The Pothole Vigilante

The Canadian town of Stellarton is located in the northern part of Nova Scotia. It’s an old coal-mining town; its population peaked in the 1950s at about 5,500 residents and, for the most part, has fallen ever since. It’s hardly a ghost town, though. With just over 4,000 residents, Stellarton isn’t all that different than most other small towns in the area.

And like any other small town, especially one where roads get wet and icy, there are potholes. And there are people whose job it is to fix those potholes. Those people are important — take my word for it. (Seriously. Two years ago, I hit a pothole while driving home and cracked a wheel. No, I didn’t just bust a tire, which sucks — I cracked the wheel itself. Stupid pothole cost me a lot of money.) And if you’re in Stellarton, you can go to the town website to report a pothole, or at least to get the name, address, and phone number of the person responsible for fixing it.

Or you can just buy some guy named John some weed.

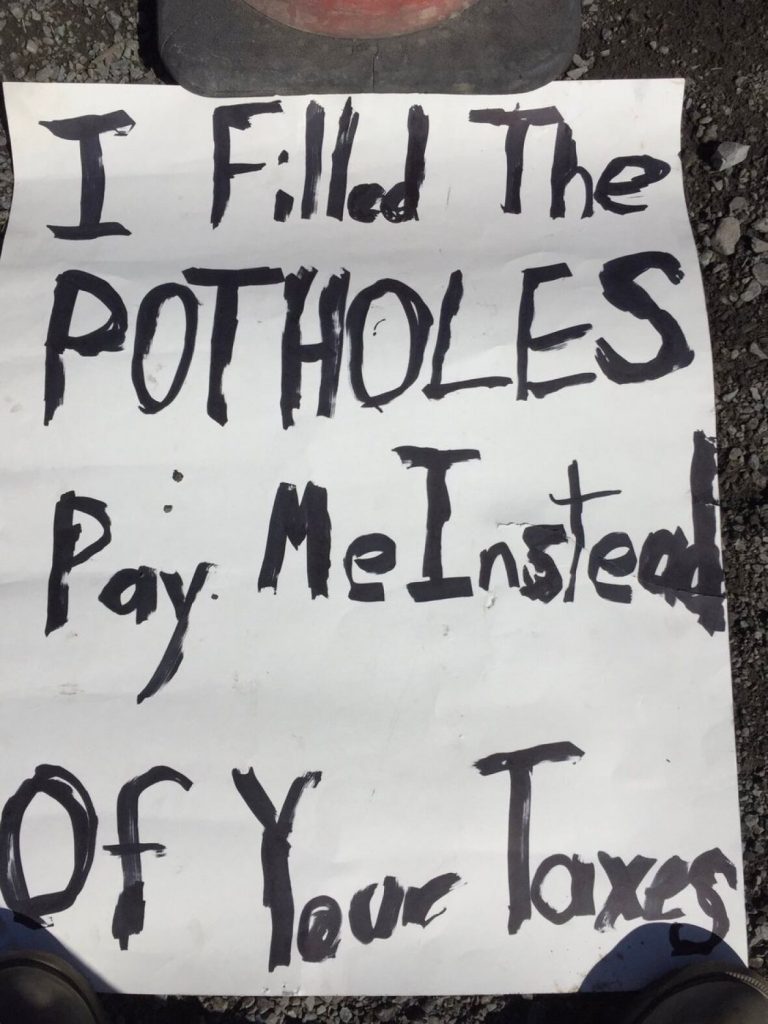

In March of 2019, a then-22-year-old man named John McCue decided that he had enough of Stellarton’s unfilled potholes. Despite not being the official pothole filler in Stellarton — and certainly not a town employee — McCue saw an opportunity to do the work anyway, and to ask for tips. As New Glasgow News reported, McCue, “using a snow shovel . . . spent at least two hours taking gravel out of the shoulder of the road and tossing it onto the potholes from a distance.” Cars would roll over the filled-in gaps, packing the gravel and dirt more tightly, reducing the bumps for the next motorist. For McCue, this wasn’t to his direct benefit either; at the time, he didn’t even own a car. It was, however, a way to make ends meet. A self-described busker by trade, McCue told the media that he “busked for probably four or five years. Just like hula hooping, juggling, balance board, I do all that kind of stuff for crowds at bars to just get tip money and I actually find this very similar.” He outfitted his crudely-filled potholes with a cone and the sign, seen below.

While tossing dirt into a hole is a crude and temporary solution, in McCue’s eyes, it was an effective one. And motorists agreed. He told the CBC just shortly after a pothole-filling afternoon, “I’m getting definitely a lot of tips — I had a couple of people give me some joints, too, which is pretty nice.”

But not everyone was a fan, the local authorities chief among them. A spokesperson for the Nova Scotia Department of Transportation and Infrastructure Renewal told Global News that road repair shouldn’t be a DIY project. Per the spokesperson, the Department “understands the frustration that potholes cause [ . . . ] but we strongly encourage motorists to contact [us] rather than taking matters into their own hands,” as doing so can be “very dangerous without the proper safety measures in place.” And they also threatened to take legal action against McCue for his efforts; he told the CBC that the town police, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and DOT officials all came by and warned him that if he kept up the unauthorized repairs, he’d risk being arrested.

McCue didn’t seem to mind, though. As he further told the CBC, he wasn’t long for Stellarton anyway. He was “starting a new job out west in two months and said he would like to use some of the money he’s made filling in the potholes toward living expenses, like food.” Oh, and in his own words, McCue also admitted that he was “probably going to buy some weed with it, not going to lie.”

Bonus fact: Maybe McCue should have found a job delivering pizza? His resume would be great for Domino’s. In 2018, the pizza chain engaged in a creative marketing campaign called “Paving for Pizza,” began paving roads throughout the United States. Per Restaurant Business Online, Domino’s saw the campaign as a natural extension of their delivery and takeout brand promise: “‘Cracks, bumps, potholes and other road conditions can put good pizzas at risk after they leave the store,’ the company said in a release. ‘Now Domino’s is hoping to help smooth the ride home for our freshly made pizzas.'” And no, the police weren’t upset with Domino’s in this case; unlike McCue, Domino’s got permission from the municipalities before doing the road work.

From the Archives: Cracked Up: How teams of lawyers helped fix New York City’s sidewalks (and built a weird map in the process).