The American Civil War of World War II

If you were alive during World War II, you were probably getting a lot of your news from the daily newspaper. Reports from both the European and Pacific fronts brought back news of victories and losses, almost all of which were punctuated with deaths of American soldiers, sailors, and marines. But if you were paying attention in late June or early July of 1943, there’s one American casualty you likely missed — the death of William Crossland, a private in the 1511th Quartermaster Truck regiment in the U.S. Army Air Force. And the reason why you’d have missed it is, most likely, shame.

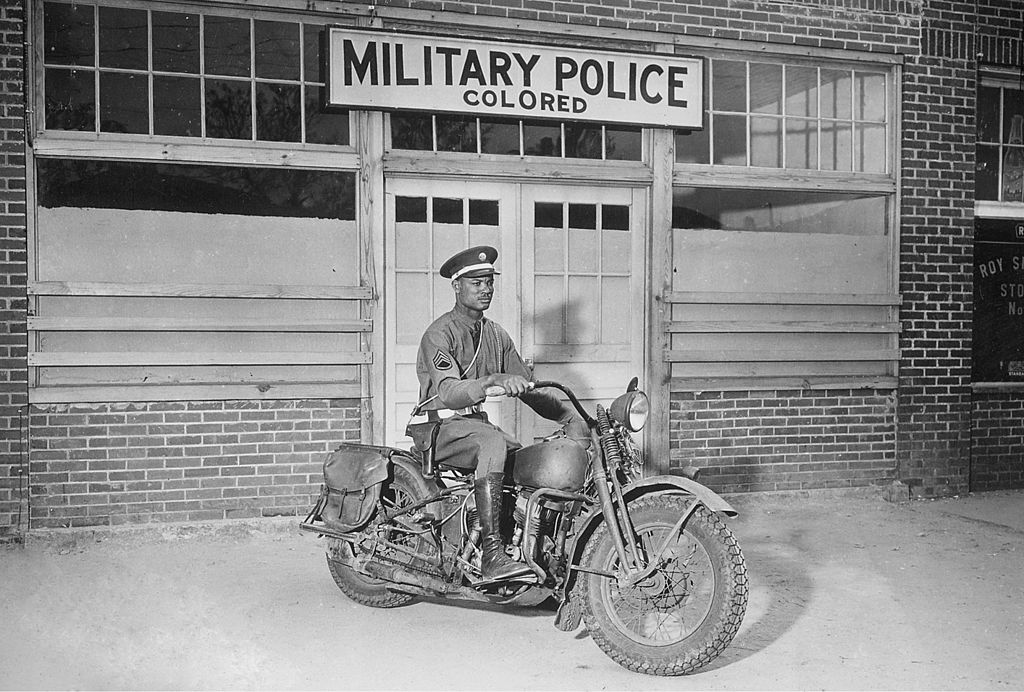

For much of the 20th century, racial segregation was the norm — and the law — throughout much of the United States. One would have hoped that those policies would not carry into the military, but as seen above, they most definitely did. And this applied overseas as well. Most regiments were de facto segregated, with many black soldiers serving in all-black or almost all-black regiments. Most black soldiers were given lesser, logistical roles such as cooks, gravediggers, and quartermasters, away from the field of combat. It was rare to find black officers; in the case of the 1511th Quartermaster Truck regiment, almost all of the enlisted men were black, but all but one of the officers directing them was white.

In the summer of 1943, the 1511th was stationed at Bamber Bridge, a village in the UK village of Lancashire, England. The white American officers tried to segregate out the black soldiers even while abroad — but found themselves in a town that wasn’t willing to play along. According to the Lancashire Evening Post, “the people of Bamber Bridge, on the whole, supported the black troops, and when American commanders on, what was considered a knee-jerk reaction, demanded a colour bar in the town, many of the pubs reportedly posted ‘Black Troops Only’ signs on their doors.” With racial tensions high — back in the United States, a racism-sparked riot in Detroit claimed 34 lives that week — “this was probably seen as the blue touch paper to a potential firecracker and all that was required to set it off was a match,” continued the Evening Post. And on June 24th came that spark.

