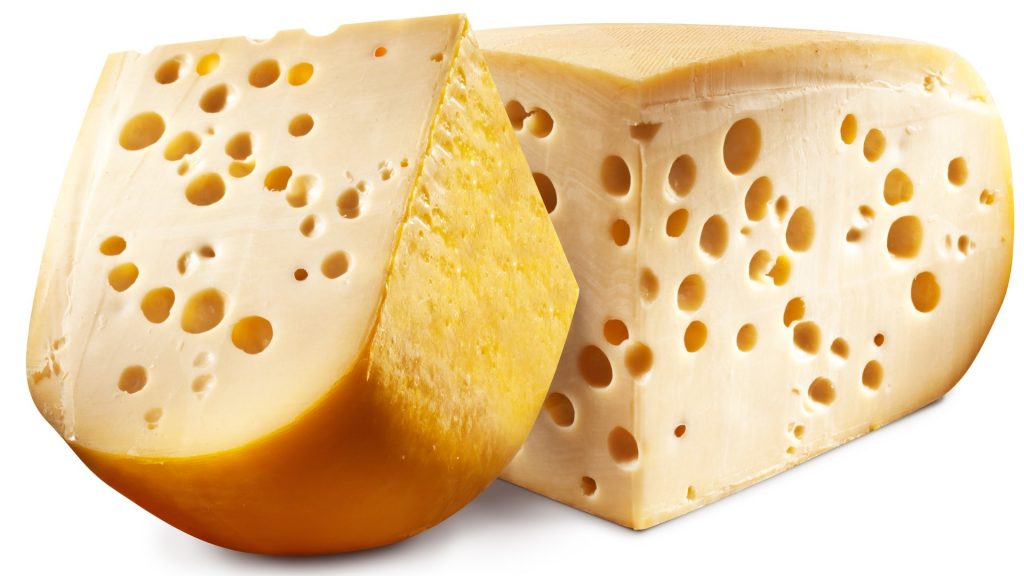

The Secret of the Swiss Cheese

Emmental cheese, probably pictured above, is supposed to come from the Emmental valley in and around Bern, Switzerland. In the United States, as a result, it’s more commonly referred to as “swiss cheese.” Like many other foods with regional names — Champagne is probably the best-known example — for cheese to be marketed as Emmental or swiss, it has to come from that region; otherwise, the label is a lie. And as swiss cheese can be sold at a premium, there’s an incentive for cheesemakers and cheese sellers alike to make “fake” swiss.

But as alluded to above, it’s not easy to tell if cheese marketed as swiss cheese is truly from Switzerland. The image above looks the part, sure, but there’s really no way to know. Even the taste isn’t a perfect indicator — while some expert tasters may be able to detect a difference, most consumers can’t distinguish between genuine swiss cheese and a good fake. And even if they could, how could swiss cheese makers prove it?

The easiest way — label the cheese — isn’t quite effective enough. According to SwissInfo, “every wheel of [swiss] cheese is already has a ‘cheese certificate’ embossed in it that has a dairy number, the guarantee of origin, the production date and a consecutive number,” and yet, counterfeiting persists. Once you remove the label or cut around that embossing, there’s simply no way for a consumer to be assured that the cheese they’re getting is what they’re paying for. So cheesemakers and the Swiss government started exploring another way: they wanted to embed the cheese itself with a secret identifier.

For years, Agroscope, a Swiss government agency focused on food and agriculture, looked for a slution. In 2008, they came up with a solution: a special type of bacteria.

As First We Feast explained, that was easier said than done. The bacteria could not “alter the smell, taste, or texture of the cheese in any way,” as that would fundamentally change the product. That takes a lot of experimentation, and those experiments take a long time: it takes months for cheese to mature; if you test too early, you may not catch any changes that will manifest later on.

Today, almost all swiss cheese — the genuine stuff, that is — has this special bacteria added to the mix at early stages. And as a result, it’s really easy to find fake swiss. As reported by Agrarforschung Schweiz, a Swiss publication focused on food and agricultural issues, you don’t need a lot of cheese to find the presence of the authenticating bacteria; “just a few grams of cheese are sufficient to identify the unique gene sequence of the marker bacteria and thus distinguish the genuine cheese from the imitation. This means that counterfeiting can also be detected in grated cheeses as well as cheese slices or rosettes.”

Of course, the mere presence of these bacterial barcodes isn’t enough to alter the authorities about any infractions. Someone has to actually do spot checks. And yes, there are cheese police who do just that. As the Globe and Mail reported in May 2011, ” Swiss [scour] stores and cheese producers at home, throughout Europe and even North America, tracking down fakes of one of their most beloved varieties, Emmentaler – best known on this side of the pond as Swiss cheese. When they find a suspicious block, they will ship it back to Switzerland for DNA testing.”