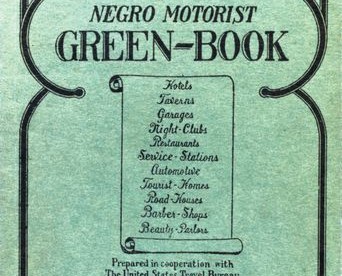

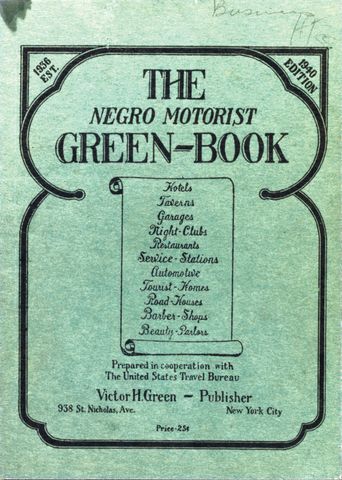

The Negro Motorist Green Book

Every year, Zagat publishes a series of guides to the restaurants in virtually every major city in the United States. The guides feature short, curated descriptions of each eatery, touching upon the must-have (or must-avoid) dishes, the service, the decor, and of course, the price. But what Zagat doesn’t tell you is if they’ll serve you if you’re black.

Hopefully, there’s good reason for that — for more than fifty years, it’s been illegal for a restaurant in the United States to refuse service to a diner on the basis of his or her race, and culturally, doing so is simply unacceptable. But again, that wasn’t true a half-century or so ago. For an African-American family, traveling through certain parts of the country was difficult, as finding a place to eat or sleep which wanted your business could be hard to come by.

And before the law could catch up to the problem, a postal worker did.

The result: the Negro Motorist Green Book, as seen below.

In 1932, that postal worker, an African-American named Victor H. Green, came up with the idea for a guidebook which would detail the places which welcomed black travelers. Green’s first edition, which came out four years later in 1936, focused on restaurants and hotels New York City area, as that’s where he lived and had first-hand knowledge.

The guide proved popular, so Green looked to expand its reach. He asked his readers to send in tips; any accepted tip would earn the correspondent a dollar, per Wikipedia, and by 1941, Green upped the bounty to $5. He also asked his fellow postal workers to help research; according to the New York Times, many mail carriers would “ask around on their routes” in furtherance of Greens’ efforts. The plan succeeded: as CNN notes, with these tips, the guide “eventually expanded to include everything from lodging and gas stations to tailor shops and doctor’s offices across the nation, as well as in Bermuda, Mexico, and Canada.”

Beyond being a boon for those being discriminated against, the Green Book was a commercial success as well. Many black-friendly businesses advertised in it. Esso, a precursor brand to ExxonMobile, was a particularly important one — not only was the chain of gas stations a financial supporter of the Green Book, but it was also a major distributor of it. (Esso, as another New York Times article notes, was one of the few companies at the time in that it allowed African-Americans to become franchisees.) Before the 1940s were out, the Negro Motorist Green Book became a must-have guide for tens of thousands of African-American travelers, to the benefit of the larger community as well.

But for good reason, the Green Book no longer exists. With the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it became effectively obsolete. Victor Green published its final edition in 1966, and physical copies are hard to come by today. However, if you’d like to browse through a virtual version, the Spring 1956 edition is available here.

Bonus fact: Martin Luther King, Jr., and his wife, Coretta Scott, were married on June 18, 1953 — but their honeymoon wasn’t spent at a hotel, as the ones nearby did not accept African-American guests. According to the book “The Wisdom of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” the two spent their first evening together at a funeral home.

From the Archives: Rosa Parks’ First Ride: Rosa Parks’ famous, segregation-busting bus ride was in 1955 — but it wasn’t her first time conflicting with a bus driver over discrimination.

Take the Quiz: Can you name the 107 most frequently used words in Rev Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech?

Related: “Remembering Jim Crow: African Americans Tell About Life in the Segregated South” by William Henry Chafe and Raymond Gavins. Fifteen reviews, all but one is a five-star review.