China’s Temporary Love Affair with the Mango

Mangoes — the fruit — are indigenous to South Asia, and about 40% of the world’s mango production comes from India. The fruit isn’t native to China but it’s become popular there; about 10% of all mangoes are grown there. But for a while, mangoes were more than just a cash crop for the Chinese — they were a symbol of patriotism.

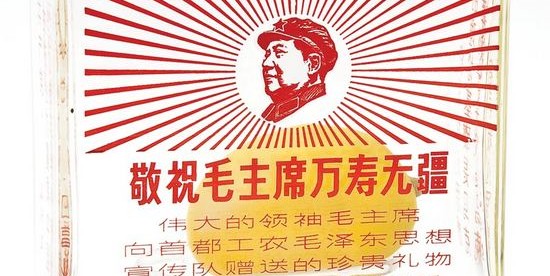

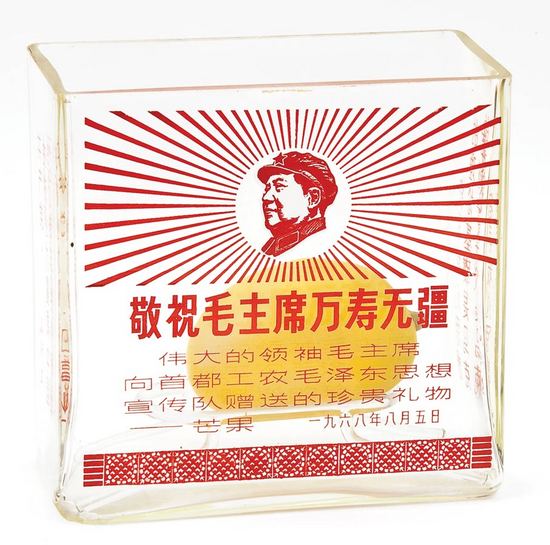

Pictured above is a mango — a well-preserved one at that. The fruit is that yellow orb in the middle of what looks like a glass case. The case is adorned with red lettering, some designs, and most importantly, a profile of Mao Zedong. The entire contraption is called a mango reliquary –it is, effectively, a shrine to the mango. Why?

Let’s start with a translation of the reliquary’s text (via here): “Respect and Wishes to Chairman Mao for a Long Life, Commemorate Great Leader Chairman Mao who gave this cherished gift – Mango – to Capital Workers Peasant Mao Tse-tung Thought Propaganda Team.” That’s not terribly clear — it loses something in translation, most likely — so let’s keep going.

In 1966, Mao began his Cultural Revolution, a purge of the non-Communist aspects of Chinese society. That required an army of sorts, so he tapped into the youth of the nation — students — and created the Red Guard, a paramilitary group whose members were fanatics and often blindly loyal to Mao. But, as Wikipedia notes, that loyalty was often subject to interpretation, which resulted in chaos and violence:

Excited youths took inspiration from Mao’s often vague pronouncements, generally believing the sanctity of his words and making serious efforts to figure out what they meant. Factions quickly formed based on individual interpretations of Mao’s statements. All groups pledged loyalty to Mao and claimed to have his best interests in mind, yet they continually engaged in verbal and physical skirmishes all throughout the Cultural Revolution.

Mao needed a way to stop this factionalization, so, per Slate, “Mao asked 30,000 Beijing factory workers to act as peacekeepers.” Many died in this effort, but they were ultimately mostly successful. These factory workers called themselves “The Worker-Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team” or some variant thereof. And just prior to one of their major victories, Mao met with diplomats from Pakistan — a place from which mangoes originally came. The diplomats gifted Mao a crate of about 40 mangoes, which he in turn re-gifted to the “Thought Propaganda Team,” likely not thinking much of it.

The workers thought otherwise. As Freda Murck, an art historian, told the BBC: “No one in northern China at that point knew what mangoes were. So the workers stayed up all night looking at them, smelling them, caressing them, wondering what this magical fruit was.” To them, the mangoes weren’t a snack or dessert. They were exalted to the level of something worthy of worship. The forty mangoes were sealed in wax and put on display in factories throughout the region, a symbol of the workers’ value in the eyes of their Chairman.

And then, the mania spread. The Telegraph explains:

Plastic, wax and papier mache facsimile mangoes were sent out on special lorries to tour the provinces, while enamel mugs, washbasins and plates were decorated with mangoes. Fake mangoes in glass cases were handed out to thousands of workers in Beijing to display in their homes.

[ . . . ]

One dentist in a small village, who dared to compare a touring mango to a sweet potato was put on trial for malicious slander and executed.

But ultimately, a mango is just a fruit. The mango madness was — for reasons unclear — short lived. About a year or two after the original gift of forty mangoes, the fruit’s cultural luster lost its significance — leaving a lot of odd relics behind.

Bonus fact: Harvesting mangoes comes at a cost — itchiness. One of the natural oils of a mango tree contains a compound called urushiol, which is the same allergen found in poison ivy, poison sumac, and poison oak. (The allergen is in the fruit’s skin but not the fruit itself, so eating peeled mangoes won’t irritate your throat.)

From the Archives: To Kill a Sparrow: One of Mao’s many bad ideas.

Related: “Mao: The Unknown Story,” an 800+ page dive into his life and misdeeds which pulls no punches. Four stars on more than 450 reviews.