Where Everybody Knows Your 6E 61 6D 65

On September 20, 1982, an unnamed Bostonian teenager purporting to be First Sergeant Walter Keller walked into a below-grade bar in Boston, Massachusettes, and ordered a beer. The barkeeper checked his ID and noticed that Sgt. Keller was 38 years old and likely served in Vietnam, and asked “Keller” what it was like serving over there. “Keller” replied that it was “gross” and the barman joked “That’s what they say, ‘War is gross’” and declined to serve the teenager and his obvious fake ID. Despite not actually getting his beer, the young man is typically considered the first patron in that bar’s history.

You can watch the whole exchange here, because that’s how “Cheers,” the famed sitcom, began. Eleven seasons and an additional 274 episodes later, the series has become a touchstone of American television, even thirty years since it closed its doors for good.

Even if you’re a fan of the show, probably don’t remember the fake Sgt. Keller — he was credited as “Boy” — but you almost certainly can name a few of Sam Malone’s patrons over the course of the show. Frazier Crane, the psychiatrist, ended up with his own spinoff, for example. But he joined the show in its third season. The two mainstays from day one were Norm Peterson, a sometimes-employed accountant and Cliff Clavin, a know-it-all postal worker. Despite Cliff’s abuse of trivia — it should be fun, not annoying!! — the two characters became a popular duo with fans near and far.

Which led to a very strange lawsuit involving robots.

Toward the end of the 1980s, Cheers’ popularity led Paramount, the studio behind the show, to find more ways to make money beyond distribution rights and advertising. As VinePair explains, “Paramount licensed the ‘Cheers’ name to retail products like Bloody Mary mix, and to Vegas slot machines. It also issued a merchandising license, in 1989, to the Bull & Finch Pub in Boston, whose exterior had long been used as an establishing shot for the TV series.” And those, too, were successes — and they were not alone. A company called Host International struck a deal to bring a Cheers-inspired bar experience to airports across the United States (and one in New Zealand), believing that people who would like to get away needed a place to hang out before their planes took off.

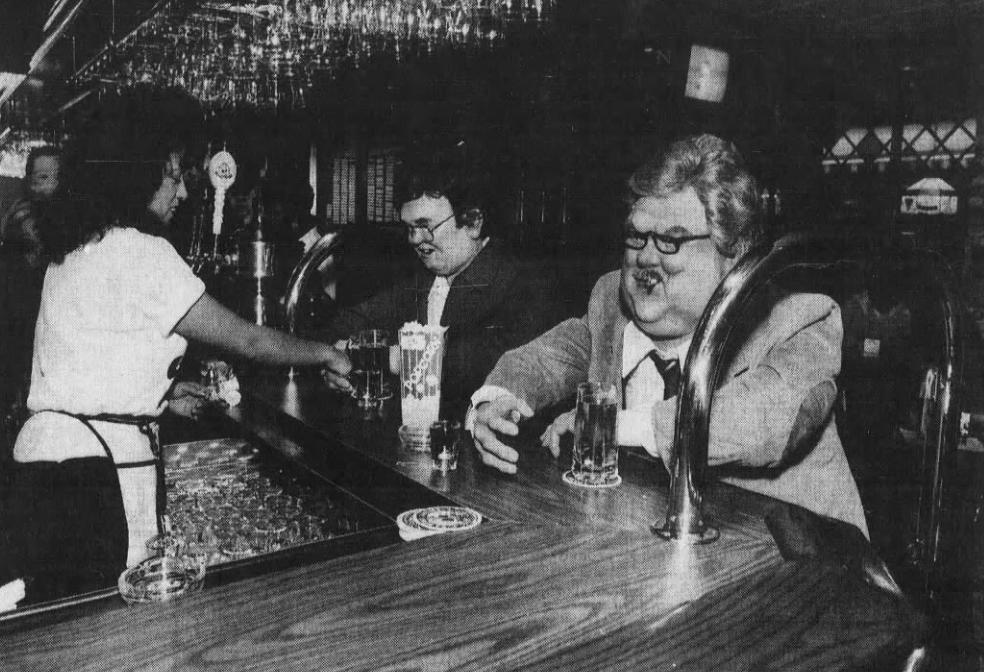

These airport bars were also successful, in large part because they brought the Cheers experience to life. Per VinePair, “They outfitted both spaces with a signature square bar surrounded by round, no-back stools. On their walls, a framed Red Sox jersey once “worn” by Ted Danson’s Sam Malone character. Near the entrances stood an iconic cigar-store Indian and a Wurlitzer jukebox. Staff was even required to pass an acting class, perhaps even affect a “Bawston” accent, which they would use to perform for customers.” And then, they added customers — a pair of animatronic barflies that, per Variety, were “supposed to look like Norm and Cliff. These robots move and even banter back and forth, much in the same manner as Norm and Cliff.” You can see a photo of the machines below (via the Detroit Free Press) and the resemblance is far from uncanny, but again, we’re talking about robots from the 1980s built for an airport bar, so some flexibility is warranted.

These robots were named Hank and Bob, not Cliff and Norm, but regardless, everyone who went to the fake Cheers installations knew the robopatrons’ real names. The animatronics were there with Paramount’s permission, but George Wendt and John Ratzenberger, the actors who played Norm and Cliff, respectively, weren’t privy to or a party to the agreement. And they weren’t fans of the machines, or, at least, they weren’t happy that they didn’t get paid. So Wendt and Ratzenberger sued.

At first, the courts found in favor of Host and Paramount; per Mental Floss, “a federal judge in Los Angeles dismissed the suit, stating that the robots bore little resemblance to the actors.”But that decision was reversed on appeal. Undaunted, the studio and restaurateur duo appealed again, and ultimately, asked the Supreme Court to weigh in. As the Chicago Tribune noted in October of 2000 — nearly seven years after the real Cheers (well, the TV show version) closed its doors — the Supreme Court ruled without comment that the appellate decision should stand and that Wendt and Ratzenberger could bring their case in front of a jury.

Sadly, it never got that far. The two sides settled in 2001. And even more sadly, the Cheers airport bars no longer exist.

Bonus fact: After “Cheers” went off the air, the sitcom “Frasier” debuted — a spinoff centered on Cheers customer Frasier Crane. Each of the surviving members of the main Cheers cast made a guest appearance except for one. Kristie Alley, who played Rebecca on Cheers, did not want to be part of the show. Screen Rant explains why: “The decision was a personal choice from the actress that stemmed from being a member of the Church of Scientology; Alley was raised as a Methodist but became a Scientologist in 1979 and remains one to this day. Before she was even invited to make an appearance on Frasier, Alley announced that there’s no way that she’s partaking in the project as recalled by co-creator and executive producer David Lee. This was because the sitcom centered on the medical practices of psychiatrists Frasier and Niles Crane (David Hyde Pierce) — a field Scientologists do not believe in it. According to Lee, he wryly responded ‘I don’t recall asking.’”

From the Archives: Bad Molasses: I’ve never written about Cheers before so here’s a story about Boston.