The Nazis of New York

Pictured above are a bunch of German men marching in front of a Nazi banner. If you look carefully at the white sign in the center of the backdrop, you may notice the date — it reads 1937, a year before the Munich Agreement and Germany’s annexation of part of Czechoslovakia. These Germans seen above were loyal to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime, much like many other Germans at the time.

But these Nazis were different — they weren’t in Germany. They were in the suburbs of New York City.

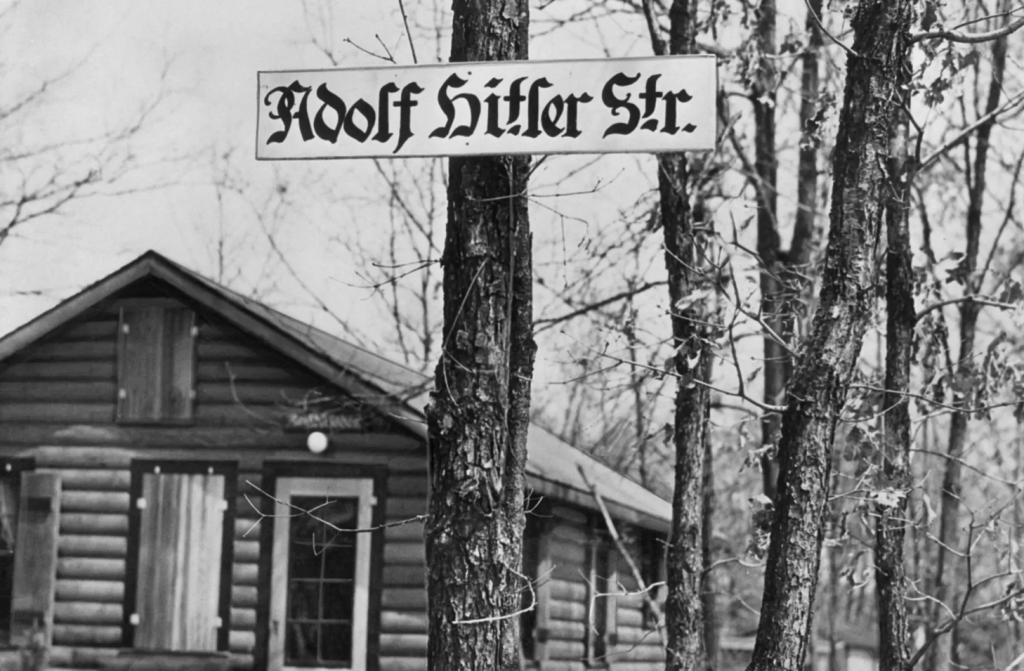

The image above comes from a place called Camp Siegfried, a summer camp that operated in Yaphank, NY, about a 90-minute drive from Manhattan. (Here’s a map.) Like most summer camps of the time, Camp Siegfried had a swimming pool, hiking trails, an archery range, and lots of other outdoor activities. But there was more than just campfires and cookouts — Camp Siegfried was a little spot of Nazi Germany situated on Long Island. The grounds featured Nazi and Hitler Youth flags and pictures of Hitler himself throughout the complex. There was even an Adolf Hitler Street, as seen below (via the New York Times).

According to the Museum of Jewish Heritage, the camp was owned by the German-American Bund, a “pro-Nazi group [that] was formed in the United States to advocate for policies beneficial to Germany [and] was very active throughout the latter half of the 1930s, organizing rallies and marches, including a rally at Madison Square Garden in 1939.” As a result, Camp Siegfried was not unique — there were similar camps in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin — nor was it a big secret. Rather, it was very popular. According to the Forward, “At its height, [. . . ] tens of thousands of people arrived via Long Island Rail Road, from Penn Station, taking a train called the ‘Camp Siegfried Special.’”

The camp shut down in 1941, around when the United States entered World War II to fight against Nazism. But its legacy persisted for generations. Part of the camp transitioned into a private community called “German Gardens” and was bound by a restricted covenant — as the New York Times reported, “the original owners of this tract of land kept a clause in its bylaws requiring the homeowners to be primarily ‘of German extraction.'” If you wanted to buy a home there, you needed to get permission from a community organization called the German American Settlement League, and the GASL wouldn’t let you buy unless you had German ancestry. And this restriction didn’t go away when the Nazis went away, either — not even close. It would persist for more than 75 years.

Today, anyone can (finally) live in this little part of New York if they so choose. In 2016, a federal court judge ruled that the community’s by-laws were not in compliance with fair housing laws, so the community re-wrote those by-laws — and, effectively, ignored them. A year later, New York’s attorney general sued the GASL, claiming it was still engaged in discrimination; the two parties settled and GASL agreed to end its discriminatory practices.

Bonus fact: The leader of the German-American Bund was a German-born, naturalized American citizen named Fritz Julius Kuhn — and he’s one of the few Americans to have his citizenship revoked. In 1939, New York audited Kuhn and discovered that he had embezzled nearly $15,000 from the Bund (approximately $250,000 in today’s dollars) and charged him with larceny and forgery. New York did so, though, without the Bund’s cooperation. They believed that leaders should have absolute power and should be treated as above the law (echoing the Nazi principle of Führerprinzip) and did not want Kuhn prosecuted. The state proceeded nevertheless and secured a conviction, and after his release, he was re-arrested, this time by the federal government. Kuhn was charged with bein an agent of an enemy state, convicted, had his citizen revoked, and was deported to Germany.

From the Archives: When The Nazis Invaded America: An actual invasion — that didn’t go as planned, thankfully.