Too Much of a Good Thing

By and large, modern societies (especially Western ones) protect historical landmarks from the whims of individuals. While these buildings, over time, often find themselves owned by private individuals or corporations, these protection laws prevent the owners from haphazardly renovating or destroying these architectural pieces of history. After all, a building with historical significance in the middle of an bustling urban center may not be worth all that much to the owner, but the land it’s sitting on sure would be.

On the other hand, owning a historical landmark can be a very good thing — because of the tourists it can attract. But too many tourists? That may sound like a good business, but to some, it’s a pretty big annoyance. Which is in part why William Shakespeare’s final home no longer exists.

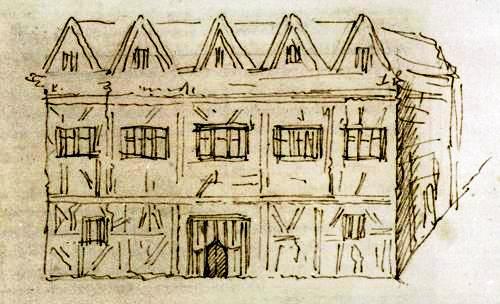

Shakespeare was born in 1564 in the English town of Stratford-upon-Avon, but did not find success until he moved to London in his late teens or early 20s. By his early 30s, however, he was already considering what to do in his retirement. His son, Hamnet, had recently died, and in 1597, Shakespeare purchased a home in Stratford-upon-Avon called “New Place,” a sketch (from 1737) of which is above. In 1610, he and his family moved into New Place, which would become Shakespeare’s last residence; he died in 1616.

New Place was originally built in the late 1400s by a merchant named Hugh Clopton. The house was probably something Shakespeare took notice of growing up, as it is now known to have been one of the largest homes in the town at the time. Shakespeare’s daughter Suzanne inherited the house after his wife Anne’s death in 1623, and Suzanne, in turn, bequeathed it to her daughter Elizabeth. Elizabeth ended up marrying Thomas Nash, literally the boy next door. When Elizabeth died, for some reason (perhaps because Elizabeth abandoned it to move next door, although that’s pure conjecture), Hugh Clopton’s heirs took ownership of New Place. One of Clopton’s heirs restored the house and in time, sold it to a reverend by the name of Francis Gastrell in the mid-1700s.

By 1753, Shakespeare’s fame had grown far and wide, and Gastrell’s home became a well-known tourist attraction. Even a mulberry tree, allegedly planted by the Bard of Avon himself, was the subject of interest from transient visitors. Gastrell, however, wasn’t looking to sell tickets to people who wanted to peek in his bedrooms or trample his garden; if anything, as the BBC notes, he found these visitors unwelcome and annoying. So he chopped down the mulberry tree.

This, of course, made the problem worse. Townspeople and tourists alike retaliated, throwing rocks through New Place’s windows (which seems like a silly way to protest against the destruction of a historical landmark). The town government stepped in — but not in Gastrell’s favor. It declined Gastrell’s request to expand New Place’s garden and upped his taxes. In 1759, Gastrell fought back:

He burned the house down.

Gastrell left Stratford-upon-Avon soon after, becoming a persona non grata after destroying the last home of William Shakespeare (and besides, it’s not like he could still live in the rubble and empty foundation into which he turned New Place). In 1891, the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust (which was established in 1846 to buy the Bard’s childhood home, in part to prevent U.S. showman P.T. Barnum from buying it and shipping it, “brick-by-brick,” to the States), purchased both the remnants of New Place as well as Thomas Nash’s home. The site is now open to tourists, without threat of further destruction.

Bonus fact: The term “too much of a good thing” was originated by Shakespeare. He first coined it in the play As You Like It.

From the Archives: Building, Apart: A house in China which defied demolition.

Related: An antique print of New Place, purporting to be from 1855, which (given the above) is strange.