The Internet’s Hidden Teapot

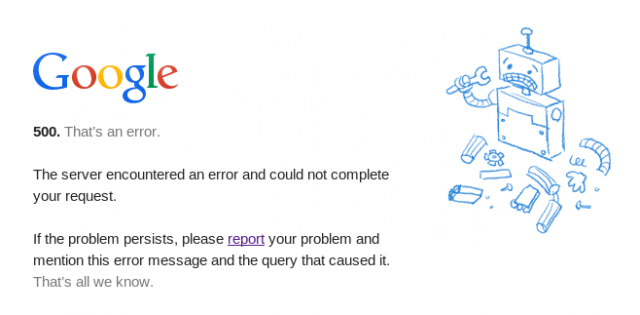

Every once in a while, something on the Internet breaks. You’ve probably experienced it before. For example, what happens when you go to a website but the server is offline for one reason or another? You’ll see something like this:

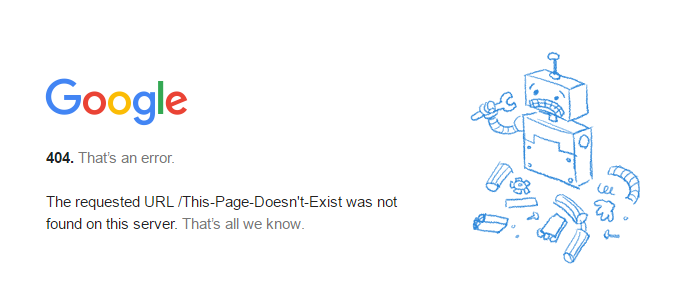

Or maybe the server is working fine and dandy — it just doesn’t have the content you’re looking for. It’s gone, for some reason. Then, maybe you’ll see something like this:

In one sense, they’re very similar errors — you wanted to read or watch or listen to something, but, nope, you’re not going to be able to because something is broken. It’s not you, it’s them. The Internet has all sorts of reasons for not giving you the content you demand. Really, there’s a whole list, and each has its own status code. Status code 500 — that’s the top image — means “internal server error.” It’s the catch-all error message for when the server can’t do what you asked but doesn’t know why. The bottom one, 404 (“not found”), is what you get when you go to a URL which doesn’t exist. A couple of other common ones are 503 (“service unavailable” — the website is down, typically temporarily due to something like having too much traffic) and 403 (“forbidden” — you don’t have permission to view that page). Wikipedia has a complete list, here.

Many websites have custom error pages, and Google, as seen above, is no exception. But there’s one error page that Google has that many do not. You can check it out here — at http://google.com/teapot — but seeing the URL and image below will save you a click.

Why does Google have a teapot page? If you didn’t click that link Wikipedia like above and study it, you might be confused. The Google page is an homage to status code 418, which is also known as “I’m a teapot.”

Google, it should go without saying, isn’t a teapot. Neither is any other website, at least not in a functional, tea-making sense. So, why does Google have hidden a teapot page? It is an homage to, perhaps, the first Internet April Fool’s joke.

The protocol that our web browsers use is called Hypertext Transfer Protocol, or HTTP. You almost certainly know those four letters — they’re the quartet that preceeds the colon-slash-slash in website addresses. In the early days of networked computing — as in, before the Internet was the Internet — developers had to come up with a way for computers to connect with one another. One computer scientist, Tim Berners-Lee, issued a request for comment (“RFC”) describing his proposed standard for how that could happen. Berners-Lee’s proposal was HTTP, and eventually, that became the protocol we know and love today.

But the RFC process was ripe for lampooning. On April 1, 1998, a man named Larry Masinter — the principal scientist for Xeroc PARC, one of the leading tech think tanks at the time — did exactly that. He issued a request for comment titled “The Hyper Text Coffee Pot Control Protocol for Tea Efflux Appliances,” or HTCPCP-TEA. (Say the initialism aloud and it sounds, kind of, like HTTP.) The RFC, available here, is excessively hamfisted and tongue-in-cheek, as you’d expect from an April Fool’s joke, and unless you’re really in on the joke, it isn’t all that funny. But it still purports to do something real; as one tech blog summarizes, the RFC intended to create a “brand new protocol for controlling, monitoring, and diagnosing coffee pots.” Or, for those of us lay people, it’s basically a way to use your web browser to make coffee. That would be great, but alas, it’s fake.

And yet, it spread throughout the tiny Internet community of the time. And one section of the RFC stood out — the teapot problem. What, the RFC wondered, should happen if someone tries to make coffee in a teapot? Teapots can’t make coffee, after all; they make tea. The RFC has a solution: “any attempt to brew coffee with a teapot should result in the error code ‘418 I’m a teapot,'” decided Masinter. He continued that “the resulting entity body MAY be short and stout.”

Again, the joke was — well, it takes a certain person to appreciate that type of humor. But to Masinter’s credit, he knew his audience. The “Status Code 418: I’m a Teapot” joke spread throughout the compsci circles as sort of an in-joke. Even years later, some webmasters began creating pages about the joke and, eventually, Google got in on the fun. No teapots were connected to the non-existent coffee-making version of the Internet, though. But who knows what the future will hold.

(As an added bonus: if you visit Google’s teapot page on a smartphone wth an accelerometer, you can tip your phone to make the teapot pour some tea out.)

Bonus fact: In 1939, a dance instructor named George Harold Sanders developed a song with a dance routine to help kids learn how to tap dance. His idea was to give young children something familiar to pantomime: a tea kettle, ready to pour a cup of hot water. From that, the song “I’m a Little Teapot” was born. Oh, and those dance moves? They have a name: “the Teapot Tip.”

From the Archives: The Swedish Coffee (and Tea) Experiment: Probably the world’s worst PR campaign, at least in the beverage category.

Related: A wifi-enabled tea kettle. The joke has started to come full-circle.