The “You Should Retire” Law of 1882

In the United States, the Supreme Court is the highest legal authority in the land. So you’d expect that its constituent members — the nine Justices who serve on the Court — to be pretty famous people. But by and large, they’re not. In 2012, for example, FindLaw.com released survey results that found that “only 34 percent of Americans can name any member of the nation’s highest court.” Even worse, per a 2016 study (pdf), “nearly 10% [of those they surveyed] say that Judith Sheindlin—“[TV’s] Judge Judy”—is on the Supreme Court.” Fame and Supreme Court membership simply do not go hand in hand.

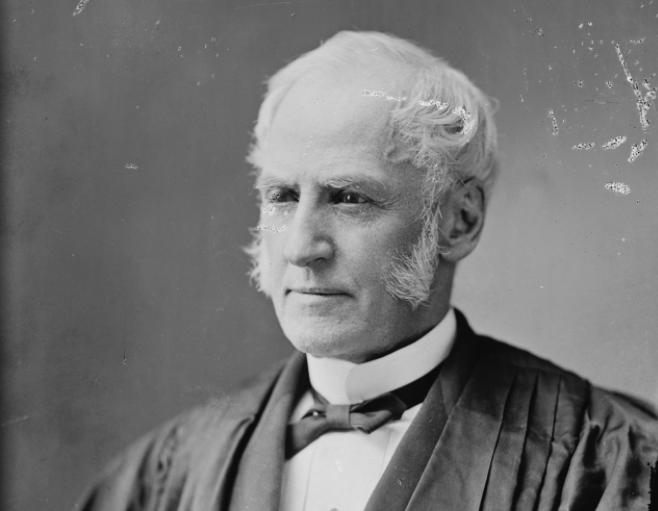

So if you’ve never heard of Ward Hunt (above), you’re probably not alone. Hunt served on the Supreme Court from December 11, 1872 until January 27, 1882, giving him just over nine years of service. His not-quite-ten-year tenure on the federal bench wasn’t all that impactful; here’s what the Supreme Court Historical Society has to say about it:

President Ulysses S. Grant nominated Hunt to the Supreme Court of the United States on December 3, 1872. The Senate confirmed the appointment on December 11, 1872. Hunt served on the Supreme Court for nine years and retired from the Court in 1882. He died on March 24, 1886, at the age of seventy-five.

“Not much” would be an overstatement. There’s literally nothing mentioned. And that’s probably rather fair. Hunt’s most notable moment as a Justice came when he was handling a criminal case — he presided over the trial of Susan B. Anthony in 1873. Anthony had famously tried to vote, despite being ineligible to do so, Hunt ruled that she was not entitled to a trial by jury (his opinion was that everyone agreed on the facts, so there was no need) and found her guilty of violating the law. But as he was acting more like a regular trial judge in that case than a Supreme Court Justice, that’s typically not mentioned as part of his work on the Court. When it came to actual Supreme Court decisions, he’s probably best known for writing a dissenting opinion in Pennoyer v. Neff, and given that most of you have never heard of Pennoyer v. Neff, it’s probably fair to say that the Supreme Court Historical Society did a reasonably good job encapsulating Hunt’s work.

But there’s something significant that biographical snipped leaves out. Part of the reason that Hunt’s impact on the Court was so small is that he, effectively, stopped working about halfway through his time on the bench. As Constitutional Law Reporter explains, “In 1878, Hunt suffered a stroke, leaving him paralyzed. The severity of the stroke prevented him from attending court sessions or rendering opinions, yet Hunt remained on the Court for three more years until his retirement on January 27, 1882.”

While not Hunt’s fault — a debilitating stroke isn’t something one intentionally brings upon themselves — the fact remains that he effectively stopped coming to work for three or four years. In most normal employment situations, he would have been fired for his absenteeism, but federal judgeships aren’t like normal jobs. As the official site of the United States Court explains, “Article III [of the United States Constitution] states that these judges ‘hold their office during good behavior,’ which means they have a lifetime appointment, except under very limited circumstances. Article III judges can be removed from office only through impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate.” And it’s not clear that being disabled by a stroke is something that impeachment and conviction can address.

And it’s something that shouldn’t have been necessary anyway. When Hunt had his stroke, he was in his late 60s and his job, like any other, helped him afford his lifestyle. Being unable to work was bad and as the Biographical Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court explained, “Hunt lacked an independent income.” If he retired from the Court, he’d also be unable to find a new way to earn a living. The good news was that he was entitled to a federal pension, but the bad news was that the pension only vested with ten years of service — and when he had the stroke, he wasn’t all that close to hitting that milestone. So Hunt, needing a way to make ends meet, didn’t retire.

After Congress realized this was the problem, they fixed it — well, sooner or later. As Jrank explains, “three years after his stroke, Congress passed a special retirement bill that gave Hunt a pension if he agreed to resign within thirty days. Hunt resigned in January 1882, on the day the bill became law” (and eleven months before his ten-year anniversary).

Bonus fact: Despite Hunt’s ruling in the Anthony case, defendants in criminal trials are guaranteed a trial by jury if they so request. But there’s no requirement that the jurors not be on drugs — kind of. In the 1987 case Tanner v. United States, a juror gave testimony that some of the other jurors were drinking heavily, smoking marijuana, and doing cocaine. The Court ruled that while that may not be a good thing, it doesn’t matter — courts are “prohibited [from using] of juror testimony to impeach a jury verdict,” and therefore, justice had to be blind toward the jurors’ drug and alcohol use.

From the Archives: What to Call Witnesses, According to the Supreme Court: Calling her “Mary” isn’t going to work.