Why Only Dead People Are On American Money

Pictured above is a $1 bill. It features, pictured in the center, an image of George Washington, the first President of the United States. The bill’s design hasn’t meaningfully changed in nearly a century and isn’t likely to change in the near future, either. (Here’s a Now I Know from 2019 explaining why). But if for some reason it does, one thing is for sure: if George Washington’s face is replaced by that of another person, the person depicted will have been long dead.

Why? Because of a guy named Spencer M. Clark.

America was embroiled in a civil war in the early 1860s, and that war created a massive metal shortage. A lack of metal made it hard for the U.S. Treasury to mint coins, and coins were important — perhaps more so than today. The American economy couldn’t just round everything up to the nearest dollar — almost all common purchases at the time cost way, way less than a buck. So the government began issuing “fractional currency” — basically, paper money with the same value as the coins that the treasury could no longer afford to mint. Congress authorized the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to create fractional currency notes worth 3, 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50 cents.

As those fractional currency notes didn’t exist yet, the Bureau needed to create brand new designs. But it wasn’t clear whose job it was to approve any such designs, or if the Bureau had any guidance given to them about who, if anyone, should be depicted on these notes. Without such clear direction, the matter fell to Spencer M. Clark, the Superintendant of the National Currency Bureau — basically, a middle manager working in the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

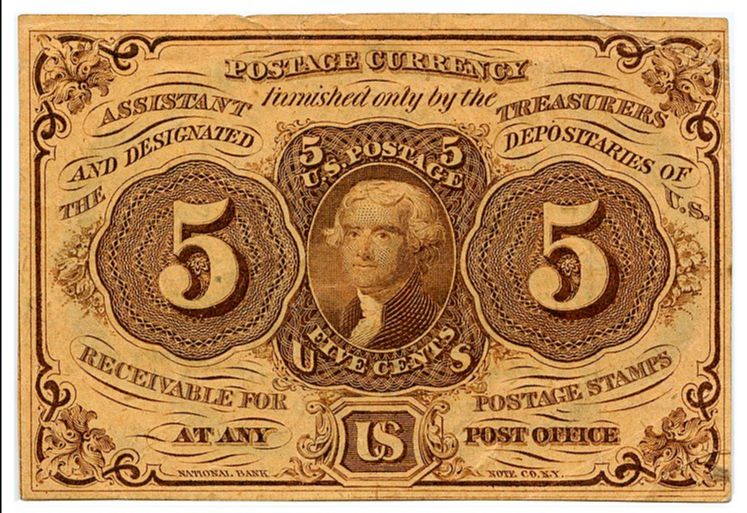

Here’s the 5-cent fractional note he and his team designed, printed, and issued in August of 1862:

