The Road Repair That Broke Science

Pictured above is a Google Street View glimpse into the intersection of Rose and Prospect Streets in Hayward, California, a suburb of San Francisco. What you’ll notice, probably, is nothing — except for some pretty wild grass growing next to the sidewalk, there’s really nothing notable about the screen capture above. And that’s too bad, because there used to be.

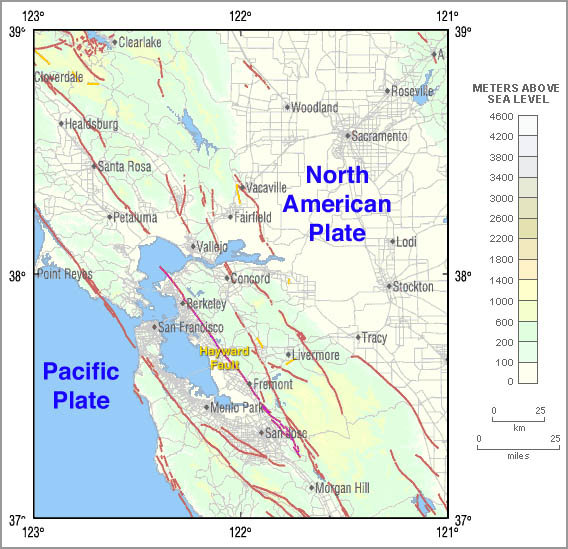

San Francisco is known for a lot of things, but one of the bad ones is earthquakes. The Bay Area straddles the line between the Pacific Plate and North American Plate, and those plates are shifting slowly over time. As seen in the map below (via Wikipedia), there are a lot of geological fault lines in the area where those two plates don’t line up perfectly. And if you look closely toward the middle of that map, you’ll see one of the fault lines is labeled the Hayward Fault.

The Hayward Fault, as the common names would suggest, runs through Hayward, California. Earthquakes aside, though, residents of the town probably never noticed the ground moving slowly beneath their feet. But in the 1970s, someone noticed that something was off — the curb, seen in red above, was misaligned. Here’s a picture of that same curb from 1971 (via here, which has a handful of pictures of the curb).

This wasn’t a function of bad construction, though. It was the fault of the Hayward fault. Around that time, some geologists realized that when the city built the curb, they managed to place it nearly perfectly perpendicular to the fault line; as the plates below shifted, the curb separated.

And they kept separating for decades. This gave geologists a unique opportunity — by visiting the intersection of Rose and Prospect on regular intervals, they could measure the shift of plates over time, and with decent precision. That’s exactly what they did. As the Los Angeles Times reported, “since at least the 1970s, scientists have painstakingly photographed the curb as the Hayward fault pushed it farther and farther out of alignment. It was a sharp reminder that someday, a magnitude 7 earthquake would strike directly beneath one of the most heavily populated areas in Northern California.”

For the next forty-plus years, geologists kept detailed records and photos of the curb movement, finding that it moves “a little bit every year – maybe about 4 millimeters,” and “over the years, it’s moved it 8 inches” in total, per NPR. In or around the year 2005, the city went to fix the curb, but the scientific value prevailed; as the New York Times reported, researchers in the area wrote in asking them not to, and the city agreed. But in 2016, the city forgot. Per the Times, “the city government has experienced a lot of turnover in the [subsequent] decade, and that there was no documentation in the city’s computer system indicating that the curb should not have been altered.” In 2016, and as reflected in the Google Street View capture above, the city fixed the curb.

But don’t bemoan the loss of this little bit of scientific history too much. While it’s neat to be able to measure the shift of the plates, there’s a strong argument to be made that the Hayward curb was more a curiosity than a valuable tool — the big concern with plate shifting is earthquakes, not a 4mm annual creep. On the other hand, a broken curb is a tripping hazard for pedestrians and an obstacle for those who use wheelchairs. And in any event, if we wait long enough, the curbs will start to separate again.

Bonus fact: If you’re in Canada, and you want to drive across the country, you’re almost certainly passing over the Nipigon River Bridge. The bridge, which crosses the Nipigon River in Ontario, is the only way to cross between eastern and western Canada by car (at least on a road). That shouldn’t be a problem — unless the bridge needs major repairs. And in January of 2016, that happened; a winter storm stripped all the bolts from one part of the bridge, necessitating that it be shut down for 17 hours. The only way to drive across the country during that period? Leave. As the CBC reported, motorists were advised to turn back or find an “alternate route through the U.S.”

From the Archives: As the Ball Doesn’t Bounce: How San Francisco’s airport guards against earthquakes.