The Day Care Fine that Backfired

Blue Man Group, if you’re unfamiliar with them, is an eclectic performance art troupe. Their shows are, well . . . the shows are hard to describe because they’re weird by design. It’s a mix of sound, colors, lighting, and more which don’t combine so much to tell a story, but rather to play with the senses and expectation of the audience. This isn’t intended to be an endorsement or recommendation of their shows (although I really did like the one I went to, years ago). But if you do decide to check it out, here are some words of advice:

Don’t show up late. They don’t take kindly to it.

(If you’ve seen a Blue Man show, you know why already. If you haven’t, I’m about to ruin this part for you, kind of — it’s not quite the same as experiencing it in person. Regardless, this your warning. The video clip below gives away the gag. Sorry.)

Blue Man Group, if you’re unfamiliar with them, is an eclectic performance art troupe. Their shows are, well . . . the shows are hard to describe because they’re weird by design. It’s a mix of sound, colors, lighting, and more which don’t combine so much to tell a story, but rather to play with the senses and expectation of the audience. This isn’t intended to be an endorsement or recommendation of their shows (although I really did like the one I went to, years ago). But if you do decide to check it out, here are some words of advice:

Don’t show up late. They don’t take kindly to it.

(If you’ve seen a Blue Man show, you know why already. If you haven’t, I’m about to ruin this part for you, kind of — it’s not quite the same as experiencing it in person. Regardless is your warning. The video clip below gives away the gag. Sorry.)

How the Blue Man Group reacts to tardiness can be fairly summarized as a grossly exaggerated objection to a pretty minor violation of social norms — that’s why it gets a reaction from the crowd. As a rule, you probably shouldn’t be late to things — it’s a bit selfish, right? But we all understand that delays aren’t often avoidable so we tend to give one another a pass, unless it becomes habitual, in which case, uncomfortable conversations may be on the agenda — or we impose fines on the latecomer. That latter example is what you see in libraries when people fail to return books on time, but that’s not quite analogous to the Blue Man Group situation.

A better one: day-cares which fine parents and caregivers who show up late for pickup.

In 2000, two researchers — Uri Gneezy of University of California at San Diego and Aldo Rustichini of the University of Minnesota — posed the following question:

Suppose you are the manager of a day-care center for young children. The center is scheduled to operate every day until four in the afternoon, when the parents are supposed to come and collect their children. Quite frequently, however, parents arrive late, and force you to stay after working hours. You have considered a few alternatives in order to reduce the frequency of this behavior. A natural option is to introduce a fine: every time a parent comes late, she will have to pay a fine. Will that reduce the number of parents who come late?

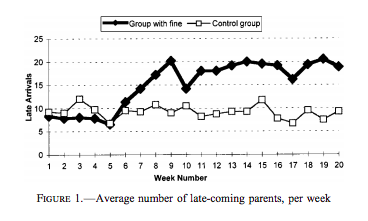

At first blush, you’d assume that yes, it would reduce latecomers. But why guess? Gneezy and Rustichini, working with a day-care provider in the Israeli town of Haifa, put it to the test. For four weeks, they monitored the pick-up times of ten different classrooms, recording how many parents arrived after 4 PM. Then, before the fifth week, a notice went out to the parents of six of the ten classes: parents would be fined 10 Israeli shekels per child — about $3 — if the child was picked up more than ten minutes later. (The other four classes were kept as-is, as a control group.)

It didn’t reduce the number of latecomers. In fact, it increased it. Here’s the graph from the paper, and it’s pretty clear: in week five, late pickups increased, and then kept increasing for a few more weeks until it hit a plateau (save for a one-week dip).

Weird, right? Behavioral economics professor Dan Ariely discussed the study on NPR and offered an explanation:

Before the fine was introduced, the teachers and parents had a social contract, with social norms about being late. Thus, if parents were late — as they occasionally were — they felt guilty about it — and their guilt compelled them to be more prompt in picking up their kids in the future. [ . . . ] But once the fine was imposed, the day care center had inadvertently replaced the social norms with market norms.

Basically, the fine removed the guilt and replaced it with a price tag. And in this case, the price tag was probably too low — for many, the $3 late fee was worth it. Maybe a $20 fine would have different results, but the researchers didn’t end up testing that.

They did, however, test one other thing: what happens when the fine goes away? In week 17 of the trial, Gneezy and Rustichini removed the fine, sending parents a note home to that effect. And you see a dip in latecomers — but only temporarily. Once the day-care centers put a price on lateness, the guilt-trip genie was out of the bottle. Parents who were willing to pay for the privilege of showing up more than 10 minutes late had no problems doing so — even after they no longer had to fork over their three bucks.

So, if you’re going to design a fine, beware — it can backfire. As Ariely summarizes, “once the bloom is off the rose — once a social norm is trumped by a market norm — it will rarely return.”

Bonus fact: In 1939, a grad student named George Dantzig was late for a statistics class at the University of California at Berkeley, so he did what any other latecomer would do — he quietly copied the assignment off the chalkboard and called no attention to himself otherwise. The two assigned problems proved difficult but not impossible; Dantzig, after a few days of work, puzzled out a solution to each. His professor was taken by surprise — the problems weren’t an assignment. Rather, as the Washington Post describes, they were “two of the most famous unsolved problems in statistics,” and the professor had simply shared them as an example of the work still yet to be done in the field. And Dantzig had managed to solve them both anyway. (Unsurprisingly, Dantzig went on to have a career as a storied mathematician.)

From the Archives: Life in the Fast Lane: How to get yourself a $100,000 speeding ticket.