Kidnapped

In 1912, Lessie and Percy Dunbar took their two sons, Bobby and Alonzo, on a fishing trip into the swamplands of Louisiana. Bobby, then age 4, disappeared. The disappearance garnered national attention — a prominent Louisiana newspaper at the time called the suspected kidnapping the crime of the century (albeit in a century of a mere 12 years).

The search for Bobby Dunbar was extensive, especially by the standards of the era. The family’s home town offered a $1,000 reward for his return (over $20,000 in today’s dollars), no questions asked. The family mailed postcards describing their child, with coverage throughout the southeast and as far west as central Texas. The lake his family was visiting was systematically blown up — literally dynamited — in hopes of jostling loose the boy’s body, or at least clearing out the alligators who frequented the body of water. (Or perhaps it was due to a myth, mentioned in Huckleberry Finn and explained here, which incorrectly posited that a similar explosion would cause a corpse’s gall bladder to erupt, thereby getting the lifeless body to float to the top of the body of water imprisoning it.) These same alligators and others in the area were killed and flipped over so that the soft undersides of their bellies could be cut open, in hopes of finding young Bobby’s body. But these efforts proved futile.

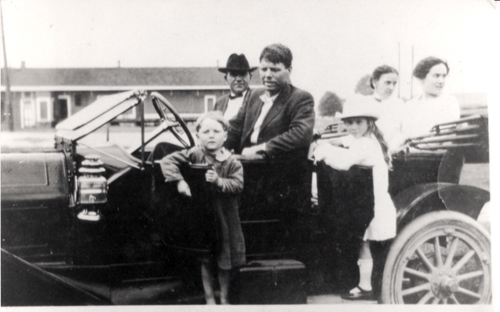

Eight months later, a travelling piano tuner by the name of William Cantwell Walters was stopped by authorities while in Mississippi. He had in tow a travelling partner — a young child, roughly age 5 (pictured above), and meeting Bobby Dunbar’s description. Walters claimed that the boy was C. Bruce Anderson, the son of Julie Anderson, a single mother (which at the time, was a big deal) who worked for Walters — and that Ms. Anderson had given Walters permission to bring the boy with him on his trip. Nevertheless, the Dunbars were brought to the young boy and — depending on what account you believe — either instantly recognized him as their dear Bobby or, a day later, made the positive ID. (After all, a child can grow a lot at that young age.) Either way, Bobby Dunbar was found, and he was coming home, to much fanfare. He’d never see Walters or Anderson again.

Walters was accused of kidnapping, a charge he staunchly denied. Anderson, per newspaper reports, was asked to pick “her son” out of a lineup of five similarly aged children and was unable to — which not only harmed her credibility, but buttressed allegations that she was of questionable morals, having given birth to two other children out of wedlock as well (both of which had died). With Anderson not much of a witness, Walters was convicted of kidnapping. He’d serve two years in prison for his crime, but won an appeal which required he be tried anew. The prosecution, citing very high costs, declined to retry him, and Walters was set free. Anderson, for her part, eventually married and started a new family.

Neither Walters nor Anderson ever confessed to making up the tale of Bruce Anderson. Walters, to his death, maintained his innocence. Anderson continued her belief that she, and not the Dunbars, was the victim, and that her boy Bruce was kidnapped by them (and not the other way around).

They were probably right.

In 2004, Bob Dunbar, Jr. — the son of the boy pictured above — consented to DNA testing. His DNA was compared to that of Alonzo Dunbar, Jr. — the son of Bobby’s younger brother — and the test conclusively determined that the two were not related. Most likely, the boy taken from Julie Anderson was, indeed, her son Bruce. And almost certainly, William Cantwell Walters was not a kidnapper.

The whereabouts and fate of the real Bobby Dunbar were never determined.

Bonus fact: In 1973, in the Canary Islands, a mother gave birth to twin daughters. Due to a hospital error (and unbeknownst to her), she came home with only one of the twins and, in the other’s place, a different baby girl. The mom raised them as if they were the twins she believed them to be, while the true parents of the switched baby raised the other biological twin as their own. Twenty-eight years later, this now-singleton twin came to a store in a shopping center where her biological twin sister worked, and was greeted by an employee who mistook her for that twin. The employee set up a meeting between the two, and later, DNA tests proved that the two women, separated but now reunited, were indeed biological twins.

From the Archives: Groom Kidnapping: Exactly what it sounds like.

Related: “Mistaken Identity: Two Families, One Survivor, Unwavering Hope” by Don Van Ryn. From the publisher: “In a widely reported incident in 2006, Laura Van Ryn and Whitney Cerak, students at an evangelical college in Indiana, and their families were victims of a ghastly mistake: the wrong girl was identified as the survivor of a car crash that claimed multiple lives. Only after five weeks, when the girl emerged from a coma, was the error discovered. The families and the survivor, Whitney, record their experiences in this heavily Christian account.” 147 reviews, 4.5 stars on average, with most of the 1- and 2-star comments warning that if you aren’t a religious Christian, the book is not right for you. Available on Kindle.

Leave a comment