When People Were Afraid of Parrots

If you’re running a business, it’s very important that your customers feel safe before dealing with you. If they don’t, you’re not very likely to get their patronage. Amusement parks that get a reputation for injuring their guests tend to shut down. Restaurants that have an outbreak of food poisoning find themselves bereft of future diners. LEGO stores with no-shoes policies probably won’t have many visitors. And then there was the most dangerous of the lot — pet stores that sold parrots.

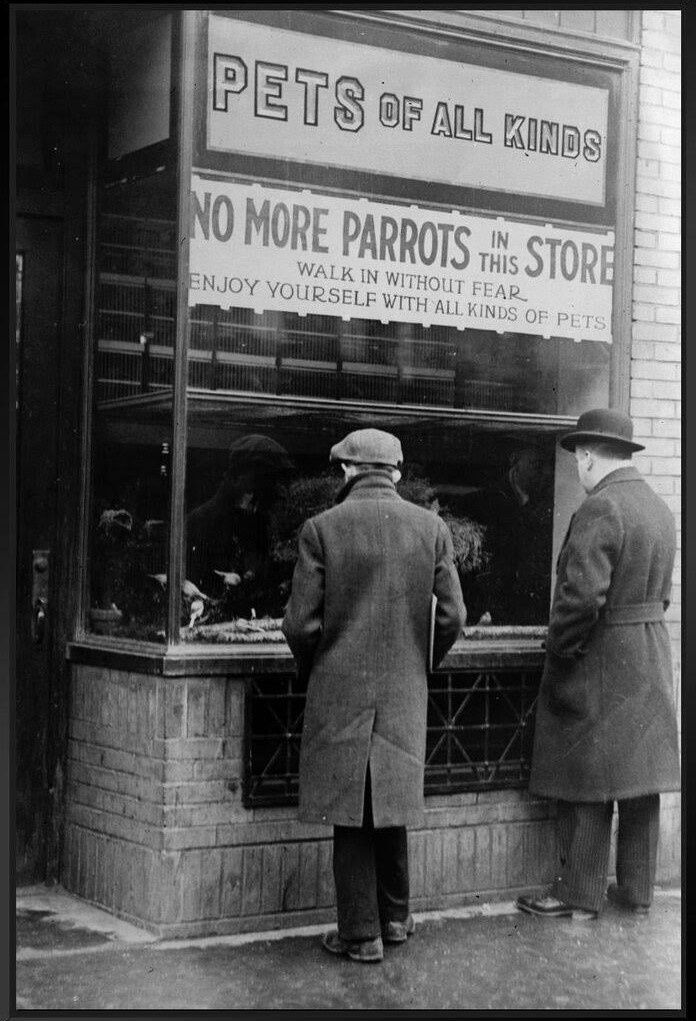

Well, not today. But in 1930, that was definitely the case, as seen in the image below.

The photo above shows a pet store from that year. The big sign reads “Pets of All Kinds,” but the smaller sign beneath it carves out an exception. It states that there are “no more parrots in this store” and that customers can “walk in without fear” and “enjoy yourself with all kinds of pets” (other than parrots, implicitly.) The store could not be more clear: if you want a dog, cat, rabbit, or even an iguana, you’re probably in luck, but if you want a parrot, you’re in the wrong place.

Parrots are perhaps most well known for their ability to repeat what humans say; the word “parroting,” which means “to repeat exactly what someone else says, without understanding it or thinking about its meaning,” comes from that trait. And throughout history, there are lots and lots of examples of parrots repeating language with problematic results — they’ve engaged in swearing fights, tattled on cheating girlfriends, etc. But in this case, the issue isn’t what parrots said — it was with what they spewed. Specifically, parrots were connected to a disease called psittacosis, or “parrot fever.” And it was deadly to humans.

The problem with parrots began on Christmas Day, 1929, just weeks after the stock market crash that sparked the Great Depression. As historian Jill Lepore told NPR, a Maryland man named Simon Martin had given his wife a parrot for Christmas, but when it came time to open the presents, the parrot was dead. That was strange, as parrots tend to have long lives. Money was tight, so Martin took the dead parrot back to the pet store and was given a replacement bird. Unfortunately, the dead bird wasn’t the Martin family’s biggest problem. Per Lepore, “Martin’s wife Lillian and his daughter and son-in-law become quite sick within a matter of days, quite dangerously sick.”

The Martin family’s doctor had just read about psittacosis a few days or weeks earlier and immediately made the connection between the dead bird and his unusually ill patients. He and Mr. Martin (who served in the local Chamber of Commerce) alerted the local government, which began investigating. The pet store in question had sold dozens of other birds, and a trail of illness followed. Not only were many of the birds sick, but so were some of the store’s employees; four of them, per Lepore, came down with symptoms in early January.

This was a big problem because medical science at the time didn’t have a reliable treatment for the disease. Mental Floss explains:

Caused by the bacteria Chlamydia psittaci, parrot fever (or psittacosis) can be contracted after coming into close contact with infected parrots, pigeons, ducks, gulls, chickens, turkeys, and dozens of other bird species. The symptoms resemble pneumonia or typhoid fever, with victims suffering from extremely low white blood cell counts, high fevers, pounding headaches, and respiratory problems. Today the disease can be treated with antibiotics, but in 1930, 20 percent of victims were expected to die.

Without a cure at hand, public health officials began asking around. Charles Armstrong, a pathologist for the U.S. Public Health Service at the time, led the efforts by calling everyone and anyone who could have a clue on how to stop the spread of parrot fever. And while that strategy was both obvious and correct, it had a downside: fear of psittacosis spread faster than the fever itself. People avoided parrots like the plague, which made a lot of sense given that some of the birds were carrying something similar to the plague. And the problem ultimately became one of national concern; toward the end of January, per Mental Floss, “President Herbert Hoover [issued] an executive order stating that ‘No parrot may be introduced into the United States or any of its possessions or dependencies from any foreign port.’”

The parrot fever panic probably saved lives. While we don’t have a precise number of psittacosis cases from the period, our best estimates suggest that only about 750 to 800 people were infected by the underlying bacteria, likely due to the quick and dramatic reaction to the outbreak (and the fact that it doesn’t spread well from human to human). Unfortunately, the mortality rate proved to be roughly true: parrot fever claimed more than 100 lives in 1930 alone.

But before the year was out, the parrot panic almost entirely subsided. Cases dwindled and America’s collective aversion to squawking birds diminished. In November of 1930, Hoover lifted his ban. And by Christmas, some pet stores began selling parrots once again.

Bonus fact: A year after the parrot pandemic, parrot blood played a role in helping a young girl recover… kind of. In 1931, a 15-year-old girl named Lillian Fisher was struck by polio and was sent to a hospital in Illinois. The doctors called her regular physician, who told them to give Fisher a transfusion of her parents’ blood, but the hospital doc — who later claimed that the phone connection wasn’t great — misheard the instruction and thought he said “parrot’s blood.” Per the United Press, the doctor “sought frantically for a parrot, finally found one, and [ultimately] transferred [its blood] into the girl’s veins.” The girl recovered, but all the doctors involved credited that to coincidence, not parrot blood.

From the Archives: Polly’s Neighbor Want a Walnut?: Parrots may get their owners in trouble (for repeating things more than spreading disease), but they’re also good sharers — at least, with other parrots.