuth noted that “I shall do my best to find a suitable way to send money to anyone who really prefers legal tender.”

Bonus fact: If you’re in the United States and need to pay your taxes by check, you probably won’t have an issue — unless you owe a huge amount of money. According to IRS Form 1040-ES (the form most people use when filing their taxes, pdf here), you can pay by check, provided that the check is in the amount of $100 million or less. Per the form, “No checks of $100 million or more accepted. The IRS can’t accept a single check (including a cashier’s check) for amounts of $100,000,000 ($100 million) or more.” Their suggestion for getting around this limitation? “If you are sending $100 million or more by check, you will need to spread the payment over 2 or more checks with each check made out for an amount less than $100 million,” or you can “consider a method of payment other than check if the amount of the payment is over $100 million.” (If anyone wants to test the multi-check solution, help me find 100 million errors in Knuth’s books. That will net me $256 million. The taxes on that should exceed the threshold — I’m glad to pay the taxes on that over two checks and will report back my findings.)

From the Archives: Who is MP and Why Are His Initials on My Checks?: If you look closely at the signature line on Knuth’s check above, you’ll see the letters MP (trust me, it says MP) on the right. Here’s why.