The Horse Hide

Technology has dramatically changed what warfare looks like. Today, factions use laser-guided rockets, drones, satellites, and space-age mechanisms using self-sealing stem bolts or something or other. Turn back the clock a century, though, and war looked a lot different. In World War I, the technology of war was limited, with trenches, machine guns, sniper rifles, and artillery topping the list.

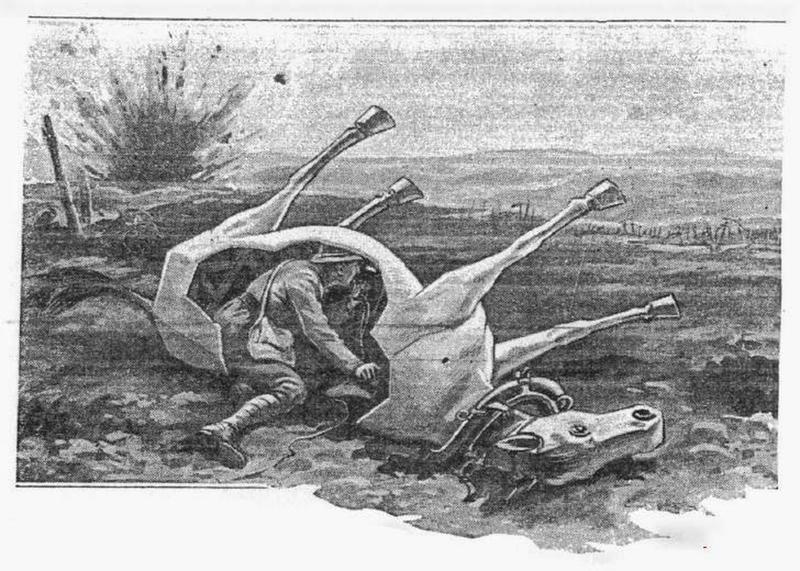

And, of course, the papier-mache horses.

Okay, maybe that was only a one-time thing.

Trench warfare, by modern standards, is kind of crazy. Each side would dig long holes — trenches — in order to protect their troops from gunfire and, to a lesser degree, artillery fire as well. If you exited the trench and made your way toward the enemy’s trench, you risked getting shot — you were out in the open, with little to protect you. The area between opposing trenches, known colloquially as “no man’s land,” was incredibly dangerous — but also strategically important. If you could create an outpost in no man’s land, you could monitor your adversary’s movements, using that information to help guide your attacks.

Which is, in part, how the picture above happened. Horses — real ones, not the papier-mache variety — were valuable assets in World War I. As We Are The Mighty notes, horses “pulled ambulances, carried soldiers into cavalry charges, and were the primary means of transporting weapons, ammunition, and food supplies for each nation involved.” But when a horse got loose and traveled into no man’s land, it often didn’t come back. Big, loud, and not aware of the dangers ahead, a rogue horse made for an easy target.

And that’s exactly what happened at some point during the war. As Popular Mechanics reported back in 1918 (here’s a pdf), a French horse galloped into the danger zone and, as one would expect, was quickly felled by enemy fire. A dead horse is no good to either side, so the horse’s carcass just sat there, undisturbed — until someone in the French military had an interesting idea. As seen here, the French had already been experimenting with papier-mache as a way to create decoys; they made real-ish looking heads and put them on sticks, and then popped the heads out from the trenches to draw fire. Seeing an opportunity, they decided to up their papier-mache game. As Popular Mechanics explains, “the French [ . . . ] set camouflage artists at work fashioning a papier-mache replica of the dead animal. Under cover of darkness, the carcass was replaced with the dummy.” A French soldier crawled into the horse-shaped shell, and, as History Daily explains, brought with him “a telephone wire that ran back to his own trenches so he could send back reports of German movements.”

Unfortunately for the French, the fake horse didn’t actually provide much protection from artillery fire. After three days, according to Popular Mechanics, the Germans caught wind of the ploy, noticing a person crawling out of the horse hideyhole during a shift change. The Germans blew up the fake horse in short order, but per War History Online, “the first attempt was considered such a success it went on to be used again on a number of occasions.”

Whether those proved ultimately successful is, sadly, unknown, and even worse, no papier-mache “horse” hideouts exist from the war are still in existence today.

Bonus fact: An odd casualty of the First World War? Mustaches. During the Crimean War, many British troops began growing mustaches and beards, likely to help them face (sorry!) the cold weather. The British people approved of mustaches, in particular, seeing them as a sign of manliness, and before the war was out, the military required that troops not shave above the lip. But gas emerged as a weapon of choice during World War I, and British soldiers were issued gas masks in response. As War History Online explains, “facial hair could prevent a perfect seal from being made between the skin and the mask,” so in October 1916, the British military dropped the mustache requirement.

From the Archives: The Christmas Truce: A brief moment in World War I when the two sides stopped fighting and instead, celebrated the holiday — together.