The Voting Plan That Would Have Made a Difference

Today, throughout the United States, is Election Day. Millions of Americans will take to the polls today to vote on who should represent them in Congress and in thousands of other offices as well. Over the past few weeks, political organizers have tried to inspire citizens to actually exercise their right to vote. That can be a hefty task. In 2014 — that’s the last time Americans voted for federal officeholders but not in a year where there was a Presidential election — well less than 40% of eligible voters bothered to actually vote.

In this year’s election, “get out the vote” efforts have employed a relatively new tactic — the voting plan. Before election day, you’re asked to make a plan to vote — look up where your polling location is, decide what time of day you’ll get there, figure out who is going to watch your kids, etc. The theory is that if you address these factors before you actually go to vote, you’ll more likely to actually make your way to the polls when the day comes.

Whether it works or not is anyone’s guess, but it makes sense. And it would have made a ton of sense for a school board candidate name Lisa Osborn in 2011.

The city of Burton, Michigan, is located in the middle-ish of the state, not too far from Flint. As of the 2010 census, Burton claimed 29,999 residents, with Osborn being one of the almost thirty-thousand strong. Kids there attend schools in the Bentley Community Schools district, a district which is overseen by a school board of seven people elected by the city’s citizens. In 2011, two of the seats for the school board were up for grabs, and Osborn was interested in serving.

But for reasons unreported, Osborn wasn’t listed on the ballot. In fact, only one person was — an incumbent officeholder named Sofia M. Boulton. For Boulton, this was good news — with the top two vote-getters earning seats on the board, she was a shoo-in to win re-election. On May 3rd of that year, a total of 295 people checked off the box next to her name and, as expected, Boulton held onto her board seat. The second seat, though, that was a bit more complicated.

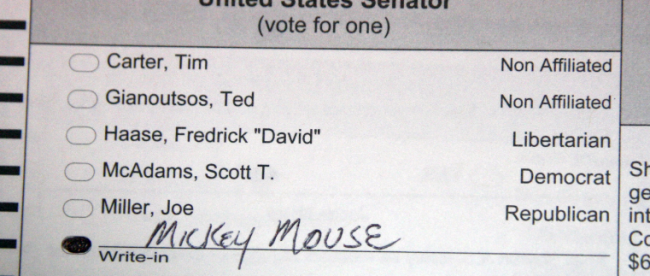

Voters cast a total of 307 ballots for school board that year; the other dozen were write-ins for people not named Sofia M. Boulton. In most systems, the person whose name appeared most often among those twelve ballots would take the other seat, but for some reason, that wasn’t true here. To win, a potential write-in candidate had to file a “declaration of intent” with the board of elections prior to April 22nd. All other write-ins were to be ignored and not tallied. And only one person had declared by that deadline — Lisa Osborn.

That put Osborn in the same position as Boulton, for all intent and purposes. She was one of only two candidates that could win, and the election was to have two winners. The only way she could lose is if no one bothered to write her name in. And given that she was an eligible voter herself, well, that wasn’t likely to happen.

But it did.

On May 3rd, while 307 other people were casting their ballots, Osborn wasn’t. Instead, she was in Flint at a baseball tournament, watching her son play. She had simply failed to plan; she took for granted that someone would bother to write her in. She told the local press, “I (thought I) would have gotten a vote [anyway]. I had plenty of people I know that would have gone up there and voted.” She, apparently, just didn’t ask any of them to do so.

Due to this oversight, the school board seat went unfilled, at least in the short term. Local rules allowed the board to appoint a town resident into the open seat and while Osborn expressed an interest in the opportunity, that went unreported. It’s unlikely that they would have, though. Per the news item above, Toby Bauldry, the board secretary at the time, was happy that Osborn wasn’t elected as “she couldn’t find the time to go and vote for herself” and therefore didn’t deserve the seat. Osborn agreed, somewhat; she called Bauldry’s take “understandable.”

So, yeah, make a voting plan — especially if you’re running for office unopposed.

Bonus fact: In Massachusetts, there’s a political body called the Governor’s Council which acts as an independent check on the state’s chief executive — the Council, per Wikipedia, “provides advice and consent in certain matters – such as judicial nominations, pardons, and commutations – to the Governor of Massachusetts.” From 1969 to 1989, a politician named Herb Connolly served on the Council. He lost re-election during the 1988 campaign when he was beaten in the Democratic primary by the conveniently named Robert B. Kennedy. (He had no relation to Robert F. Kennedy.) The vote total was 14,716 for Kennedy to 14,715 for Connolly, but it should have been a tie. On the day of the vote, Connolly spent every available moment campaigning and only got to the polls himself a few minutes after 8 PM. The problem? As the New York Times reported, the polls closed at 8; Connolly, therefore, didn’t end up voting for himself.

From the Archives: The Den of Unanimity: Meet the voter who is so isolated, that ballot box comes to him.