The Hobo Code

Sometime in the mid-to-late 1800s, poor men, typically those finding difficulty finding jobs, took to the rails. These migratory workers hopped onto trains, riding illegally (but for free) in freight cars, bouncing around the country looking for work. For reasons lost to history, these people became known as “hobos.” They developed a less than sterling reputation, disregarding the law and often running afoul of those who nonetheless offered them accommodation. Further, they often lived the life of loners — you stayed where you were until the work dried up, moving on and leaving any friends or fellow vagabonds behind.

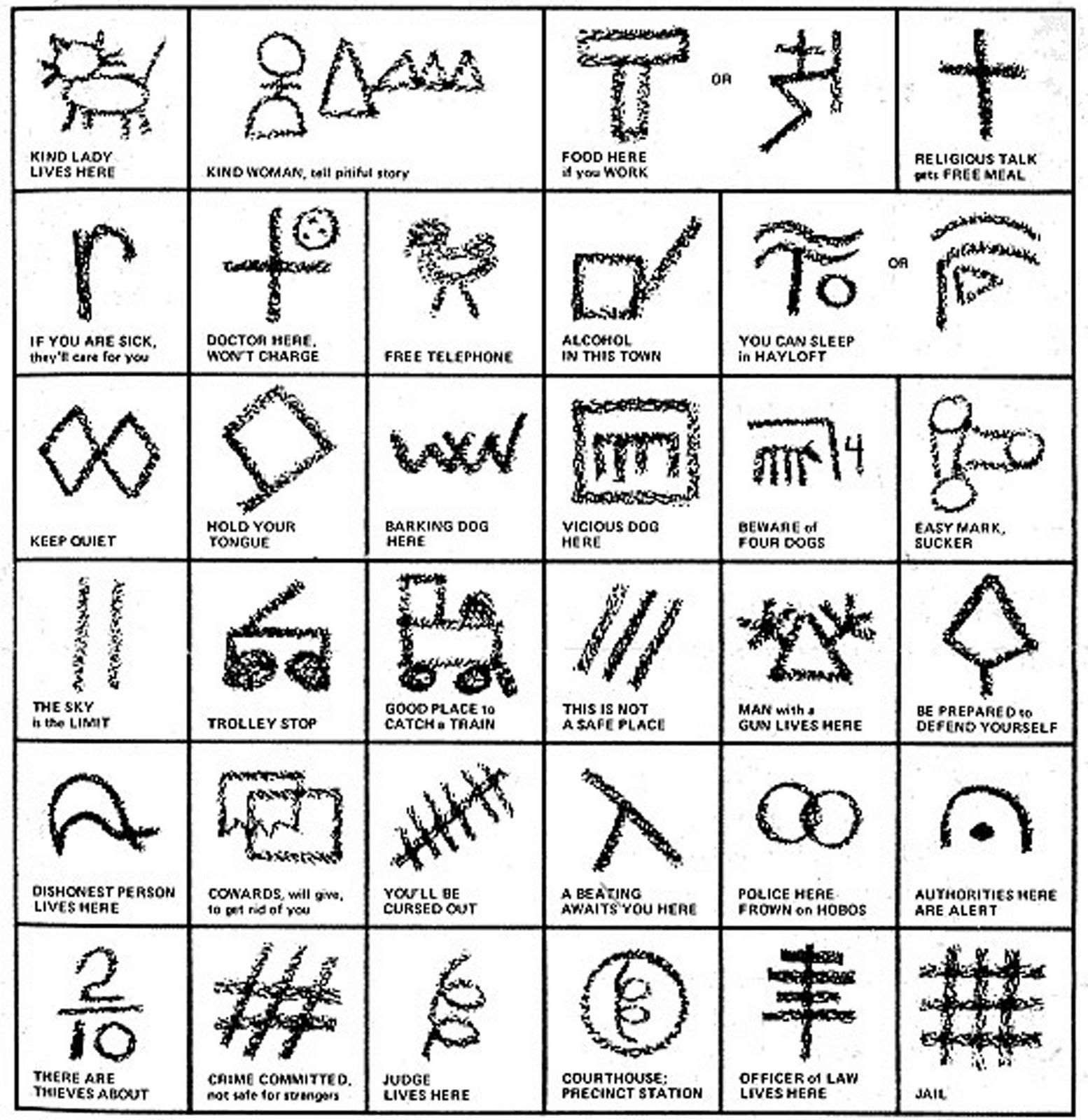

But this life of solitude didn’t mean that you didn’t look out for your fellow hobo. In fact, these transient workers found a way to help each other out — a series of glyphs known as the “hobo code.”

Some examples of the code can be seen above; a larger version of the image can be found here. The origins of the code, like the etymology of the term “hobo” itself, is unknown. But we do know that these images were adopted as an informal standard among the hobo community, loosely affiliated as it is. Many of the images make intuitive sense — the picture of a train suggests that the area is a good place to catch a train, for example. Others make sense with some explanation, such as the two interlocking rings which warn that police are in the area; the rings are intended to represent handcuffs. The origins of others are likely lost to modern eyes.

The code underscores the vaguely amoral lifestyle of hobos, one guided mostly by the pragmatic desire to survive than anything else. There are warnings about beatings and dishonest people, but there are also suggestions as where to get free medical care, free food, and some of the less-than-honest ways to obtain those. Some — “religious talk gets a free meal” and “kind woman, tell pitiful story” suggest that simply lying can yield positive results for the drifter. Others, such as “easy mark, sucker” suggests that worse behavior will prove even more fruitful. Wikipedia notes that “a square with a slanted roof (signifying a house) with an X through it” (not pictured) means that another hobo, perhaps the one leaving the mark, has already “burned” or “tricked” the house, suggesting that others stay away lest they take on the wrath intended for the scamming hobo. The code demonstrates that to be a successful hobo, you have to trust while being untrustworthy, and distrust while being honest.

Over time, we’ve lost the meaning to many of the symbols, even though they can still be seen in some places. For example, Wikipedia has a photo, here, of a ferry crossing in New Orleans which has what appear to be hobo code signs — ones which have not yet been translated.

Bonus Fact: One other way hobos create a sense of community? The National Hobo Convention. Each year, self-proclaimed hobos such as “Connecticut Shorty,” “Slo Freight Ben,” “Grandpa Dudley,” and “Bo Grump” gather in Britt, Iowa and elect themselves a King and Queen, although it is unclear at best to what the honorific entitles the victorious candidate.

From the Archives: Hug Me Dot: The secret code of Mensa conventions.

Related: A book of hobo code poems. It only has three reviews and two of them say the book stinks, but … it’s a book of hobo code poems, and the fact that it exists all but requires a mention, right?