The Niihau Incident

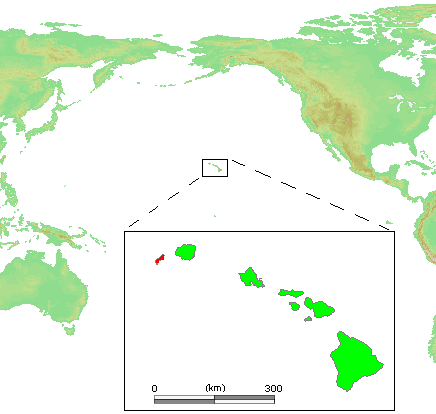

December 7, 1941 is, of course, Pearl Harbor Day, when the Japanese Imperial Navy struck the American naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, killing nearly 2,500 U.S. servicemen. While folklore often refers to the Japanese assault as focused on one-way kamikaze missions with pilots not expecting to return, this isn’t the case. The Japanese navy realized that many planes would be too damaged to return safely to their aircraft carriers. Niihau, pictured red in the inset above, was designated as a rendezvous point. Niihau made a lot of sense: it was only a 30 minute flight from Pearl Harbor; is tiny (70 square miles or 180 km^2), making it easy to find those awaiting rescue; and was uninhabited, reducing the risk of assault or capture dramatically. Pilots were told to fly to Niihau and wait there until a submarine could surface and pick them up.

A solid plan, for sure, but one that went horribly wrong. Niihau wasn’t very easy to get to from Pearl Harbor after all, and only one Japanese pilot safely made it to its shores. And more importantly, Niihau wasn’t uninhabited.

At the time, Niihau was owned — yes, someone owned the whole island — by a man named Aylmer Robinson. (His ancestors purchased it from King Kamehameha V and the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1864.) Robinson didn’t live there, though; he governed it from Kaua’i, the larger island to Niihau’s east. Robinson rarely allowed outsiders to visit. As an unintended consequence, few people other than the handful of native Hawaiians on Niihau ever had the opportunity to learn more about it.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, a Japanese airman named Shigenori Nishikaichi crash landed on Niihau, as planned. Nishikaichi’s plane came down just a few yards away from one of Niihau’s inhabitants, named Hawila Kaleohano. Kaleohano, like the other residents of the island, was unaware of the day’s events, but knew that Japan and the United States had been saber-rattling for months. Kaleohano, acting on this information, took the pilot’s weapon and the documents he was carrying before Nishikaichi came to. But the two would be hard-pressed to interact further. Nishikaichi spoke only Japanese. Kaleohano and, for that matter, most of the islanders did not. They only spoke Hawaiian.

There were a few exceptions, though. Most notably were Yoshio and Irene Harada, a husband and wife of Japanese descent, both of whom spoke Japanese. Nishikaichi told the Haradas of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the Haradas decided to not share that information with the non-Japanese islanders. But over the next few days, after the island residents threw a party for Nishikaichi, many sat around listening to the radio, and learned about the true reason Nishikaichi was on Niihau. Robinson was due to visit Niihau the next day (as he or his representative did every week), and they decided that Nishikaichi would be given over to Robinson’s custody, to return to Kaua’i with their landlord. But Robinson never showed up. Unbeknownst to those on Niihau, the U.S. military had stopped all naval traffic in the area, and Robinson was stuck on Kaua’i. When he failed to arrive, the Haradas offered to keep Nishikaichi in their hut, which the rest of the population agreed to — provided that five others be stationed outside their hut, in shifts, as makeshift security guards.

They probably shouldn’t have taken shifts. The Haradas and Nishikaichi overpowered a guard and obtained two guns from a nearby warehouse. On the evening of December 12th, as villagers fled into the thickets and to beaches across the island, the trio began a hunt for Nishikaichi’s documents — and, therefore, for Kaleohano. But neither were to be found. Kaleohano had handed the documents off to one of his relatives and then left the island, on a ten-hour boat ride to find Robinson. Nishikaichi burned his house to the ground and, with Mr. Harada’s help, took captive a woman named Ella Kanahele. Using her as leverage, Nishikaichi ordered her husband, Ben, to track down Kaleohano and bring him to them. Ben Kanahele knew that Kaleohano had left the island, but delayed as long as he could. When he returned empty handed, Harada told him that Nishikaichi was planning to kill everyone until and unless Kaleohano returned.

So Ben Kanahele attacked first, wrestling Nishikaichi to the ground. Nishikaichi fired his pistol at Ben, striking him three times, but Ella jumped in to save her husband. Harada then pulled Ella off of Nishikaichi, but by then, Ben was able to pick the pilot up and slam him into a wall and ultimately, slit his throat with a knife after Ella struck Nishikaichi in the head with a rock. Harada turned a shotgun on himself and committed suicide. Robinson arrived the next day, and Irene Harada was taken into custody, as was the only other person of Japanese descent on the island.

The Niihau incident, as this is now called, made headlines throughout the country. Ben Kanahele was cited for his bravery and, despite being a private citizen, was awarded a Purple Heart. Irene Harada was imprisoned for two and a half years, although never convicted of a crime, and the actions she and her husband took are often cited as an early driver of fears that Japanese-Americans would be loyal to Japan during the war. One place that this fear was not realized, however, was Hawaii — as Wikipedia notes, “during the [Niihau] incident, the Territorial Governor of Hawaii rejected calls for mass internment of the Japanese-Americans living there.

Bonus fact: The Robinson family still owns Niihau. According to Wikipedia, the two brothers who now head the family have been offered $1 billion to sell the island to the U.S. Federal government, but have declined repeatedly.

From the Archives: Hawaii Dollars: Special money for Hawaii, from World War II.

Related: “The Niihau Incident: The True Story of the Japanese Fighter Pilot Who, After the Pearl Harbor Attack, Crash-Landed on the Hawaiian Island of Niihau and Terrorized the Residents” by Allan Beekman. 3.9 stars on 11 reviews and a really, really, really long title. Really.