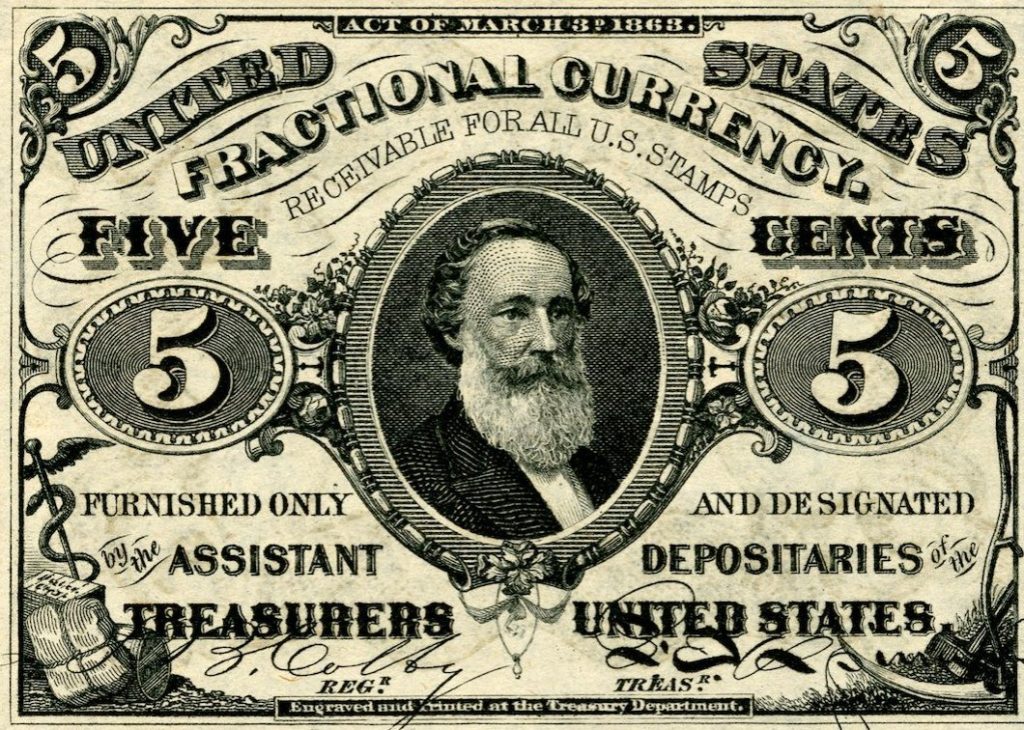

Not a bad design, right? Too many words, sure, and it talks about postage stamps a lot (which is its own story, not important for today’s purposes), but it feels legitimate. The guy pictured in the center is Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States and a Founding Father — a perfectly reasonable choice for mid-19th century currency. Those remained in print for about a year, but in October of 1863, the Treasury decided to issue another round of fractional notes — and for reasons unclear, ordered a new design. So Clark and team got back to work, and this time decided to feature George Washington on the paper nickel. (Here’s what that 5-cent note looked like.) And finally, in December of 1864, the Treasurer ordered yet another design for the 5-cent note. This was the end result that Spencer M. Clark came up with:

Don’t recognize that man? No, he’s not a former American President, nor anyone else famous. That’s a picture of Spencer M. Clark. The mid-level manager in charge of currency design put himself on America’s newest currency.

How he got away with this is unclear. According to Atlas Obscura, “Congress had asked for the note to honor William Clark of the Lewis and Clark explorations,” but that’s not William Clark (or Meriweather Lewis, for that matter). But the instruction was vague; instead of spelling out “William Clark,” Congress simply said “Clark.” According to other sources, there was no such direction given by Congress, and Spencer M. Clark simply put himself on the 5-cent note because he could. Either way, when these bills started making their way into circulation, many members of Congress noticed — and they weren’t pleased.

What Clark did wasn’t illegal and may not have been unethical; per some accounts, he cleared the decision with the Treasurer of the United States, Francis E. Spinner, who himself was depicted on the 50-cent note. (Spinner’s inclusion on American money isn’t all that ridiculous; every dollar bill now in print bears the signature of the Treasurer of the United States. And Spinner’s decision to okay Clark’s ruse may have been innocent; per Wikipedia’s editors, Spinner likely thought that Clark was making a reference to a high-level Treasure Department leader, Freeman Clarke, the Comptroller of the Currency.) But Congress didn’t want this to ever happen again. Martin Thayer, a representative from Pennslyvania, was particularly incensed and drafted legislation banning the depiction of anyone living on currency going forward. The Thayer Amendment became law in April 1866, only about a year and a half after the Clark notes came into circulation.

The Clark-bearing 5-cent notes are collectors’ items today, but only because they’re old, not because they’re rare. The Thayer Amendment barred the image of living people on future currency but didn’t actually require the Treasury to replace the note with Clark’s face on it. Those remained in print for about two years and only stopped being issued because Congress passed another law in May of 1866 — one that ended the practice of allowing the printing of paper currency worth less than 10 cents. If you really want one, you can often find them on eBay for well under $50.

Bonus fact: The Confederacy also had currency problems of its own during the Civil War. Their issues, though, were in large part due to a prankster named Samuel C. Upham. Upham, a Union loyalist, obtained some Confederate cash and began printing his own counterfeits as novelty items — and, to his credit, added a small line at the bottom that spelled out that his rebel dollars were fake (as seen here). But smugglers didn’t care; they purchased Upham’s fakes at a fraction of the face value and simply cut the disclaimer off. The South was flooded with fake notes as a result. The impact? Per Wikipedia’s editors, “Some modern analyses estimate his fake Confederate money amounted to between .93% and 2.78% of the Confederacy’s total money supply.”

From the Archives: Why the $1 Bill Doesn’t Change: It has more to do with Clark Bars than Spencer M. Clark.