That evening, some of the black soldiers from the 1511th were at a local pub called Ye Olde Hob Inn, drinking with some similarly off-duty British soldiers and some British civilians. When last call was announced, though, some members of the 151tth (and likely others) carried on, continuing to ask for drinks. The bar staff refused and American Military Police (MPs) passing by took notice — and they weren’t pleased. Trying to get served after hours probably wasn’t within their jurisdiction, but the MPs nevertheless took action. They noticed that one of the American soldiers was improperly dressed and lacked a pass to take leave for the evening, and they went to arrest him. According to another Evening Post article, this attempted arrest “result[ed] in a backlash from other drinkers,” including the British patrons. But the MPs were undeterred — at first. One of the soldiers from the 1511th threw a beer bottle at an MP, setting off a skirmish between white and black Americans. The British patrons sided with the black troops, and the MPs retreated.

They returned shortly thereafter with reinforcements — and things got worse. War History Online explains what happened next:

Once again an argument ensued, and this time it boiled over into a more serious battle, involving black servicemen and white Britons against the white MPs, in which a shot was fired and an African American serviceman was hit in the neck.

The shooting of the serviceman temporarily quelled the riot, but when a truckload of MPs arrived at the camp later that night armed with a machine gun, panic rippled through the African American troops, who thought that they were going to be shot.

The panicking troops raided the camp’s gun room, taking around two-thirds of the rifles and arming themselves. A large group of the now-armed servicemen then left the camp, and in the darkness fought running battles with the MPs through the town, with each side firing occasional shots at the other.

One African American serviceman, Private William Crossland, did not survive. When the violence finally subsided at around 4 AM the next morning, seven people had been injured. Due to the darkness, few shots had been fired and most had not hit their targets.

Stateside, the violence went mostly unreported, with only some perfunctory reports of a fight making a few papers; Private Crossland’s death, in most cases, was simply omitted from the news. At first, the imbroglio was captioned “the Mutiny of Bamber Bridge,” and resulted in the court-martial of 32 black soldiers, all of whom were found guilty of various crimes. Those sentences were quickly reduced, however; as a Wikipedia editor summarized the aftermath, “with the poor leadership and use of racial slurs by MPs considered mitigating factors.” The MP ranks which oversaw the 1511th were racially integrated aftward, in an effort to help prevent bigotry from ruling the day in the future, and the commanding general, Ira C. Eaker, rid his ranks of “inexperienced and racist officers” again per Wikipedia.

More broadly, racial segregation remained the official policy of the U.S. Army through the war and beyond. “On July 26, 1948,” reports PBS, “President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which ordered the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces.” Today, perhaps as a reflection on the shame of the events above, the violence is rarely referred to as a mutiny; it is, instead, called “the Battle of Bamber Bridge.”

Bonus fact: Segregation at the time resulted in extra bathrooms at the Pentagon, which was built during World War II. Designers, not sure whether to follow Virginia law (which required segregated bathrooms) or President Roosevelt’s executive order barring discrimination based on race, built four sets of bathrooms wherever two would otherwise do. As Snopes relays, “Roosevelt and [adviser Harry] Hopkins came over to see the building for themselves on Saturday, May 2 [1942]. The president told Renshaw he was delighted with the progress. Touring the interior, however, Roosevelt and Hopkins were puzzled to find four large washrooms on each of the main hallways leading from the outer ring of the building to the inner, according to an account related by historian Constance M. Green in Washington, a History of the Capital, 1800-1950. The president, ‘upon inquiring the reason for such prodigality of lavatory space,’ was informed that this was to comply with Virginia segregation laws requiring separate facilities.”

From the Archives: A City Fit for a King: More than twenty years after the Battle of Bamber Bridge, a Nobel Prize becomes a flashpoint for racism — and for change.