Why 19th Century Britons Lost Their Heads

If you spend enough time on TikTok today, you’ll find a bunch of kids ages 13-24 covering their pets in whipped cream and teaching them how to dance the Macarena, a song that those teens and young adults hadn’t heard of before and attribute to the era of Mozart. Then, using TikTok’s video editing software, these young content creators add effects that make it look like their dogs and cats are actually singing along to the lyrics and are actually on the Moon. The trend has gotten so popular that some of the more skilled Whipped Macarena Moon Dog video makers are selling their services as creators-for-hire, so if you want your own such video, you can have one made for the very reasonable price of $29.99.

Actually — none of the above is true. I made it up. But it could be true, right? Social media, meme culture, and the like have definitely made for some very weird trends over the past decade or so. Things like Whipped Macarena Moon Dogs are products of our modern world, right?

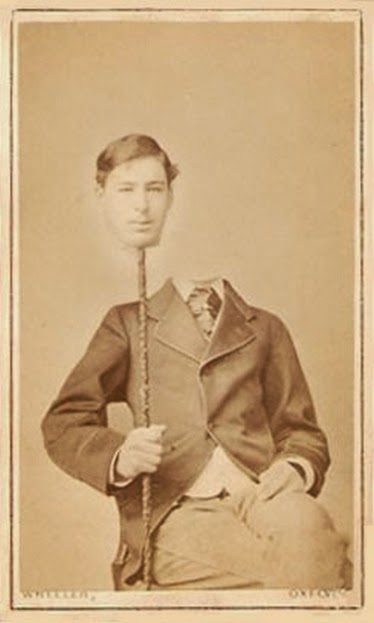

Not quite. Humans have gotten weird in front of cameras for as long as cameras have been readily available. The proof? Here’s a picture of a British man from 1875 named William Henry Wheeler, and as you can see, his head isn’t squarely on his shoulders. Literally.

And what makes that picture even more interesting is that it isn’t unique. Not even remotely so.

The trend — known as “Victorian Headless Portraits ”— began in the late 1850s. (To give a sense of the time scale here, that’s before the start of the American Civil War.) Most experts believe the trend got its start when photographer Oscar Gustave Rejlander’s “Head of St. John the Baptist in a Charger” (seen here) gained popularity toward the end of the decade, but like most trends today, that’s not wholly clear. Regardless, over the next few decades, others gained an interest in Rejlander’s methods. He pioneered a photographic merging technique called “compositing” where he’d take multiple photographs and, by hand and over weeks at a time, would combine their negatives into one image and then develop that composited image as if it were a single-shot photograph. As History Facts explained, all you really needed to make a photo like the one above was glue and time: “To achieve this illusion, the subject would pose as multiple images were captured depicting the body and head making various gestures and expressions. The photographer would then take those images and cut out a head from one and paste it on another, resulting in one or several headless photos that appeared to be captured in one take.”

And many, many people wanted pictures of themselves doing the impossible. There are many examples (like these) of people holding their own heads, of heads floating unmoored in thin air, and of more macabre scenes involving knives and terrorized looks on people’s faces. Regular people didn’t think it was weird — in fact, most people thought it was cool. So cool, that they wanted one for themselves.

But that was easier said than done. The people of late 19th century England didn’t have iPhones, Photoshop, or any of the modern tools used to make such things today. So if you wanted a headless portrait, you needed to either buy yourself a camera — which was prohibitively expensive for hobbyists — or hire a photographer. The latter is exactly what happened. Photographers began advertising their services in case you wanted a picture of yourself doing the impossible. For example, Samuel Kay Balbirnie, a photographer in Brighton, England, took out an ad (the text of which can be found here) that touted his services in creating “Ladies and Gentleman taken showing their heads floating in the air or in their laps.” (Balbirnie also offered “spirit photographs” which he described as pictures “taken floating in the air – in company with tables, chairs and musical instruments,” and “dwarf and giant photographs” noting that “the former [was] very ludicrous.”)

The fad fizzled in the early 1900s for no obvious reason, much like the modern social media trends we experience today. Thankfully, the trend died before anyone involved in it did; there are no reports of anyone actually cutting off their own head in an effort to get a headless photo.

Bonus fact: The Victorian headless photographs were all in good fun, but some trends were, well, not. As the BBC reported, “death portraiture” — the act of taking a photo of someone recently deceased as if they were still alive — was common in the late 1800s. (That link has a lot of examples if you want to see them, but be warned: they’re creepy.) The impetus for the trend was a surge of fatal childhood diseases such as measles and rubella; as the BBC notes, after death “was often the first time families thought of having a photograph taken — it was the last chance to have a permanent likeness of a beloved child.” As healthcare, particularly for children, improved, the need for such photos waned, and the trend disappeared.

From the Archives: Invisible Mothers: How 19th-century portrait photographers took pictures of babies. Also, Fredrick Douglass Is Not Amused: Why Fredrick Douglass, the most photographed American during the 19th century, didn’t smile for the camera. Ever.