The Other Way Salmon Furthers Brain Development

Omega-3s are a type of fatty acid which, studies suggest, are good for brain development. And salmon are a good source of omega-3 fatty acids, so indirectly, they’re good for our brains. And they’re good for something else neurological, too — they can help us learn how our brains work.

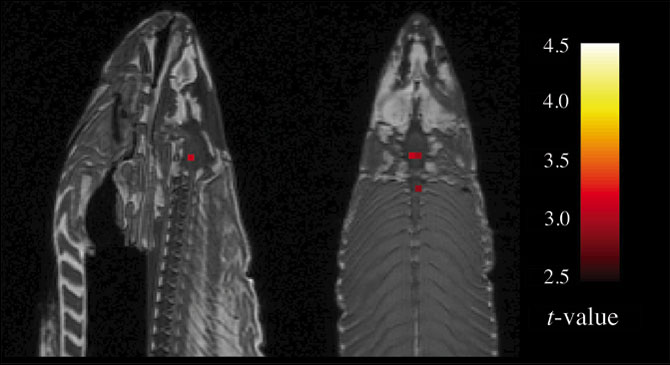

But only because of an incredibly silly idea — the decision to take an fMRI of a dead salmon, seen below.

An fMRI is a “functional magnetic resonance image” — it’s used to “measures changes in blood oxygenation levels in the brain during tasks,” according to Scientific American. Basically, doctors and other researchers use the tool to see how our brains — human brains, that is — react to certain stimuli. In the example we’re about to discuss, the test subject was shown a series of pictures from various social situations. (The theory: some of us are extroverts and thrive in these situations, others are more introverted and shirk away from the environment, and our brain oxygenation may be able to show those differences.) But in order to use an fMRI, you are supposed to test the machine beforehand and get a baseline image, so you know which spots are due to our brain activity, and which ones are due to various other factors. Makes sense. But it doesn’t always happen — many researchers simply skipped this step, seeing it as a waste of time.

Typically, scientists who do test first will use a balloon filled with mineral oil to check for problem spots. Balloons filled with mineral oil don’t have any brains, and therefore don’t have any brain activity, so anything that shows up is by definition a false positive. But in 2009, a team of researchers led by Craig Bennett, a psychology professor at the University of California Santa Barbara, decided to use a different set of test objects, hoping to get a better view of the fMRI machine’s default data. First, they tried a pumpkin, but that wasn’t all that useful, as pumpkins are filled with seeds and pumpkin guts, and not much else. So they decided to get something more complex. Bennett went to the fish market and bought a fresh, but dead, full salmon.

Bennett and team decided to run the “show photos of social situations and measure brain activity” experiment on the dead fish. They’d hold up the photo, take the scan, and look at the results. (Researchers often have a strange sense of humor, but if you’re one of the nearly 1.8 million people who have seen this video, you knew that already.) And what they saw was brain activity, as evidenced by the red areas (called “voxels,” or 3-D “pixels,” as Wired explained) above. That, as the team noted it their brief paper, were clearly false positives. After all, a living fish wouldn’t be able to comprehend the images being shown it; a dead fish, well, dead fish don’t think at all.

So how does this help science move forward? In an interview with BoingBoing, Bennett analogized the fMRI to a game of darts — “it’s like having 60,000 darts you can throw. Some will hit the bullseye by chance and we need to try to correct for that.” And at the time, Bennett stated, “40% of papers published in 2008 didn’t do proper correction.” Bennett and team put together a poster showing their results (available here, pdf) which aimed to show that false positives are real, common, and can be accounted for — it was, in a sense, a PR campaign for best fMRI practices.

And apparently, it worked. By the time the above-linked Scientific American article about the study was published — in 2012 — the number of new papers without the proper correction applied made dropped — only 10% of those published had the problem.

Bonus Fact: If you’ve ever eaten salmon, you know that it is typically pink. (Crayon giant Crayola agrees; this is what their “salmon” color looks like; and in case you were wondering, it’s named for the fish, not the other way around.) That’s because salmon eat krill and shrimp. But farm-raised salmon don’t feast on a diet high in crustaceans, so their flesh should be almost white. It isn’t though, because farm-raised salmon is often fed food with artificial coloring — all in an effort to make the fish we eat seem more natural.

From the Archives: Fred’s Fish: It’s a story about Mister Rogers; you are therefore ethically obligated to read it and share it with everyone you know.

Related: “The Salmon of Doubt” by Douglas Adams. If you aren’t familiar with it, you should buy this book instead and read it immediately.