The Banned Fashion Accessory You Wore on Your Head

Walk down the street in any American neighborhood today and you’re unlikely to see a lot of people wearing hats. Sure, you’ll find the occasional person in a baseball cap or something like that, but that’s hardly the norm. And in most downtown thoroughfares, you’ll rarely see anyone wearing any other type of hat.

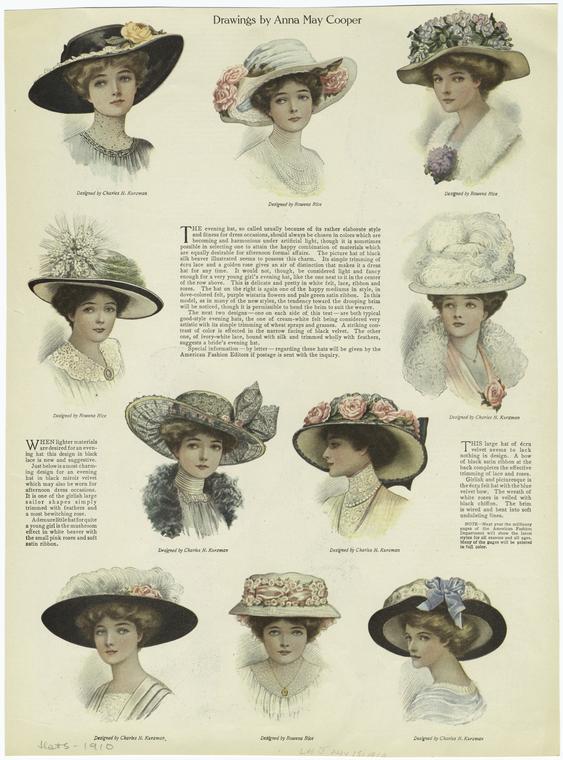

But that wasn’t always the case. For most of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, people wore hats everywhere. And in the early 1900s, American women — particularly those from wealthy families — wore rather large hats. Here’s an illustration of some of those hats from the 1910s (via the New York Public Library), below, and you’ll see for yourself.

Those are some big, ornate hats. In fact, they’re so big, it’s kind of amazing that they stayed on the women’s heads. A false step or a brisk wind could easily topple something that large.

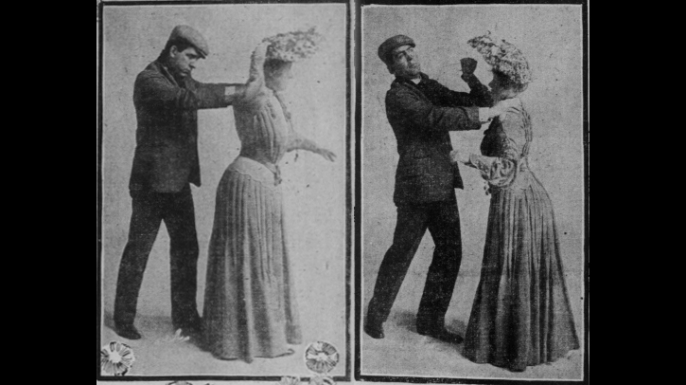

The solution? A hatpin. There are probably some in the pictures above, but you wouldn’t know — that’s part of their magic. These decorative pins had a flower, bow, metallic design, or another sort of ornate flair on one end and a long, pointy metal rod extending out from it, as seen in the illustration below. (The woman is holding the hatpin between her teeth.) Women would don the oversized hat and insert the pin such that the rod would run through their hair, parallel to their scalp, thereby holding the hat in place. The decorative end would be on display on the outside of the hat, perhaps being mistaken for part of the hat itself. For example, on the hat at the top-left of the image above, the yellow flower may have been the decorative end of a hatpin.

As the hats got larger, hatpins needed to get longer. As seen above, the pins could be very long, perhaps as long as a foot. They were fashionable and practical at the same time.

And they were also a very useful tool against men with vile motives.

At around the time super-large ladies’ hats became the norm, women also found themselves with a degree of independence that they hadn’t had before: they could walk down the street without a man escorting them. (Yes, this was only about a century ago.) And, by and large, these women were easy targets for thieves and abusers of all types — or so these men thought. Women with large hats also had long hatpins, and these hatpins could be used to fend off a would-be malfeasor. Mental Floss shares an early example:

In 1903, “Leoti Blaker, a young tourist from Kansas, was sitting on a crowded New York City stagecoach. A well-dressed fifty-something man got handsy with her, and when it became clear he wasn’t going to stop, Blaker moved to stop him herself. ‘At last I reached up and took a hatpin from my hat. I slid it around so I could give him a good dig, and ran that hatpin into him with all the force I possessed.’ she told The Evening World. The needle pierced the lecher’s arm, and he scurried away.

Baker’s story is hardly the only example. History Channels shares a similar story from 1912:

[One rainy day that year;] 18-year-old Elizabeth Foley found herself in the midst of an armed robbery. She had been walking home with a male colleague from the bank when someone came up behind them. In a flash, the robber swung his arms high and smashed her male companion in the head. The entire payroll for the staff was in his pocket.

Foley, however, was not shaken. In one swift movement she reached for her hatpin, jumped at the robber and aimed right for his face.

The hatpin defense was so common that one publisher even shared a how-to guide, as seen below.

But as women became more empowered, the powerful became more threatened. As Atlas Obscura explains, opponents of women-with-hatpins started to share stories of questionable validity, arguing that the hatpins were effectively murder weapons. And as a result, authorities began regulating hatpins. “By 1910, hatpins had become a national, and then international, threat. Lawmakers from Chicago to Kansas City and Hamburg to Paris began to write legislation that limited hatpins’ length or demanded that women put protective sheaths over the ends. In Chicago, women could be fined $50 for wearing hatpins more than nine inches long. Similar ordinances were passed everywhere from Milwaukee to Pittsburgh to New Orleans.” The laws were hard to enforce, though, as women around the world saw hatpins as a key to equality; in one instance in Australia, “sixty militant women [went] to jail rather than pay the moderate fines imposed upon them for wearing murderous weapons in their hats,” per a New York Times report.

The hatpin, though, was only valuable so long as the large hat trend continued. Hair and hat norms changed as the 1910s gave way to the 1920s, and the hatpin defense — and regulations — faded with the times.

Bonus fact: One of the reasons large hats fell out of favor? Animal welfare. In the late 1800s and into the time period discussed above, many women’s hats were decorated with birds. (As Pacific Standard shares, “one ornithologist reported taking two walks in Manhattan in 1886 and counting 700 hats, 525 of which were topped by feathers or birds.”) In 1918, the U.S. and Canada entered into a treaty that limited the ability of people to buy and sell migratory birds, dead or alive, and the bird hat craze came to a halt. Larger hats, which had in part been popular because they could handle the size of a bird, began to creep out of favor as well.

From the Archives: The Last Straw: When a big old fight broke out over the appropriateness of wearing straw hats.