The Checks That Saved 75 Christmases

In 2008, a man named Ted Gup received a gift from his 80-year-old mother: a large suitcase that once belonged to his grandfather, a man named Samuel Stone. The suitcase was labeled “memoirs,” so Gup likely expected to learn about the life and times of his long-passed grandpa. But what he found instead, at least on its face, had nothing to do with his grandfather at all. Dozens of pieces of a paper, all handwritten by different people, and all stories about the people who wrote them — not about Sam Stone. But as Gup started to read the notes, he learned the truth.

His grandfather was a hero.

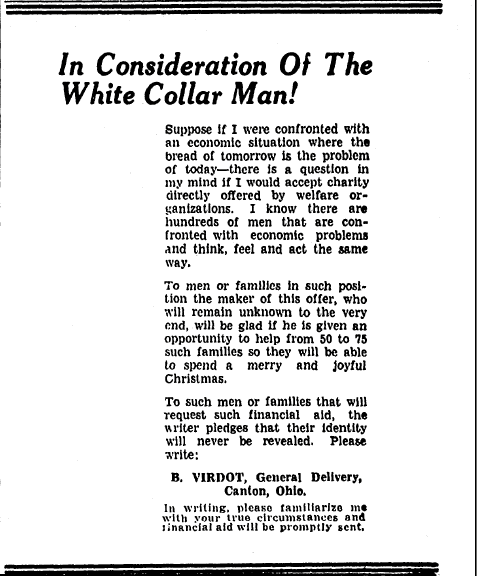

The story began 75 years prior. December 18, 1933, was a typical day for the people of in Stone’s hometown of Canton, Ohio — and for many, it wasn’t looking like it would be a very good day. Christmas was exactly a week away and that Christmas looked bleak. America was deep in the throes of the Great Depression; unemployment and poverty were at record highs. For many, the idea of hope was a cruel joke — years of struggle had sapped any sense of optimism for such things. So when the ad below appeared that day on page three of the Canton Repository, the local newspaper, many were skeptical. Someone — a man named B. Virdot — was offering them free money.

The ad, if you can’t quite make out the text, states that “the maker of this offer [ . . . ] will be glad if he is given an opportunity to help from 50 to 75 [families in need] so they will be able to spend a merry and joyful Christmas.” All the needy family needed to do was to write Mr. Virdot a letter “with your true circumstances” and “financial aid will be promptly sent.” Mr. Virdot even promised to keep the names of those requesting support a secret — “the writer pledges that their identity will never be revealed.”

The ad was so extraordinary that the newspaper itself decided to cover it in a front-page story. As Geneology Bank recounts, the Canton Repository ran an article titled “Man Who Felt Depression’s Sting to Help 75 Unfortunate Families,” giving immediate credibility to Virdot’s offer. Per the article, Virdot “set aside $750” — the equivalent of about $16,000 today — and “divided it into 75 $10 money orders.” Oh, and the article also mentioned a key point that the ad didn’t make clear: “B. Virdot” wasn’t the donor’s real name. He, like the people he wanted to help, intended to remain anonymous.

That didn’t stop people from writing, though. Many did, and many were pleasantly surprised to find return mail a few days latter — with the promised $10 of support included.

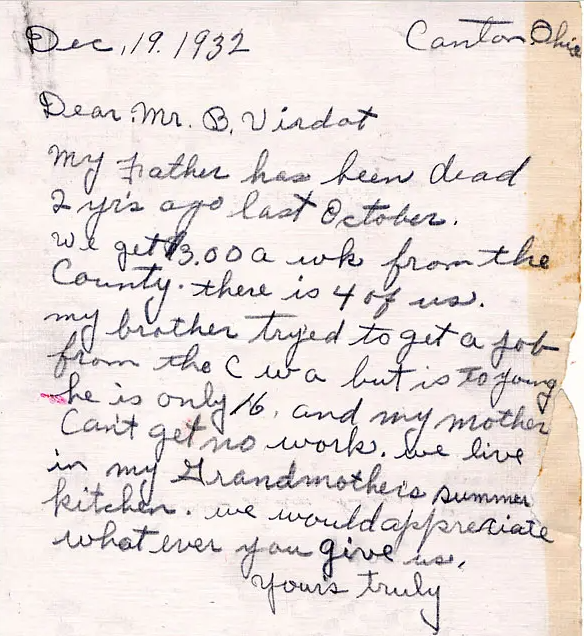

But until Ted Gup opened that suitcase, the story of B. Virdot was a mystery — and the stories of those in need were never told. Inside that suitcase, though, were those stories. There were dozens of letters, each addressed to a Mr. B. Virdot, sharing how the horrors of the Depression had impacted families in the Canton area, like the one below (via the New York Times).

Other letters shared even more painful experiences. Per a 2010 article in the Canton Repository, “the stories are wrenching: the mother with three children she couldn’t afford to feed adequately, the car dealer gone bankrupt, the wife too poor to buy a stamp for her letter,” and more tales of desperation. B. Virdot — now known to be Gup’s grandfather, Samuel Stone, responded. Under his pseudonym, Stone wrote checks to at least 75 of the families and perhaps as many as 150 — there were also stubs from checkbooks in the suitcase — and there’s every reason to believe that each one of those checks was cashed.

Gup, a former investigative journalist, spent the better part of a year trying to learn more about his grandfather’s history. Per the New York Times, Gup “discovered that [Stone] escaped poverty and persecution as a Jew in Romania to build a successful chain of clothing stores in the United States. He created the name B. Virdot by combining the names of his daughters, Barbara, Dorothy, and Mr. Gup’s mother, Virginia.” In an op-ed for the Times, Gup speculates that his grandfather could empathize with those in dire straits, and wanted to give back: “in 1902, when he was 15, he and his family had fled Romania, where they had been persecuted and stripped of the right to work because they were Jews,” and when they arrived in the United States, things were better — but not easy. He “worked on a barge and in a coal mine, swabbed out dirty soda bottles until the acid ate at his fingers and was even duped into being a strikebreaker, an episode that left him bloodied by nightsticks. He had been robbed at night and swindled in daylight. Midlife, he had been driven to the brink of bankruptcy, almost losing his clothing store and his home.”

For Stone, this was a way of giving back — and, accidentally, a way to make his grandson proud. In 2010, he published a book titled “A Secret Gift” about the B. Virdot letters and the joy his grandfather brought to hundreds.

Bonus fact: In 1896, the Presidency of the United States ran through Canton, Ohio — or, at least, the campaign of the successful candidate ran through there. Unlike politicians today, who visit voters where they are, William McKinley did the opposite and won. Wikipedia’s editors summarize the strategy: ” Instead of having McKinley travel to see the voters, [Republican National Committee chair] Mark Hanna brought 500,000 voters by train to McKinley’s home. Once there, McKinley would greet the men from his porch. His well-organized staff prepared both the remarks of the visiting delegations and the candidate’s responses, focusing the comments on the assigned topic of the day. The remarks were issued to the newsmen and telegraphed nationwide to appear in the next day’s papers. [McKinley’s opponent, William Jennings] Bryan, with practically no staff, gave much the same talk over and over again. McKinley labeled Bryan’s proposed social and economic reforms as a serious threat to the national economy. With the depression following the Panic of 1893 coming to an end, support for McKinley’s more conservative economic policies increased, while Bryan’s more radical policies began to lose support among Midwestern farmers and factory workers”

From the Archives: Pennies from Everywhere: A reverse-B. Virdot story?