You Actually Win Friends With Dirty Salad?

Pictured above is a salad in a wooden bowl, taken from Martha Stewart’s website. (I hope she doesn’t mind.) There’s nothing particularly notable about the salad or the bowl (with apologies to Ms. Stewart); salad is often served in wooden bowls like that, and the recipe, if you click through, is for a “classic Caeser salad,” which is to say, a perfectly good salad choice but not something exceptionally interesting.

But if you were serving salad out of a salad bowl like this say, in the 1940s, there’s a good chance it would differ from the one above — especially if you found yourself at a high-class affair. The bowl may have been dirty. And intentionally so.

And most likely, it’s because a bunch of food snobs fell for a joke.

The general rule when it comes to food prep is simple: wash your dishes and cookware after using it. There are definitely exceptions — you don’t want to use soap to clean a cast-iron pan — but those are few and far between. George Rector, a restauranteur and food writer in the 1920sand 1930s, certainly new that; if you visited one of his restaurants, you almost certainly ate off of dishes that were washed before your food was placed on it, and your food was likely prepared on surfaces that were similarly clean. But on September 5, 1936, Rector said otherwise.

That day, the Saturday Evening Post ran an essay by Rector titled “Salad Daze.” It’s not online, unfortunately, but if you have a copy in your attic, you’ll find that Rector uses his column inches to assert that the best way to make a great salad is to serve it from a plain wood bowl, rubbed down with a clove of garlic before each use. Other than that, though, you were to never, ever, wash that bowl. The reason? The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette excerpted the core of the argument:

“Wood, you see,” he wrote, “is absorbent, and after you’ve been rubbing your bowl with garlic and anointing it with oil for some years, it will have acquired the patina of a Corinthian bronze and the personality of a 100-year-old brandy.”

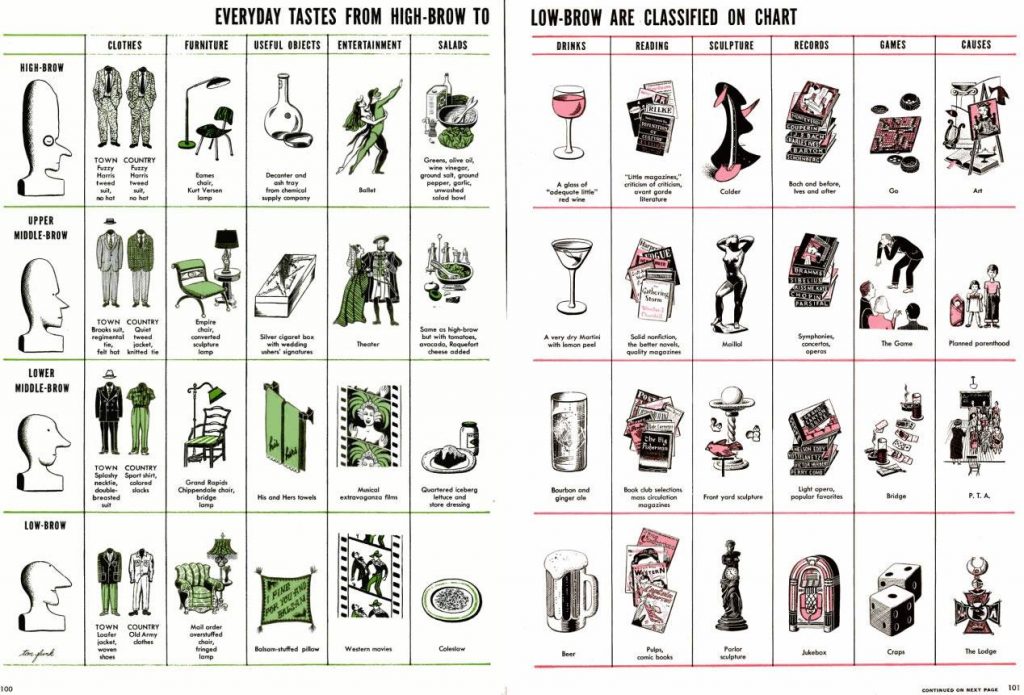

Of course, that’s a really bad idea — the wood definitely absorbs stuff, but a lot of it isn’t good for you if you let it sit around for “some years.” Rector, according to the Food History Almanac, knew this; he was waiting “with his tongue firmly in his cheek.” But like any great sarcasm, many were fooled — and for a long time. In 1949 — more than a decade after Rector made this ridiculous claim — Life Magazine ran the infographic below, titled “Everyday Tastes from High-Brow to Low-Brow are Classified on Chart.”

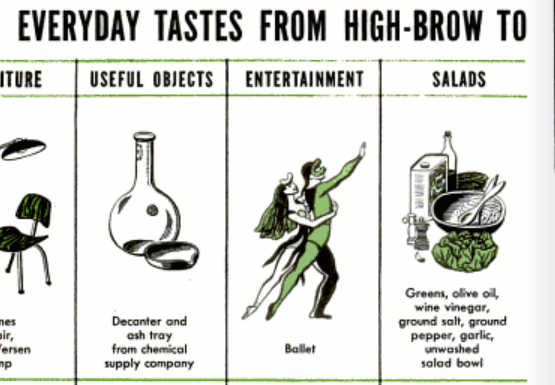

That’s hard to see because it’s so small, so let’s zoom in on what the high-brow crowd have in their “salads” column.

Greens? That makes sense. Olive oil and wine vinegar? Still good today, although you’ll find that everywhere. Ground salt, pepper? Ok. Garlic? Sure. And… an unwashed salad bowl. Rector’s joke had become fact. As the Los Angeles Times reported, the myth that “by patiently leaving your salad bowl unwashed, you could create a gourmet masterpiece at home” persisted, “so for a generation, Americans tossed salads in smelly bowls in the faith that they were steadily approaching perfection.” In the process, they were also likely poisoning their guests with rancid lettuce contaminated by whatever was lying in wait between the woodgrains.

The trend thankfully disappeared by the mid-1960s, driven in part by other food writers pointing out how ridiculous it is to serve salad out of an unwashed bowl.

Bonus fact: Caeser salads aren’t named for Julius (or even Augustus) Caeser — at least not directly. It was invented by Caesar Cardin, an Italian chef, in 1924, working out of a restaurant in Mexico to avoid Prohibition’s restrictions. As the story goes — and the details are questionable — a lot of American diners showed up at his hotel and restaurant on the 4th of July, looking to celebrate with both dinner and some drinks. He ran out of salad ingredients and, using what he had on hand, came up with the idea on the spot. He brought the “recipe” back to his Hollywood-based restaurant and it became a popular lunch option.

From the Archives: Oil Baron: The story of a salad oil maven.