Bound by the Details

Throughout the 20th century, warfare was greatly aided by the use of intelligence networks. In almost every conflict, each belligerent had spies throughout the world, trying to figure out the opposition’s next moves and long-term plans. Such spy missions came with extraordinary risk, though — capture would almost certainly lead to a loss of freedom, perhaps torture, and often death. And the better a captured spy was in gathering intelligence, the less likely he or she would be returned home. Spies, therefore, needed to be meticulously trained and disguised — and provided with fool-proof documentation as to their fictitious origin.

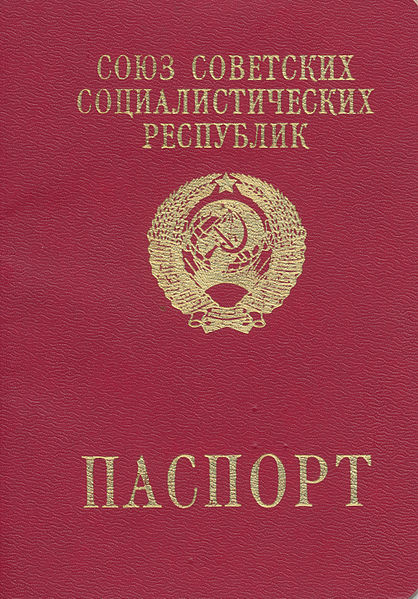

In other words, a spy needed a perfect passport — down to the staples.

This proved difficult. During World War II, the German spy network hailed from two main agencies, the Abwehr and the SD. The two agencies were competitive with one another but had different specialities, so when it came to creating fraudulent passports, they worked together. Working off expired passports from foreign travelers, the SD craftsmen tried and succeeded in creating paper stock which matched the type used in the Soviet documents. And the Abwehr, according to the book “Agent Garbo: The Brilliant, Eccentric Secret Agent Who Tricked Hitler and Saved D-Day,” employed nearly two dozen master engravers and artists who, with much practice, could replicate the rest of the passport’s features. If you were a German spy entrusted with infiltrating the Soviet Union, you didn’t have to worry about your paperwork raising any alarms.

Except for one little problem — a problem which wouldn’t reveal itself for weeks after you were given your shiny new passport. The official, real Soviet passports cut costs by using lower quality staples — staples which were prone to rusting, and over time, left a red mark on the paper. German staples, on the other hand, per “Agent Garbo,” used “nonrusting chromium-plated wire” which did not rust, and therefore, showed no red marks as the passport aged. Apparently, only one German spy’s true identity was discovered this way, but as the above-mentioned book noted, he almost certainly met a terrible fate.

While the Germans were somehow able to suss out the rusted staple detail — there are no other reports of their spies falling prey to the error — the error did not spread to other nations’ intelligence communities. In 2001, a Chicago Tribune reporter visited the secretive KGB museum in Moscow and found some Soviet passports on display. Some were real, used by Soviet citizens, and others were counterfeit, typically used by American spies. The counterfeit ones were easily recognizable if you knew to look at the bindings — they used stainless steel staples and therefore hadn’t rusted, while the genuine ones were marked by telltale corrosion. According to the former KGB official interviewed by the Tribune, “hundreds of American agents were caught, because their phony passports had the wrong staples.”

Bonus Fact: In 2008, a British woman named Laura Matthews legally adopted a new middle name — “Skywalker.” For the first few years, there was no problem, and L. Skywalker Matthews was a regular citizen like any other. Until, that is, she went to renew her passport. As the BBC reported, she tried to sign her name as “L. Skywalker” but the government disallowed the signature, despite the fact that it was her legal name and, for example, on her driver’s license. The reason: the passport office saw the Skywalker name as a trademark, violating the Star Wars franchise’s rights.

From the Archives: North Korea’s Mickey Mouse Club: How a passport changed the future of North Korea.

Related: “Agent Garbo” by Stephen Talty. 4.4 stars on over 120 reviews.