Why Isn’t This Tennis Ball Bouncing?

On January 21, 2011, Maria Sharapova and Julia Goerges faced off in the Australian Open. Sharapova won in three sets, 4-6, 6-4, 6-4. But physics, not tennis, was the story of the day.

Why? Tennis balls, by design, bounce. That’s a really important part of their function. But as seen below, sometimes that doesn’t happen.

(Here’s a video version of that image doesn’t animate.)

During warmups, Sharapova noticed that something was amiss — a small but not insignificant soft patch, which, “at first, she thought the cushioning in her left shoe was behaving oddly or that some extra padding had somehow been added to the court,” per ESPN. She called over a court official, and then what you can see above happened next. The official walked over with a ball, tossed it gently at the court below, and the ball just kind of stuck there as if it forgot it was a tennis ball.

While this apparent violation of the laws of physics was mystifying for fans, the Open staff knew exactly what had happened — and how to fix it.

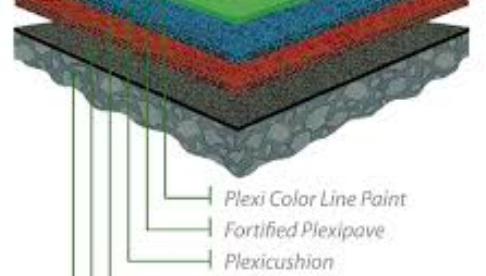

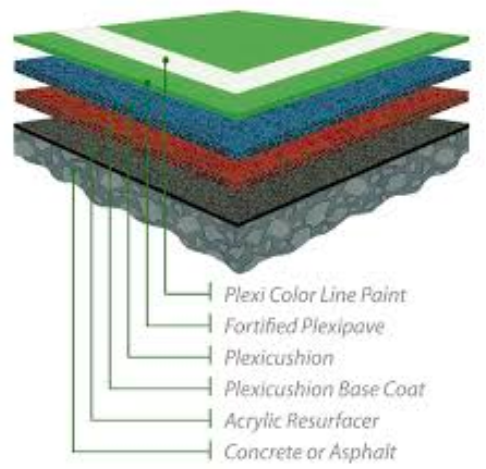

Tennis courts come in a variety of surfaces. Wimbledon is held on grass courts, the French Open on clay, and the U.S. Open and the Australian on hard courts. Hard courts, though, aren’t just painted concrete. Here’s a cross-section of some of the layers on some hard courts, and as you’ll see, there’s a lot going on there.

While that may not be the actual formulation used at the Australian Open, it’s representative and helps us understand the mystery here. The mix of materials below the surface serves a lot of purposes — they somewhat reduce the stress on the knees and legs of the players, they help ensure a consistent bounce (usually) from the tennis balls, and they help keep the courts in good condition despite the fact that the courts are exposed to the elements.

But sometimes, things go wrong — as it did before the Sharapova/Goerges match. ESPN explained: “Moisture from recent rains had gathered under the court’s Plexicushion layer, evaporated as temperatures rose Friday and caused a pocket of vapor that lifted part of the surface.” The lifted area was, therefore, cushioned. The ball, instead of bouncing off a hard surface, fell asleep on a pillowy one.

The short-term fix was pretty simple, though — someone from the grounds crew came by and drilled a couple of tiny holes near the vapor pocket, allowing the gas to escape and the cushion to dissipate. And a permanent fix may have been rather straightforward, too. NPR presumes that, later in the day, glue was injected in the holes to help the layers stick together. And the game went on, otherwise unabated by mysteries of science.

Bonus fact: Many tennis players, including Sharapova, make a grunting noise when they strike the ball during matches. (Sharapova’s is particularly loud; per the Telegraph, she hits volumes as high as 109 decibels, which is “only slightly quieter than a chainsaw.”) And it may make them better tennis players. As CNN reports, “Ten players from the US top tier Division I — five men and five women — were placed in different groups. One group was told to grunt while the other wasn’t. The grunters, in a combined hitting session of 20 minutes, registered increased velocity of 3.8%.” Researchers attribute the increase to improved breathing which better leverages one’s core muscles.

From the Archives: Tennis Shoes: The tale of a last-minute champion.