The Weekender: April 8, 2016

1) “Tim Urban: Inside the mind of a master procrastinator” (TED, 14 minutes and 3 seconds, February 2016). It’s a video.

So, it’s 9:36 PM ET as I write these words. This email should be hitting your inbox in less than ten hours, and I intend to sleep for at least six of those hours, hopefully more. And I have few other things I need to get done both before I go to bed and after I wake up — and I really want to put Star Wars on in the background while I write. Oh, and I don’t have Now I Know written for Monday yet; in fact, I haven’t even found a good topic yet.

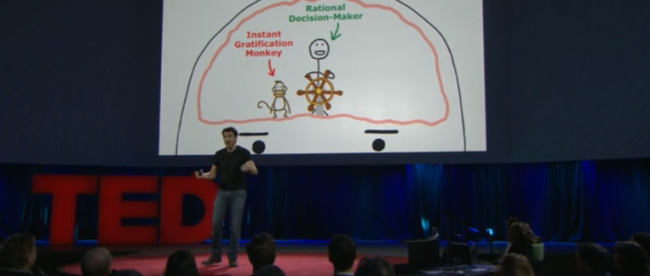

I’m a master procrastinator. If you want to kind of understand how I get things done — and I get things done, clearly, or you’d not be reading these words right now, watch the video. It’s not really who I am — I don’t pull all-nighters and my “instant gratification monkey” is more “let’s write a reddit comment about Harry Potter” than watching anything involving Justin Bieber, and I’m not terribly bad with “long-term procrastination” despite the speaker’s observation, but the point otherwise holds.

Oh, and his blog, Wait But Why, is pretty great.

2) From the archives: McLeaned Him Out: On April 9, 1865, the Civil War ended right where it began — at Wilmer McLean’s house. That’s because Wilmer McLean was a really unlucky guy, though. (You’ll see.)

3) “How a Ragtag Gang of Retirees Pulled Off the Biggest Jewel Heist in British History” (Vanity Fair, 40 minutes, March 2016). This will be a movie someday.

It required a team with diverse skills…. It took ingenuity and brute force,” reporter Declan Lawn speculated on BBC television three weeks after what was already being called “the greatest heist in British history,” the audacious April 2015 ransacking of safe-deposit boxes in Hatton Garden, London’s diamond district. The crime was indeed epic. So much cash, jewelry, and other valuables had been taken that the loot, worth up to $300 million according to estimates at the time, had been hauled out of the vault in giant trash containers on wheels. Lawn demonstrated the acrobatic feats the gang must have used, and London’s newspapers were filled with artists’ renderings of the heist, featuring hard-bodied burglars in black turtlenecks doing superhuman things. Experts insisted that the heist was the work of a foreign team of navy-SEAL-like professionals, likely from the infamous Pink Panthers, a Serbian gang of master diamond thieves. Retired Scotland Yard detective Barry Phillips believed it was the work of a highly technical team, assembled by a so-called “Draftsman”—who financed the heist and assembled the players, probably from the U.K. He speculated that no member of the gang would have known any of the others, in order to preserve “sterile corridors,” making it impossible for any perpetrator to rat out the others.

[ . . . ]

The Hatton Garden heist, it turned out, had been the work of [a] ragtag group of superannuated criminals representing the last of “traditional British villainy,” in the words of the police commander, Spindler. Most were in their 60s and 70s—more Lavender Hill Mob than James Bond. “Run? Ah, they can barely walk,” Danny Jones wrote to Sky News reporter Martin Brunt from jail. “One has cancer—he’s 76. Another, heart condition, 68. Another, 75, can’t remember his name. Sixty-year-old with two new hips and knees. Crohn’s disease. I won’t go on. It’s a joke.”

Yet they had defied age, physical infirmities, burglar alarms, and even Scotland Yard to power their way through walls of concrete and solid steel and haul away a prize now estimated at more than $20 million—at least $15 million of which is still missing.

4) “The Itch” (New Yorker, 28 minutes, June 2008). We don’t really know all that much about why we itch. Case in point? A woman’s head itched so much she kept scratching, until she hit her brain. If you can stomach this article, it’s fascinating. Thanks to reader Colleen W. for sharing it with me.

WeekenderAdUnits

5) “The Baseball Card Bubble” (The Economist, 12 minutes, December 2014). The subhead: “How a children’s hobby turned into a classic financial mania.” And yes, for those who know to ask the question, I still have a 1989 Upper Deck Ken Griffey Jr. card at my parents house.

In 1979, when Mr Beckett published his first official price guide, the 1963 rookie card for Pete Rose (the all-time Major League Baseball hits leader) was valued at $5, while the 1973 rookie card for Mike Schmidt, a Hall of Fame third baseman, went for 12 cents. Just five years later, when Mr Beckett’s guide went monthly, those values had risen to $350 and $65 respectively. In 1994, at the top of the market, the cards purportedly fetched $1,100 and $425. Among high-value cards the rise in prices in the decade to 1994 was on a par with equity-price increases in the ten years to 2000 and home-price gains in the decade to 2006.

Cards went for outrageous sums; and, as always happens in bubbles, people who had shared only a passing interest in the hobby found themselves buying with aplomb, for fear of looking like suckers later for having missed the obvious route to wealth. For a few strange years, children—like your correspondent and his similarly crazed brothers—piled up boxes full of cardboard, confident that their contents would only grow in value, never quite asking themselves who would buy their hoards, but never doubting that someone would.

6) “The Doomsday Scam” (New York Times Magazine, 20 minutes, November 2015). The subhead: “For decades, aspiring bomb makers — including ISIS — have desperately tried to get their hands on a lethal substance called red mercury. There’s a reason that they never have.” (You can probably guess why not, but it’s interesting anyway.)

Have a great weekend!