The Not-Quite-Vice-President Who Was Almost Accidentally President

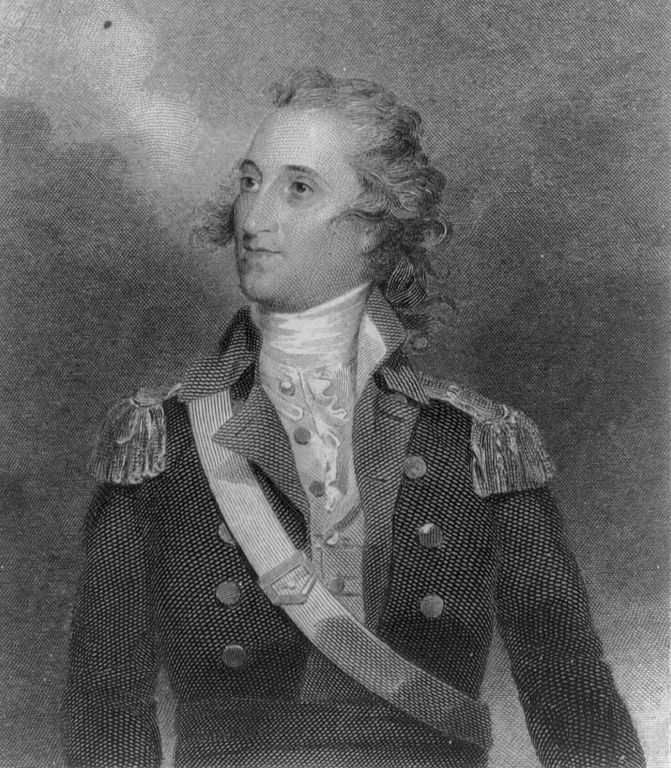

The guy pictured above is Thomas Pinckney, and it’s unlikely you’ve ever heard of him. He was the Governor of South Carolina from February of 1787 until January of 1789, was the second U.S. ambassador (then titled “minister”) to the United Kingdom, and then served as one of South Carolina’s representatives in Congress for about three-and-a-half years. A great resume, but hardly one that makes him into a household name.

And yet, he probably should have been the second Vice President of the United States. And he probably would have been, except for the fact that he almost accidentally became President instead.

The presidential election of 1796 featured two superstar candidates going head-to-head. John Adams, of the Federalist Party, was the incumbent Vice President, having served under George Washington for the two years prior. His opponent was Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, who had served as Washington’s first Secretary of State. In modern parlance, Adams’s running mate was the aforementioned Thomas Pinckney; Jefferson’s was Aaron Burr. Adams won the election, earning 71 electoral votes to Jefferson’s 68. (If you’re unfamiliar with how the U.S. electoral vote system works, I summarized it previously in the second paragraph, here.)

In modern times, Adams would have become President and Pinckney his Vice President. But under the Constitution at the time, that’s not how it worked out. Today, electors vote for President and Vice President separately; that is, they each cast one vote for a Presidential candidate and one vote for a Vice Presidential candidate. But before 1804, the process worked differently — and not well. Each elector cast two votes, without differentiating between “President” and “Vice President.” The candidate with the most votes became President; the candidate with the next-most votes became Vice President.

That system had an obvious flaw, though, as demonstrated by the 1796 contest. The 71 voters who supported the Federalists each cast a vote for Adams. But, in theory, each should have also cast their second vote for his running mate, Pinckney. That would result in a tie, which wasn’t the intended outcome. (This result happened four years later; Jefferson and Burr ran again but, this time, won. Both Jefferson and Burr received the same number of votes, though, creating a ton of turmoil, and resulting in an amendment to the Constitution before the 1804 election.) To avoid that tie, at least one Federalist voter had to vote for someone other than Pinckney.

In an era before phones and emails etc., that would have probably been easy. But coordination without real-time communication proved impossible. And to complicate things, Adams’ main in-party rival, Alexander Hamilton, was rumored to be scheming. Despite the fact that both Adams and Hamilton were both Federalists, they weren’t friends. Hamilton, rumor had it, was working on a plan to get Pinckney — not Adams — elected President.

Both Hamilton and the Democratic-Republicans knew that Jefferson was going to lose the election, but neither wanted Adams to ascend to the Presidency. So Hamilton, allegedly, tried to get some of Jefferson’s electors to vote for Pinckney with their second vote (in lieu of Burr). Jefferson had earned roughly 68 votes; if Hamilton could get enough of those 68 Jefferson voters to cast that second vote for Pinckney, those votes — combined with the ones Pinckney would get by virtue of his alliance with Adams — would vault Pinckney into first place, and therefore into the Presidency.

The Adams-loyal Federalists didn’t want this to happen, of course. But there was only one way to ensure Pinckney from getting more votes than Adams — the Federalists electors had to split their second votes among a few different candidates, at Pinckney’s expense. And that’s exactly what they did. Of the 71 electors who voted for John Adams, only 50 cast their second ballot for Pinckney. And, for Adams’ sake, it’s a good thing that they did. Nine of Jefferson’s voters — eight from Pinckney’s home state of South Carolina and one from Pennsylvania — also ended up voting for Pinckney. Had almost all of Adams’ electors also voted for Pinckney, Pinckney would have likely ended up with more votes as Adams, and therefore, as President of the United States.

But Pinckney didn’t just miss out on becoming President — he also missed out on becoming the Vice President. John Adams won the election with 71 electoral votes; Jefferson came in second with 68, becoming VP. Pinckney’s 59 votes relegate him to a footnote in history, even though his running mate won — and despite the fact that had things gone slightly differently, he could have very easily been President.

Bonus fact: Jefferson had a habit of beating Pinckneys. In 1800, the Federalists again nominated an Adams-Pinckney ticket, but it wasn’t Thomas Pinckney backing up John Adams; the Federalist’s VP nominee was his brother, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. Jefferson won the election, and in 1804, ran for re-election. His opponent? Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. And Jefferson won, again. The Federalists gave Charles Cotesworth Pinckney a third chance in 1808, but he lost, again, this time to James Madison.

From the Archives: Jefferson’s Code: What Thomas Jefferson left behind.