The Shape of Safety

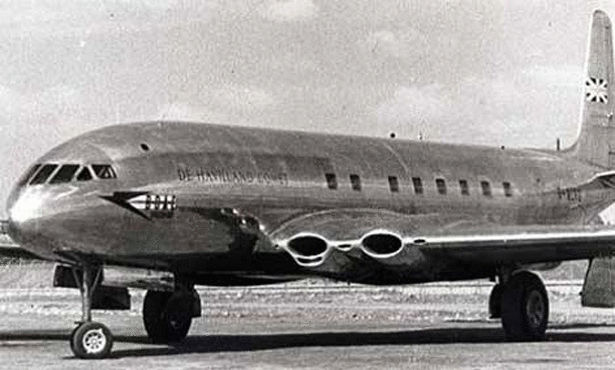

Pictured above is a prototype of the de Havilland Comet, developed in the late 1940s. It’s the first-ever commercial jet airliner, designed with a pressurized cabin. That was a pretty big leap for the technology of transportation — pressurized aircraft can fly at higher altitudes (where outside pressure is very low), allowing for smoother flights and, more importantly, lower fuel requirements.

But the de Havilland Comet’s original design didn’t last very long. In January of 1954, a Comet decompressed suddenly, causing the plane to literally fall apart in mid-air and taking the lives of all 35 on board with it. A few months later, in April, the same thing happened, this time claiming the lives of 14 people. A few other accidents predated these, originally ascribed to pilot error. But with these new accidents, an abundance of caution became warranted, and the Comet was grounded indefinitely.

In 1958, the Comet came back — a design change helped save the fleet. The problem?

The windows.

Here’s another picture of the Comet, via ExtremeTech, and you’ll note that unlike today’s commercial jets, the windows are square.

That decision, apparently, was aesthetic — the Comet’s designers thought that square windows would look nicer than rounder ones. But this proved to be a fatal mistake due to something called metal fatigue, which Wikipedia describes as “the weakening of a material caused by repeatedly applied loads.” Basically — and in defense of de Havilland’s engineers, the concept wasn’t well known at the time — the repeated pressurization and depressurization of the cabin caused stress on the hull. In most cases that wouldn’t be a problem, but the windows complicated matters. As Wikipedia further notes, the stresses were “considerably higher than had been anticipated, especially around sharp-cornered cut-outs, such as [the square] windows.” This became evident in on-ground tests using pressurized water tanks; engineers noticed that the places where the fuselage was breaking happened to be around the corners of the windows.

As a result, today, airplane windows are almost always oval-shaped — no corners means fewer points of weakness. They’re not going to give you as good of a view as their square predecessors, but they’re much, much safer.

For de Havilland, though, the fix was probably too late. The Comet, despite being first to market, became an afterthought due to its time back on the drawing board. In that interim period, Boeing developed the 707 (and shortly thereafter, McDonnell Douglas came out with the DC-8), and the Comet saw its customer base almost entirely dry up.

Bonus fact: You may have noticed something else about airplane windows — a little hole at the bottom. (Here’s a picture.) Why is it there? Once again, it has to do with air pressure. As Slate explains, airplane windows have three layers, with the innermost one acting as a barrier between us people (and everything else inside the plane) and the other two. The outer two are there for redundancy — if something were to go wrong with the outermost window, the middle one would still be there. But in order to create that fail-safe environment, engineers added what’s called a “bleed hole” to allow air to pass from the cabin to the outer window, thereby making sure that the cabin pressure is felt only by the outer window.

From the Archives: Dinner and a Backup Plan: The one person on the airplane who can’t have what the captain is having for dinner.

Take the Quiz: Which airline dominates which airport?

Related: An airplane window without a bleed hole, but it’s pretty cool anyway (because it looks real but isn’t).